Forgotten Black history is found again through new geocaching tour in Fredericton

Long before Willie O'Ree made history as the first Black hockey player in the NHL, he was a bored altar boy carving his name into the pew at his local chapel in downtown Fredericton.

O'Ree grew up in Fredericton, and his family attended Saint Anne's Chapel of Ease, a sandstone Gothic Revival church built in 1847.

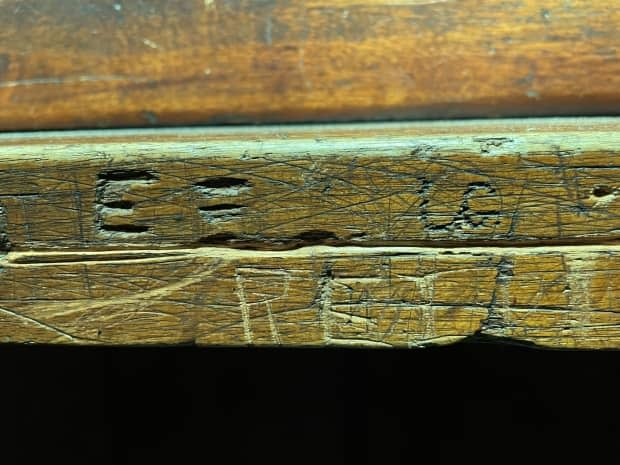

At the very back of the chapel, tucked inside a narrow butternut pew, are the attempts of a young O'Ree to mark his territory.

"You can see in a few different spots where he's tried to carve his name in. There's Ree, and E E. And you'll see W.O. throughout this area," said Graham Nickerson, pointing at the rough lines in the wood.

Nickerson is a Black loyalist historian, and the City of Fredericton's new community inclusion liaison. The O'Ree pew carving is just one stop in a larger tour Nickerson designed, highlighting little-known moments of Black history across the city and beyond.

"With Fredericton, the Black history is intertwined with white history. But most Black history no longer exists, or it's an anecdotal story, or something that's not tied to brick and mortar. So I was thinking, like, how do we represent this sort of type of history without having a monument or building to tie it to?"

He found the answer in the adventurous world of geocaching. And on July 30, Atlantic Canada's first "geotour" will be available to the public.

A hunt with adventure

So, what is geocaching?

"It is a worldwide treasure hunt, which involves lots of adventure in the outdoors, creativity, matched with technology," saidi Marion McIntyre, a director with the Capital Region Association of Geocachers.

In geocaching, the user puts a set of GPS co-ordinates into a map or geocaching app. The app then takes the user to a site where a "cache" can be found — typically a hidden box with interesting objects inside. It could simply be a logbook to let people know you were there, or it could be a small trinket that you could take with you. It could also be information about the site itself and its history.

"It often takes [people] to places, to hidden locales that you didn't know existed in your own backyard. … I guarantee I have learned a lot about Black history just having been involved in this project," McIntyre said.

If participants visit all six sites in the geotour, the city will award them a specially designed "geo-coin." The design for the coin was inspired by the halfpenny used by abolitionists in the late 18th century.

Nickerson acknowledges that for some geocachers, the attraction of the tour may be mostly about "running around and sightseeting" — or obtaining that prized geo-coin. But he also thinks the technology is useful for tracking history.

"It's about tying evidence to geographic locations, and we can watch the Black community evolve through time and space. So it works on a lot of levels."

The tour includes Fredericton's first integrated cemetery, where Black and white parishioners are buried alongside each other

According to Nickerson, St. Anne's Chapel of Ease would've been considered a welcoming space for Black parishioners when Willie O'Ree was growing up. Another historically welcoming church would've been St. Peter's Anglican Church on Woodstock Road.

"St. Peter's is an important site because it's an early Black settlement in Fredericton, and the church itself was built by the Black community, and you can see it in the stained glass window," Nickerson said.

The window, installed in 1978, depicts members of the Black community lugging timber and doing stonemasonry.

The church began construction in 1837, and was fully operational by the 1840s. Nickerson said the church is significant because it welcomed Black and white parishioners alike and was fully integrated.

"Black members were free to sit wherever they wanted. … And markedly in the graveyard, Blacks and whites were commingled in burial. The gravestones are rather ornate for that period in time. When you go to other churches where blacks are buried, it's usually fieldstones if there's any marker at all."

It was important, Nickerson said, to include a site like St. Peter's in the tour, because it challenges assumptions that people might have about the position of Black New Brunswickers in the 19th century.

"I think we're at a point in time, that we're ready to change the way the narrative has been told, in that 'Blacks have no agency' … This church and this congregation challenges that relationship. It shows Blacks in a powerful position, and as — if not as equals — as at least having a seat at the table to negotiate."

Salome's tub

Nickerson said another site of his tour that challenges assumptions about New Brunswick's Black history is Salome's Well, or Salome's Tub.

Nestled off the side of an old country road near Penniac north of Fredericton, the site is easy to miss. It's a stream of natural spring water that trickles down an old railway tie, into a giant stone tub.

"It is a water source that's currently used by locals, but back in the 19th century this would've been a watering hole for travellers up the Nashwaak [River]. They would've stopped here [and] watered their horses at Ira and Salome Gosman's farmstead."

Nickerson said the Gosmans were Black Loyalists who moved to Bridgetown, N.S., in the late 1700s, then made their way to New Brunswick. It's possible they acquired the land through a Loyalist grant, or purchased the patch of land from a white Loyalist, who would "partition off the land they didn't want, and they would sell that to either poor whites or Black loyalist settlers."

The land the Gosmans had near Penniac was located on a steep hill and not considered arable — so the natural spring water well would've been the Gosmans' main asset and source of income, Nickerson said.

"The victim narrative would be, 'Oh, the Gosmans were stuck out in Penniac, et cetera, et cetera. …' But the Gosmans used what was on this land, not traditionally farmable or grazing land, but a source of water that they could capitalize on and make a living at."

Nickerson said you can make a link between the Gosmans 200 years ago, and their descendants today. One of them is world-renowned soprano Measha Brueggergosman-Lee.

It's a bonus, Nickerson said, that the tour makes connections to Fredericton-born celebrities like Brueggergosman-Lee or Willie O'Ree. But his main goal is to get people to see New Brunswick history through a more holistic lens.

"If you can make a crack in that idea of entitlement, of 'this is mine and you're someone else,' we see ourselves as a common society with shared history, differences and similarities, and figure out how we can carry that torch forward together — that's what I aim for."

On Sunday, the Capital Region Association of Geocachers is hosting an event at King's Landing to launch the new geotour, ahead of Emancipation Day on Aug. 1. On this day in 1834, the British parliament abolished slavery, freeing about 800,000 enslaved people of African descent in Canada and other British colonies.