As Fort Worth redevelops its oldest public housing complex, residents look back fondly

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

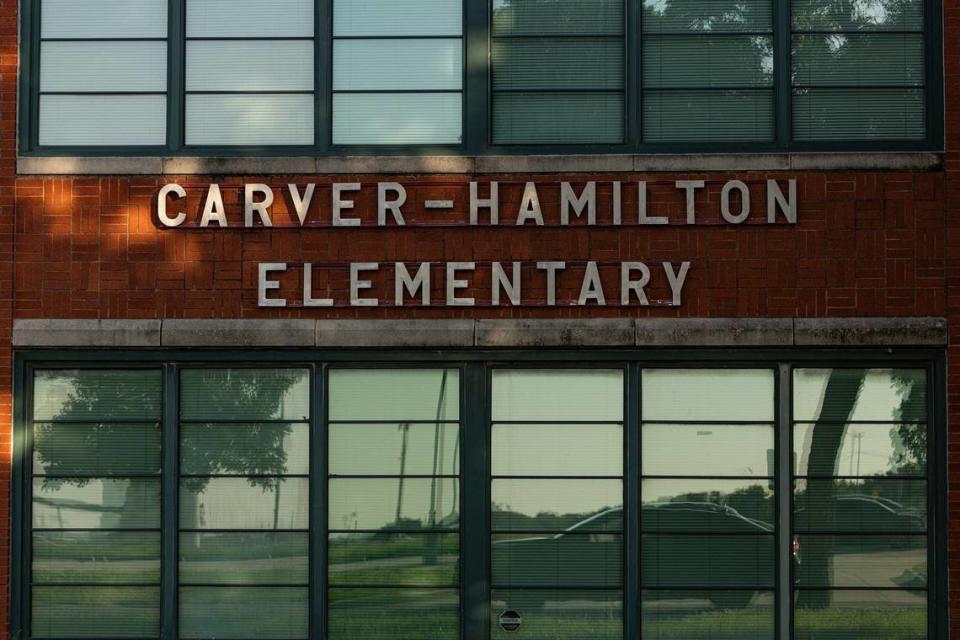

The Tuesday afternoon sun shines on the faces of chuckling men standing under the Carver-Hamilton Elementary School sign in the Butler Place public housing complex.

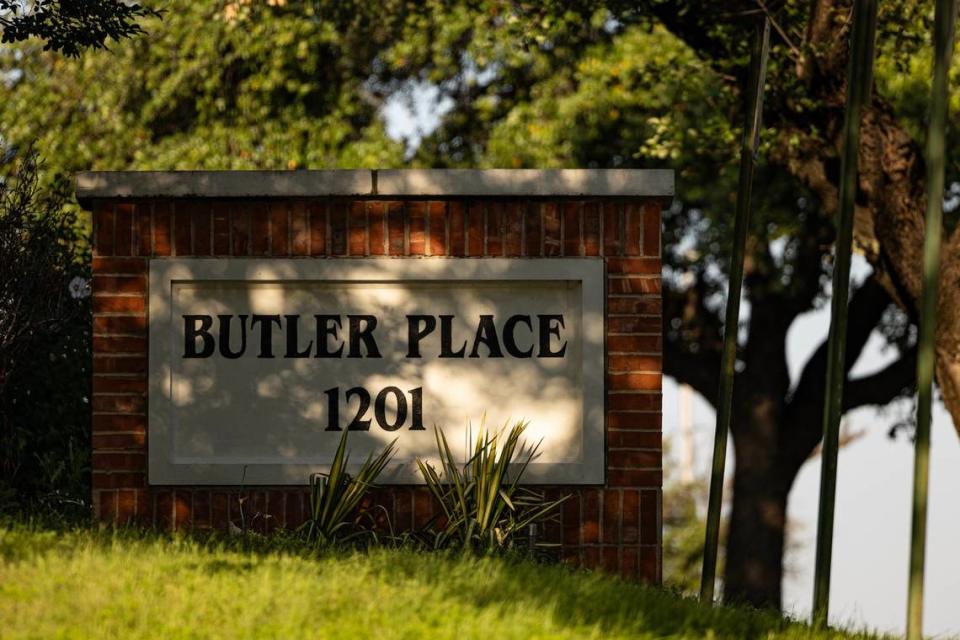

To the west, Fort Worth’s downtown skyline rises over Interstate-35W. The interstate, U.S. Highway 287 to the east and Interstate 30 to south form a triangular boundary around the red brick complex, which is now abandoned.

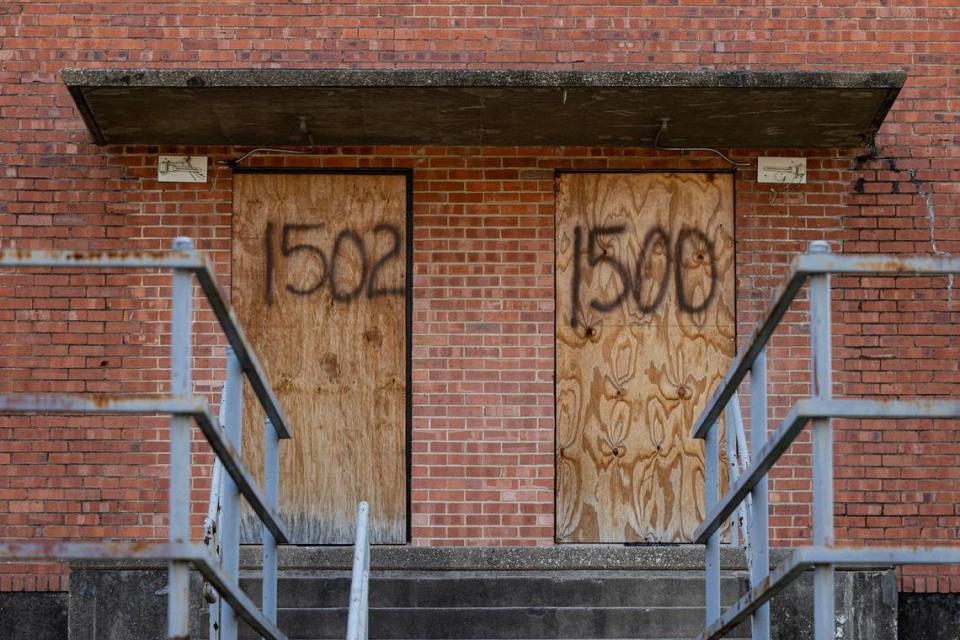

The men walk two blocks south from 13th Street to the corner of Luella Street and Stephenson Street. The buildings that were once home to hundreds of families now have boarded up windows and doors. The roofs have caved in on some of the apartments.

Donald “D Ray” Elder, 45, wears a “Brick Born” T-shirt that has a stencil in the shape of Texas with the roofs of Butler Place homes inside the graphic. He points out the empty corner lot where the building in which he used to live once stood. Four generations of his family lived in Butler Place. Elder, his mother and grandmother lived adjacent to where his great-grandmother stayed.

The projects represented freedom to Elder. When he was younger, he and his friends hoped the grass wouldn’t be cut on what they called Pork Chop Hill, going from Luella Street down to I.M. Terrell Way Circle North. They slid down the hill on pieces of cardboard, and long grass meant a better ride. Other freedoms included finding a quarter to take the bus to the mall at the former Tandy Center downtown (once the corporate headquarters for Radio Shack, formerly Tandy) or going to the neighborhood store with a list of things to get buy.

These are experiences his own children don’t necessarily understand, but they shaped who he is today. And they are tethered to Butler Place.

“We try to make sure that we don’t get too attached because we know it’s no longer open,” Elder said. “It’s not going to come back, so there is a little part of us grieving as well, the nostalgia of it. So we come back to remember.”

Whether referred to as Butler Place, The Butlers, Butler Housing, or the projects, Butler Place was a tight community for thousands of residents over nearly 80 years, until it closed in December 2020. Its history is complicated. Constructed in the Great Depression at a time of segregation, its residents lived with the stigma associated with public housing projects and suffered the brunt of societal ills such as crime, gangs and the crack epidemic of the 1980s and ‘90s.

But those things never stopped the residents of Butler Place from finding comfort and fellowship with one another and sharing a feeling of community.

“We were poor with money, but we were rich in companionship,” said Roshawn Moore, 61, who says he learned the value of the extended family formed through his neighbors as he grew up in Butler Place.

Now, many former residents hold onto their fond memories of Butler Place as they contemplate the future of property. Though pieces of it will be preserved, the housing complex is expected to largely be torn down as the land is targeted for redevelopment. What the property will be used for hasn’t been determined, but it’s seen as an attractive element to complement other development on the east edge of downtown Fort Worth, such as the expansion of the Texas A&M School of Law.

‘Mo Betta Butler’

Childhood best friends, or brothers as they call each other, Greg ‘Keke” Wilson, 54, LC Timms, 54, and Joe “Jay Smooth” Collier, 54, grew up in Butler Place in the ‘70s and ‘80s. They wore white T-shirts with their names, nicknames and the words “Mo Betta Butler” stitched on them by Wilson’s wife as they walked around the complex with Elder and other men on a recent Tuesday afternoon.

Despite the stigma it had, Timms remembers Butler Place as a family oriented community. “And everyone had love for each other and everyone looked out for one another,” he said.

Wilson, Timms and Collier played football and marbles with other kids in the neighborhood and organized relay races. In the summer, they went to Harmon Field Park, east of U.S. Highway 287, where they attended concerts and played baseball. It also was home to the now closed Bertha Collins Community Center, which offered free lunches, indoor basketball, roller skating on Thursdays for 25 cents, and other activities.

There was no air conditioning in their homes at Butler Place. Residents would position fans in their windows that blew a cool mist into their homes. It would be so hot outside, according to the men, they would pour water on the bricks to cool them down. At night they laid in bed next to a window waiting for what Timms described as a “cool project breeze.”

They all went to Carver-Hamilton Elementary School and Arlington Heights High School, where they played on the football team.

As they got older, they developed new spots to hang out like the Fort Worth Water Gardens, which Collier says was their swimming pool, and the Tandy Center, now called City Place. They remember the Glass Key Cafe, a notorious spot at 800 E. Luella St., where gambling, drugs, and homicides were frequent.

History of Butler Place

Butler Place is Fort Worth’s oldest public housing complex. It is wedged on 42 acres on the east edge of downtown.

It was one of 52 Works Progress Administration projects for low-income housing under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, designed to provide jobs during the Great Depression. It opened in the early 1940s and was named after Henry H. Butler, a Civil War veteran and the first African-American teacher in the Fort Worth school system.

In February, the city’s Historic Cultural and Landmarks Commission recognized the buildings in Butler Place at 1715-1750 Stephenson St. and 1801-1825 Stephenson St. and the nearby former Carver-Hamilton Elementary School building as Historic and Cultural Landmarks.

According to a staff report by the Historic and Cultural Landmarks Commission, the former school is associated with the African American community and the “development of increasing access to public schools for African American students.”

The staff report said Butler Place was associated with housing African American residents and the “development of social housing within Fort Worth” after the Great Depression. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

The toll of crack cocaine

The crack cocaine epidemic that hit Fort Worth — and the rest of the country — in the ‘80s took its toll at Butler Place.

Gangs such as the Crips rose in the housing complex, and drug abuse was visible to anyone walking through it.

“It flooded everywhere,” Collier said. “Crack didn’t discriminate against anyone Black, white, Asian, Mexican. Everyone was smoking that crack or you were making money if you didn’t smoke it.”

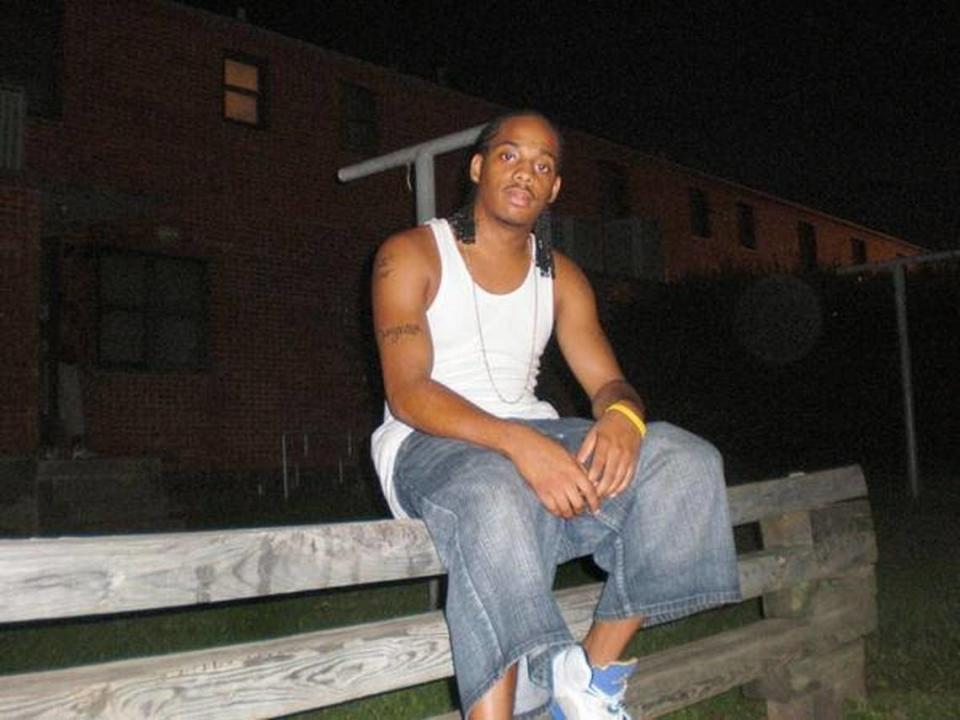

Darryl Givens, 38, remembers playing as a kid on Water Street and sitting on chairs left out on in yards and on porches. Adults shooed children away and then removed bags of crack hidden in cutouts in the chairs.

He saw small plastic bags and smoke pipes in the dirt when he played outside. Givens and other children described the men, women, and families who fell victim to drugs as “the zombies,” a reference from the 1968 movie “Night of the Living Dead.”

Only a small population of people at Butler were users, according to Givens, but it influenced people like him. He didn’t use crack, but the idea of selling it to make fast money and provide the luxury he couldn’t otherwise have was tempting, he said.

Givens, known by the nickname “Pee Wee,” said he sold marijuana in high school, wanting to feed his ego and buy the newest Jordans, but stopped when the risk became clear. He saw police knock down the doors of drug houses he had just left. One time, he said, he found himself looking down the barrel of a police officer’s gun during a drug deal on Water Street. Givens was taken to the police station but wasn’t charged. He said that was enough to get him to stop selling drugs.

Givens said his peers and the various programs at Butler Place provided perspective and grounding. Field trips to Mayfest and entrepreneurial classes Givens participated in opened his eyes to a world outside of Butler Place.

“Someone had another love for me to take me somewhere outside of my comfort zone, which is inside these housing projects, to see something I’ve never seen in my life,” Givens said.

Allisha Shedrick, 33, said most of the girls living in Butler Place, unlike the boys, weren’t interested in being outside playing sports. They participated in programs such as AIM through the Young Women’s Christian Association, which was held in an office in Butler Place. The program included games, sex education, pageant shows, and more. Girls in the program would be taken downtown with large plastic bags to shop at a pantry for food so they would have something to eat at home.

She still uses the lessons she learned at AIM today.

Unfortunately, she was among one of the last groups of children in Butler Place to participate in activities through AIM and the Boys and Girls Club, as they stopped serving Butler Place.

“I remember thinking, ‘Why take something away that is helping us; that is keeping us out of trouble, most definitely helping us to grow up and be good, decent ladies, why would they take that away?’ ” she said.

Reunion celebrates memories

On July 24, 2021, a Butler Place reunion was organized by former residents. Gary Livingston, 61, was among the organizers.

Growing up in Butler Place, he said, he and his friends never thought of themselves as different from other children. The complex provided them with humble beginnings, and their parents made sure they could live their best lives on a limited income, he said.

“There are a lot of people that came out of Butler that made a lot of astounding impact in life,” Livingston said. “As far as political, cultural leaders, pastors, professional athletes, you have just about the whole slice of life you can get in a neighborhood.”

One of the most well known residents of Butler Place was Devoyd “Dee” Jennings, the former president and CEO of the Fort Worth Metropolitan Black Chamber of Commerce, who died the day before the reunion. Jennings is considered a pillar in Fort Worth, where he helped establish Southeast Fort Worth Inc., an agency that works to develop communities on the east and southeast sides of Fort Worth, and the William Mann Jr. Community Development Corp., which gave loans to businesses in low-income areas.

Seth Turner, 63, was another organizer of the reunion. He said he knew the beauty of people in the community, their love for the housing complex, and wanted them to have a chance to tell their stories — from those making it out of Butler Place and becoming homeowners, to those who became flight attendants or worked for the government.

The reunion focused on residents who lived in Butler Place from 1965 to 1985. More than 200 people attended the event, which started with a car tour beginning at the former I.M. Terrell High School (now I.M. Terrell Academy for STEM and VPA), through Butler Place and finishing at what is now Club Rio on East Lancaster Avenue.

Residents who hadn’t seen each other in decades created excitement that felt like heaven, Turner said.

“We couldn’t even have our program because people couldn’t stop talking,” he said.

The same group of Butler Place residents hopes to have another reunion later this year, he said.

A stepping stone

As former residents talk about Butler Place, many say they would move back to the complex if they had the chance, while others saw living at the complex as a chance to save money and move on to better opportunities.

Charon Lemons, 40, thought she was trapped growing up in Butler Place, the only place she’d known since she was 3 years old. She participated in the AIM program when she was a child as she watched an increase in crime.

It all changed when she moved out of Butler Place in 2010. She still visited her grandmother nearly every day, who was still in the housing complex. Her grandmother, who was one of the last to leave Butler Place, said she would move back if she could, while Lemons said is content with moving on.

“That was our community. It was our comfort zone,” Lemons said. “But then for some people, it was a stepping stone.”

The Future of Butler Place

Similar to other aging public housing projects across the country, Butler Place eventually became too expensive to maintain to suitable standards, according to Sonya Barnette, senior vice president and deputy director of Fort Worth Housing Solutions, which owns the complex.

In addition to being antiquated, Butler Place lacked amenities such as air conditioning. It had frequent water main breaks and electric outages. The fact that it was surrounded by three highways and didn’t have easy access to services such as grocery stores were also factors in the decision to move residents out.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rental Assistance Demonstration program sought to maintain residents’ housing assistance and de-concentrate poverty by providing affordable housing throughout the city. The strategy was also designed to give residents better access to employment, grocery stores, transportation, and more.

In a process that started in 2017 and ended in December 2020, the last public housing project in Fort Worth closed.

The Butler Advisory Committee was formed in 2016 to recommend strategies to both preserve elements of Butler Place and redevelop the property.

According to city officials, the housing complex’s location is ideal for economic development on the edge of downtown.

Factors that favor its redevelopment include its proximity to a major transit hub, direct rail access to DFW Airport and a possible high speed rail line in the future. The expansion of the Fort Worth Convention Center, the planned extension of TexRail into the Medical District, and Texas A&M’s expansion downtown are major nearby projects that developers will see as valuable.

Fort Worth Housing Solutions, will take steps to preserve the historical significance of Butler Place in accordance with the National Historic Preservation Act, to include construction of an amphitheater, developing interpretive signage about the history of public housing in Fort Worth, and saving a minimum of 1,000 bricks from Butler Place buildings.

Other efforts include the Historic and Cultural Landmark designation for the former Carver-Hamilton Elementary School building adjacent to the complex. A video history and a collection of historical photos of Butler Place have already been created.

Recently, the city established the Access Butler Place Plan, led by Fort Worth Housing Solutions and the Transportation and Public Works Department, which oversees the planning, design, construction, maintenance and operation of transportation-related infrastructure. The mission is to reconnect Butler Place to downtown, improve infrastructure, and promote economic development.

‘Do something great with it’

Standing in front of what was the rental office on Luella Street, Gary Wilson takes in the scene of Butler Place today.

When Butler Place was open, children went to the rental office for activities, lunches and games. Wilson got his hair cut in a home across the street, in the 1204 building. He remembers with a laugh how he had his hair done in a jheri curl, a style popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The street Wilson grew up on, Water Street, is around the corner.

His childhood friends and younger men who also grew up in Butler Place surround him as he talks. They laugh, joke and reminisce about their childhood.

People outside Butler Place called it the projects, but for Wilson it represented a big family.

“You just hope that they do something great with it,” Wilson said. “That way you can still come back later, and walk through and say, ‘Wow, it’s beautiful.’”