Gene therapy offers huge potential for combating disease, doctors say

NEW YORK, May 31 (UPI) -- Researchers are engineering ways to alter genes or swap flawed ones with healthy replacements, hoping to cure diseases or enable the body to better combat them.

These breakthroughs, known as gene therapy, hold enormous potential for treating a broad range of illnesses, including AIDS, cancer, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, heart disease and sickle cell disease.

In particular, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved multiple gene therapy products for rare disorders in 2023 and 2024.

"Facilitating the development of innovative therapies to address unmet medical needs is a high priority for the FDA. The FDA views cell and gene therapy products as an excellent opportunity to expedite the delivery of potentially life-saving therapies to patients with rare diseases," an FDA spokesman said.

"We are witnessing exciting and significant progress made in this field, with growth and maturation continuing to evolve at a rapid pace since the first human gene transfer in the late 1980s. Although we can't predict future growth, we do anticipate continued scientific advancements and technical innovation in this area."

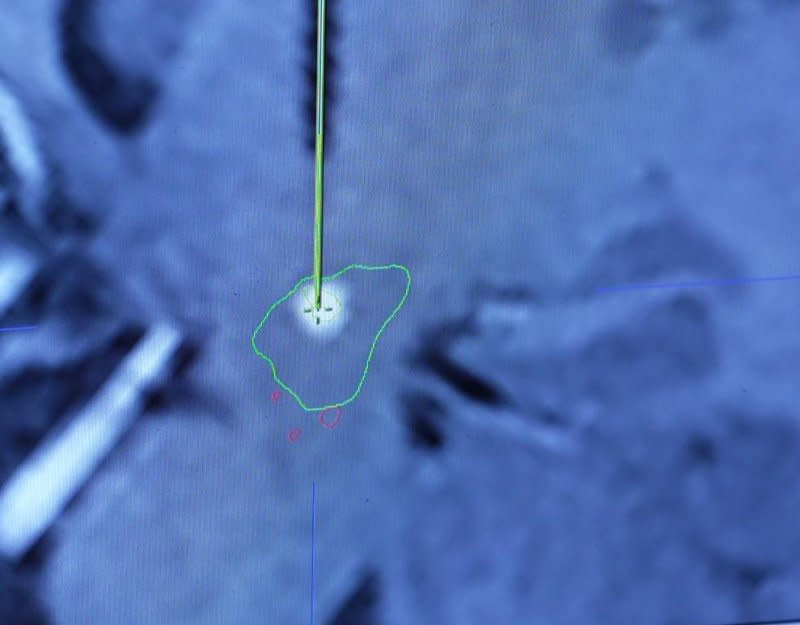

With targeted delivery of gene therapy to specific areas of the brain using real-time MRI, researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center's Gene Therapy Institute in Columbus are exploring avenues to improve the lives of patients with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, brain tumors and other neurodegenerative disorders.

"The recent refinements in gene therapy have allowed for an increase in disorders to be treated," said Dr. Russell Lonser, chair of the department of neurological surgery and director of the Gene Therapy Institute. At Ohio State, "clinical trials are going to use gene therapy for treatment of epilepsy and ALS," he said.

Previously untreatable

While risks are inherent in any surgery, "the potential benefits could be disease reversal in a disorder that's previously untreatable," Lonser said, adding that gene therapy also could lessen the severity of disease symptoms that current medications don't relieve.

One of the institute's major achievements is the development of gene therapy to treat a rare genetic disorder called aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, or AADC, deficiency, which can cause delays in a child's development.

Children with this disorder lack an enzyme that produces the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin -- chemical messengers responsible for regulating numerous functions and processes, from sleep to metabolism.

This disruption impairs coordination of movements involving the head, face and neck, hindering these children from sitting up or walking by themselves.

It's estimated that fewer than 1,000 people worldwide have this deficiency, according to the Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center at the National Institutes of Health.

Among them is 9-year-old Delilah Ramirez, who traveled 800 miles from her home in Papillion, a suburb of Omaha, Neb., to undergo life-changing gene therapy surgery at Ohio State in July 2022.

At the time, Delilah, who has lived with this condition since infancy, depended on a motorized wheelchair. She couldn't feed herself or sleep through the night. She had emotional outbursts and suffered from seizure-like episodes that could last hours.

"The surgery has done miracles for Delilah," said her mother, Arcelia. "Delilah is now able to stand from sitting on a raised surface. She can walk, finger-feed herself, sleep about 8 to 10 hours, is able to control her emotions a lot better and has become more proficient with her communication device."

Delilah's mother said she is grateful to the doctors and research foundation that made the surgery possible.

Life-changing experience

"It has been a life-changing experience for her, and we can't wait to see how much more she can accomplish," she said. "We continue to be in awe of the many developmental improvements she has made in such short time."

Dr. David Williams, chief of hematology and oncology at Boston Children's Hospital, said gene therapy has been in development since the early 1980s, but recently accelerated with the FDA's approval of various treatments in the last 1 1/2 years.

"It's very exciting to see investment in basic science that occurred for many years starting to pay off with new treatments for bad diseases," said Williams, a gene therapy pioneer, who also is a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

Boston Children's Hospital offers the latest gene therapy for childhood cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, or ALD, a deadly genetic condition that destroys the protective sheath surrounding the brain's neurons. The childhood form of this disease is the most devastating, according to the ALD Alliance.

ALD typically affects as many as 1 in 17,000 males, striking between ages 4 and 10, and healthy boys abruptly begin to regress, sometimes exhibiting minor behavioral difficulties, such as withdrawal or trouble concentrating, vision problems or coordination issues.

As the disease spreads throughout the brain, a child's health spirals downward, causing blindness, deafness, seizures, loss of muscle control and progressive dementia. This leads to a vegetative state or death usually within 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.

"If you don't treat the disease, you generally don't survive into adulthood," Williams said. "Gene therapy is an amazing treatment for some patients for some diseases. Of course, it's not widespread yet because it's so new."

Transformed lives

Gene therapy has transformed the lives of children and adults with rare genetic disorders, such as spinal muscular atrophy, hemophilia and severe combined immunodeficiency, said Dr. Hideho Okada, a physician-scientist and director of the UCSF Brain Tumor Immunotherapy Center at the University of California-San Francisco.

"The fundamental difference between gene therapy in general versus drug therapy is that gene therapy effects can stay for a long time, possibly for the rest of the patient's life, because it corrects the disease at the genetic level," said Okada, who conducted one of the first immune gene therapy trials in 2000 for malignant glioma, a type of brain tumor.

Physicians and other health care team members, such as pharmacists and nurses, need special training to perform gene therapy, said Dr. Terence Flotte, executive deputy chancellor and provost of UMass Chan Medical School and dean of the T.H. Chan School of Medicine in Worcester, Mass.

It's difficult to tell how broadly clinicians will be able to apply gene therapy in the future. So far, this technology's impact has been the greatest on children with rare genetic disorders, said Flotte, who is vice president of the American Society for Gene and Cell Therapy.

Since the FDA approved the first gene therapy in 2017, "the field is no longer in its infancy," he said. "But it's certainly not fully mature yet."