Giorgia Meloni: One year at the helm of Italy's most right-wing government since 1946

On 22 October 2022, Italy's most right-wing and Eurosceptic government since 1946 took office in Rome. The victory of Giorgia Meloni's party in the Italian elections raised concerns among European democracies.

One year on, what assessment can be made of the Italian Prime Minister's policies? Has she succeeded in erasing her neo-fascist image, particularly abroad?

Between neo-fascism and populism

"I'm what the British would call an 'outsider', so to speak, the 'underdog', the one who, to succeed, has to upset all the predictions. That's what I intend to do again, upset the predictions." That's how Giorgia Meloni described herself to the Italian Parliament when she delivered her inaugural speech on 25 October 2022.

"From a factual point of view, the idea that Giorgia Meloni is an 'underdog' and that she is humble is false", said Gianfranco Pellegrino, a lecturer in political philosophy at the Luiss University of Rome.

"Giorgia Meloni has been in politics for over twenty years. She is not a newcomer. From a financial point of view, Giorgia Meloni is certainly not a proletarian, because her standard of living is very high", he told Euronews. "So even the word 'underdog' and the image it conjures up is a rhetorical attempt based on real propaganda lies. Presenting yourself as particularly close to the people is a rhetorical technique, typically populist".

Experts say that on migration policy, international relations and domestic policy, Giorgia Meloni has failed to show her closeness to the people or to dissociate herself from the neo-fascist image that follows her.

"There has certainly been an attempt to distance herself from the neo-fascist label. However, this attempt seems to me to have been only partially successful," Gianfranco Pellegrino added.

And yet, according to the polls, if Italians were called to vote today, Pellegrino believes that "the picture would be no different... I don't think there would be a big victory for the left."

According to an Italian poll carried out on 16 October, her Brothers of Italy party has maintained its support among Italians.

Review of migration policy

"On certain issues, [Meloni] tends to wave the flag of identity. Immigration is one such example. After all, it doesn't cost much. Preaching hostility towards immigrants is not as complicated as revaluing pensions or increasing incomes," explained Maurizio Ambrosini, a lecturer in the sociology of migration at the University of Milan.

"We want to make security a distinctive feature of this government", declared the Prime Minister on the day of her election victory, "and put an end to illegal departures by finally breaking up human trafficking in the Mediterranean."

Following a key point in the political programme of Matteo Salvini, leader of the right-wing League party, Meloni's government had expressed its intention to create a "naval blockade" to halt the arrival of migrants on the Italian coast.

This blockade would have taken up the initial proposal of the European Union's naval mission, Operation Sophia, which, in its planned-but-never-implemented third phase, specifically envisaged blocking the departure of boats from North Africa.

"Unless we decide to wage war on our North African neighbours, this would appear to be an impractical measure or one with costs that would have to be seriously considered", explained Maurizio Ambrosini.

Meloni herself recently told the press that, as far as migration policy is concerned, "the results are not yet as hoped."

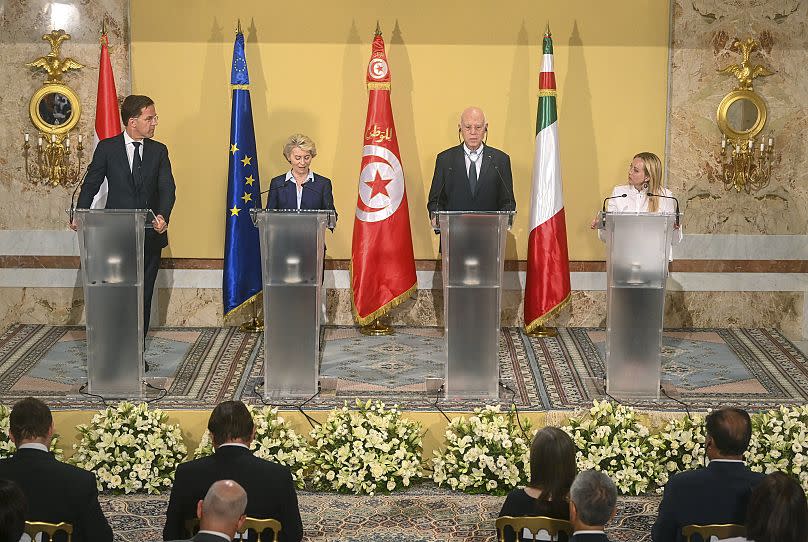

Two months ago, after working actively on this issue, Meloni announced the signing of a pact with Tunisia. Alongside her were Tunisian President Saïed, European Commission President Von der Leyen and Dutch Prime Minister Rutte.

Brussels pledged to pay Tunisia €900 million, including €105 million for border controls, in exchange for the country's commitment to curb the arrival of migrants.

"However, it seems that these agreements are struggling to become operational", revealed Maurizio Ambrosini.

"The problem is that a large proportion of those leaving are Tunisian citizens, and in general the governments of neighbouring or coastal countries are more willing to collaborate when it comes to curbing the mobility of another country, but not of their own citizens", he added.

According to data updated on 19 October 2023 by the Italian Ministry of the Interior, 140,898 migrants landed on Italian shores in 2023, almost double the number in 2022.

At the EU Council of Home Affairs Ministers held in Luxembourg on 8 June, the 27 EU countries reached an agreement on immigration that would replace the Dublin III regulation, introducing quotas for the relocation of migrants to the various European states.

"But even this strategy is not working, because it is precisely Italy's eastern partners (Hungary and Poland) and those who are politically allied to the forces in power in Italy who are not cooperating and are obstructing these relocation agreements in every possible way", explained Maurizio Ambrosini.

According to Ambrosini, Giorgia Meloni's migration policy is strikingly ambiguous.

"The generous welcome given to Ukrainians is an extraordinary case of double standards and double talk on immigration and asylum, according to which refugees from certain wars in Afghanistan, Syria and other countries of the South and Africa are not welcome, do not please us, and do not arouse solidarity movements. We like the Ukrainians," he told Euronews.

"It seems to me that this year has been marked by setbacks in terms of respect for human rights and solidarity. I'm also thinking of the persecution of NGOs. I think that the Cutro decree reduces the possibilities of obtaining asylum in Italy."

"On the other hand, I am interested in the openness towards workers... More possibilities of entry for work reasons seems to be a good solution, especially as companies are asking for it and they can perhaps represent, at least in part, an alternative to risky journeys by sea. However, a policy for integrating these workers needs to be planned," Maurizio Ambrosini explained.

A difficult year for civil rights

"The three most important measures in terms of civil rights were the bill to make PMA a universal offence; the measure that encouraged prefects not to automatically recognise children born through PMA abroad and the measures relating to the birth rate that are included in the Finance Act. The latter offer incentives to facilitate access to crèches as well as economic benefits for working mothers with more than two children", explains Gianfranco Pellegrino, lecturer in political philosophy at the LUISS in Rome.

In March, the Meloni government launched an offensive in favour of the traditional family. A circular was issued asking municipalities to stop registering non-biological parents in the birth certificates of children with two fathers or two mothers. Then there was opposition to a proposed European regulation on the subject.

In Italy, surrogate motherhood is banned. As a result, many same-sex couples go abroad to have a child. Once back in Italy, the question arises of how to have their children recognised on the national registers, and here again, problems arise. There is no law on the recognition of parentage for same-sex families, which means that only the biological parent is recognised.

For some years now, some municipal authorities have allowed the names of both parents to be entered when the birth certificate is signed at the registry office, which functions as a real recognition. But the Prime Minister has blocked this move.

Meloni has argued that women with more than two children make a bigger contribution to society.

"There is the idea that the natural family resulting from a heterosexual union is the basic cell of society", claimed Gianfranco Pellegrino, "and that it is right to discriminate against unconventional families, i.e. families made up of same-sex couples, single-parent families or people who choose not to have children. These individuals would thus be discriminated against, being considered less valuable by the State."

Foreign policy: Between Europeanism and sovereignty

Over the last twelve months, Meloni has had to abandon her initial anti-Europeanism.

"Her fundamental objective was to consolidate a reliable image. Different from the one that had been portrayed by the international media", Cecilia Sottilotta, a political science lecturer at the University for Foreigners in Perugia (Unistrapg), told Euronews.

"The situation could be described as follows: Italy needs Europe as much as Europe needs Italy. As a result, Meloni has had to find a way of working with the European institutions and vice versa, the European institutions have had to make an effort to work with her," she added.

Giorgia Meloni has repeatedly stressed the need to support Ukraine during the war, even though parts of her government have expressed admiration for Putin, such as Matteo Salvini and the late Silvio Berlusconi.

Meloni's position has also evolved over time. After Moscow invaded Crimea in 2014, she regularly opposed sanctions against Russia, arguing the need to protect Italian exports.

In a TV interview in 2022, before Russia's full invasion of Ukraine, she stressed the importance of maintaining good relations with Putin.

"Yet of the three right-wing parties, Brothers of Italy is certainly the least pro-Putin," said Cecilia Sottilotta.

"Meloni has had to face some difficult moments, because we remember when Berlusconi spoke very explicitly in favour of Putin, defending him and attacking Zelenskyy. We remember the Salvini scene, with the famous T-shirt bearing Putin's face in Red Square. All in all, this was clearly a source of embarrassment. However, given that Brothers of Italy was the least exposed party in relation to Russia, it was relatively easier for her to distance herself from it."

On 14 September 2023, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, a right-wing nationalist, made no secret of his satisfaction at reconnecting with his friend Giorgia Meloni, a regular visitor when she was in opposition.

In the course of this year, the Prime Minister has also met Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki three times.

"At the European level, Meloni is still allied with governments such as Orbán's in Hungary and Poland," Cecilia Sottilotta explained. "Does she aspire to become an attractive force for the right in general? Possibly. To understand that, we'll have to watch the next European elections carefully."