Government 'Sunshine List' will drive wages up, productivity down says university prof

A political scientist says history shows that releasing the names and salaries of top government employees is an ineffective tool for reducing the size and cost of the civil service. If anything it could prove to be counter-productive.

Ontario premier Mike Harris tried that strategy when he made the Sunshine List part of his "common sense revolution" 20 years ago. And did it work?

"No." That's the short answer from Zachary Spicer, assistant professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario. "Here, the (number of names on) the Sunshine List has increased every single year since."

Spicer said the Ontario Conservatives introduced their Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act because they believed shining a light on what they believed were excessively high government salaries would outrage the public, who would in turn call for restraint.

"Over time the government would have some rationale for reducing the size of the public service," he told CBC Radio's St. John's Morning Show.

But in this case political theory never did line up with fiscal reality. In 2014 the number of people who made Ontario's Sunshine List jumped almost 14 per cent from the year before. There were 111,440 names in all.

Coming soon in NL

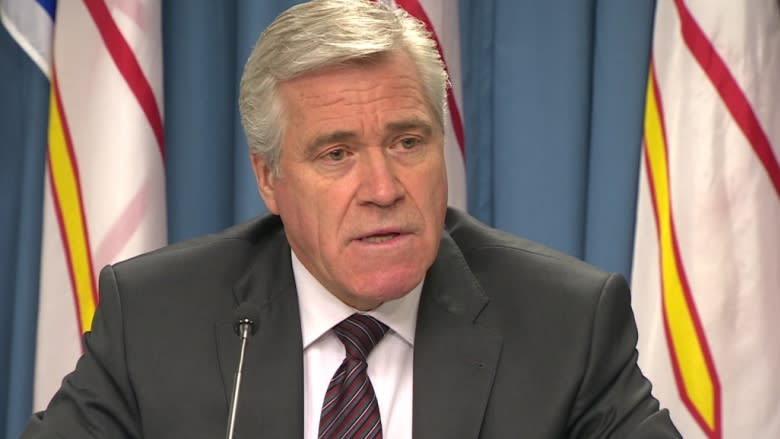

Dwight Ball announced June 7 that his Liberal government would introduce it's own Sunshine List legislation this fall. That would make Newfoundland and Labrador the sixth province to publish the names and salaries of it's most expensive employees. Ontario, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Alberta and British Columbia are the others.

"The Sunshine List gives us a good idea where money is spent but gives us no indication of value," he said. "We may not know how many years that person has actually been there. We don't know what they've done in the past ... We have no idea about the value that person provides to the government."

Spicer says the biggest problem for government is that having a Sunshine List may be counter productive by driving salaries up and productivity down. He says a 2012 study in the American Economic Review backs that up.

"It gives every government worker a very good benchmark to see what their counterparts are making," Spicer said.

Which means they have a valuable tool when it comes time to renegotiate their own salary.

"I do much more work that that person. I'm better at my job than that person. Why are they making more than me? Or people simply get upset. They get angry and they get resentful. Which ultimately makes them worse at their job. And can perhaps increase workplace hostility. "