Fossils found near Old Crow, Yukon, help scientists retrace steps of ancient hyena

A pair of fossilized teeth found near Old Crow, Yukon, in the 1970s sheds new light on the migration of an ancient hyena that roamed the grassy tundra of northern Yukon during the early years of the last ice age.

Yukon government paleontologist Grant Zazula suspected for years that the teeth belonged to a hyena, but it wasn't until he brought in Jack Tseng, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Buffalo and an expert on ancient predatory mammals, that he was able to confirm his suspicion.

Zazula and Tseng published their findings in a study released Tuesday in the scientific journal Open Quaternary.

"For most of the ice age, there were all these strange animals coming back and forth through the Yukon, across the Bering land bridge into North America and into Asia," Zazula said. "They leave these little hints and these little fossils, and this is one of these little hints."

Some researchers thought the hyena was one of those animals.

"But it was never really well established when that happened — or if, in fact, it actually did, because there was no physical evidence for them ever in the Yukon before."

Hyena crossing

Gwich'in elder Charlie Thomas, who worked with scientists in the 1970s, was among a group of people who discovered the fossils. They were held at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, which is where Tseng went to examine them.

Tseng identified the teeth as belonging to a genus of hyena called Chasmaporthetes, based on comparisons to a global sample of hyena fossils.

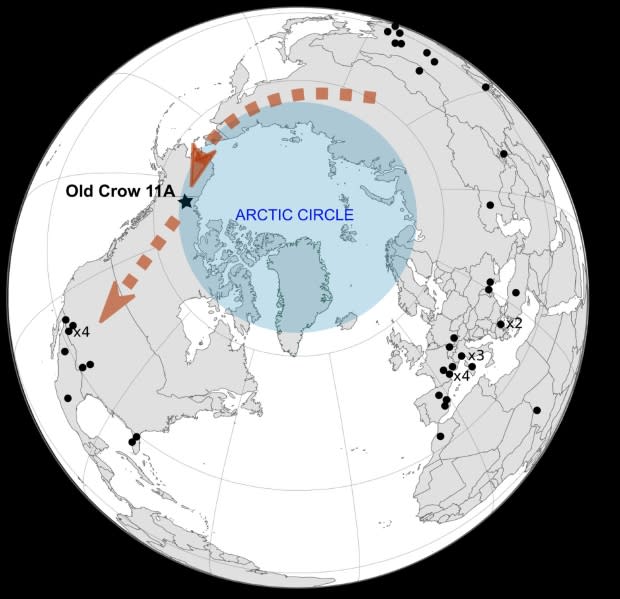

Other Chasmaporthetes fossils have been found in Mexico and in Mongolia, but never in the area between.

"There's, like, 6,000 kilometres separating these two sites," Zazula said.

Fossils of this genus had previously been found in Africa, Europe, Asia and the southern United States.

"But where and how did these animals get to North America?" Tseng said.

The teeth prove that the animal at least passed through Beringia on its way south, the researchers say.

Chasmaporthetes would have been around the same size as modern hyenas, but with longer legs to help it move more efficiently over long distances.

That's important because Chasmaporthetes would have been a hunter, in addition to scavenging for food. Zazula said the tall grasses found on the tundra at the time would have been ideal habitat for ice-age camels, caribou and mammoth that hyenas would have preyed upon.

'Bone crackers'

"They were likely very good bone crackers," Tseng said. "I mean, they're capable hunters, as well. But when they need to scavenge, they can clean out a carcass like no other predator."

At this point, scientists can still only guess at how long Chasmaporthetes stayed in what is now Yukon. While the Yukon fossils are estimated at somewhere between 850,000 and 1.4 million years old, the earliest wave of Chasmaporthetes fossils found in Mexico and the southern U.S. date to 4.75 million years ago.

"There's been over 50,000 bones of ice-age animals found in the Old Crow area in the past, and we only have two bones or two teeth of this hyena," Zazula said.

"So it's a very rare animal. It was almost like a needle in a haystack to find these animals or these fossils, so the discovery of them was quite significant."