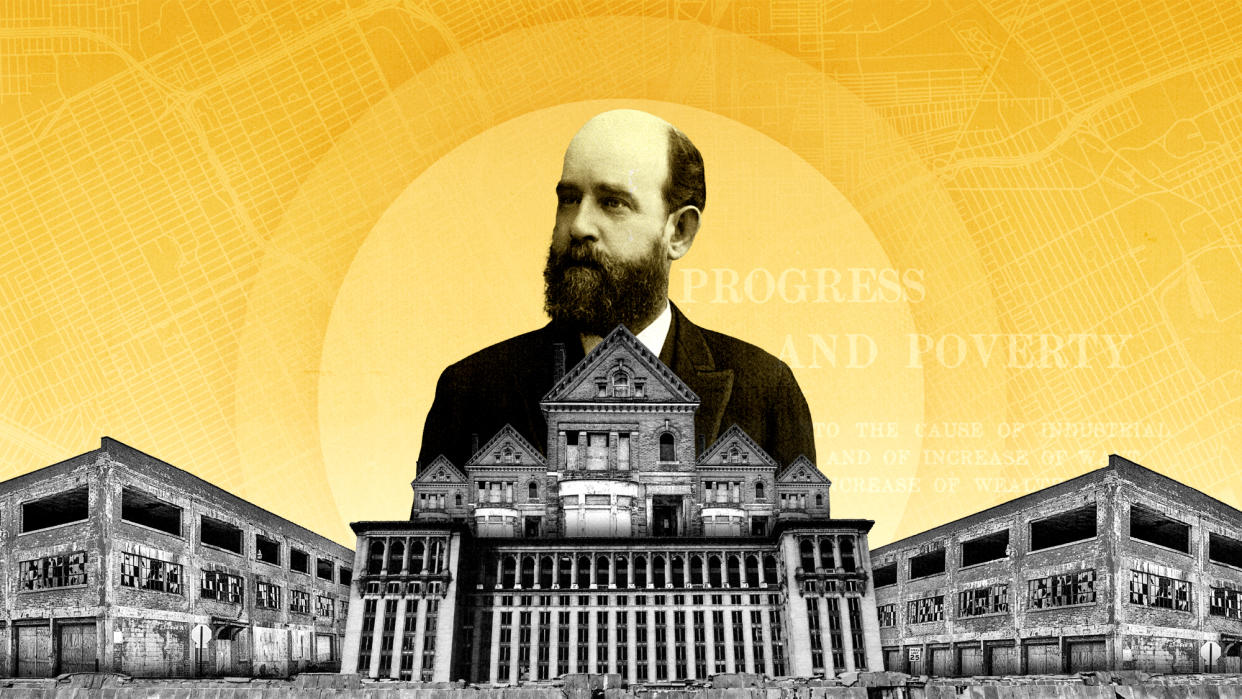

Is a Georgist tax on land the solution to Detroit's housing crisis?

Detroit is just a decade removed from becoming the largest city in American history to file for bankruptcy, and the Michigan metropolis continues to struggle economically even 10 years later. While Detroit's downtown area has seen a massive revitalization effort, many properties on the outskirts have fallen into dilapidation and disrepair. And though an estimated 20,000 abandoned homes have reportedly been demolished in the last decade, thousands more remain.

Leading the push for a change is Mayor Mike Duggan (D), who has led Detroit since 2014. Duggan has consistently decried Detroit's current property tax system as the tool that is driving the city's housing crisis. In response, he has proposed a little-known solution: decrease Detroiters' property taxes and increase taxes on derelict parcels of land instead, a concept known as a "land-value tax."

The land-value tax is one of the foundations of Georgism. This is an economic principle stating that land should be the responsibility of the entire community and not individual citizens — basically, valuing the land itself and not the structure on top of it. As such, Duggan's proposal would "cut homeowners' taxes by an average of 17% and pay for it by increasing taxes on abandoned buildings, parking lots, scrapyards and other similar properties." However, this type of tax has attracted significant controversy, with proponents heralding it as a necessary idea and critics calling it improbable.

What the commentators said

Duggan's type of land-tax policy proposal is not seen in any comparable American city, partially because proponents of Georgism "are regarded as the tinfoil-hat-wearers of economics," Conor Dougherty reported for The New York Times. This feeling comes from the fact that many Georgists "believe that if America were to throw out all taxes, then replace them with a single land-value tax, it would end poverty and recessions for good," he added.

While this theory of a perfect economy is "plainly unrealistic," Duggan's proposal does shed some insight "about urban economies and how to improve them," Dougherty said. "It’s like there’s this tool in our toolbox that could help solve a lot of our problems, and we refuse to pick it up," Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at the real estate brokerage Redfin, told the Times. "If more people understood how useful this was, they would advocate it."

The most immediate change from this plan, though, "comes from reducing taxes on most residents," wrote the U.S. correspondents board of The Economist. Since lower property taxes will allow homeowners to make more improvements to their houses, Duggan's plan "ought to encourage people to invest in properties — and help some avoid falling behind on their taxes," the outlet added.

However, the plan also has a number of opponents, such as the Coalition for Property Tax Justice. The coalition has argued that the land-value tax "does nothing about the city of Detroit’s systemic and illegally inflated property tax assessments," per Michigan Advance. "The city of Detroit has overtaxed homeowners by $600 million and it’s time to get to the root of the problem" instead of worrying about a land-value tax, coalition member Bernadette Atuahene told the outlet.

What next?

While Duggan is keen on the idea of his land-tax plan, it first has to be approved by the Michigan legislature, then go through the Detroit City Council before a final referendum from voters.

However, Duggan's plan is currently stalled in the state House, which recently broke for the remainder of this year. If it had been passed by the legislature, then the City Council would've had to "decide by November 2023 whether to place the issue on the ballot," per Duggan's agenda. The referendum would've then gone to the voters in the February 2024 presidential primary.

However, given the legislature's adjournment, this timeline will clearly not come to fruition. Duggan has been pushing a change to the city's tax code for a long time, though, so it is likely that this is an issue that will remain at the forefront of Detroit politics for the long haul.

And for what it's worth, Duggan doesn't consider himself a Georgist, and told the Times he had never even heard of the inspiration behind the idea, Henry George. "This isn’t any deep philosophical movement," Duggan said. "I’m trying to cut taxes."