Governor kills plan to allow seawalls, pay property owners accused of violating beach law

Gov. Henry McMaster vetoed Wednesday the Legislature’s plan for the state to compensate affluent oceanfront landowners accused of violating South Carolina’s beach management law, a 36-year-old statute meant to protect the seashore for the public.

At a news conference inside the State House, the governor said the effort to shield property owners from some parts of the state’s coastal law was rushed and could expose the state to significant financial liability.

Two budget provisos, passed late in the Legislative session without public hearings, would have made it easier for property owners to stop state decisions that are intended to protect the public beach.

They could have affected hundreds of millions of dollars in seaside property, potentially allowing for construction of seawalls now banned by state law, while having taxpayers compensate property owners who win legal challenges against the state. The provisos could have led to a flurry of legal cases, critics have said.

“A piecemeal attempt to address beach erosion and management through provisos, which are only in effect for one year, is not good policy,’’ the governor said in his veto message.

McMaster’s decision Wednesday isn’t his first regarding seawall construction. In 2019, he vetoed legislation that would have allowed reconstruction of a battered seawall at Debordieu, an exclusive beach community in Georgetown County where a row of homes jut far onto the beach. At the time, McMaster said the legislation was rushed and needed more scrutiny by the Legislature.

South Carolina’s struggle with coastal management is occurring as the state faces increasing threats from rising sea levels and more intense storms, both of which are threatening to wash away oceanfront homes on many parts of the coast, including beaches near Charleston and south of Myrtle Beach.

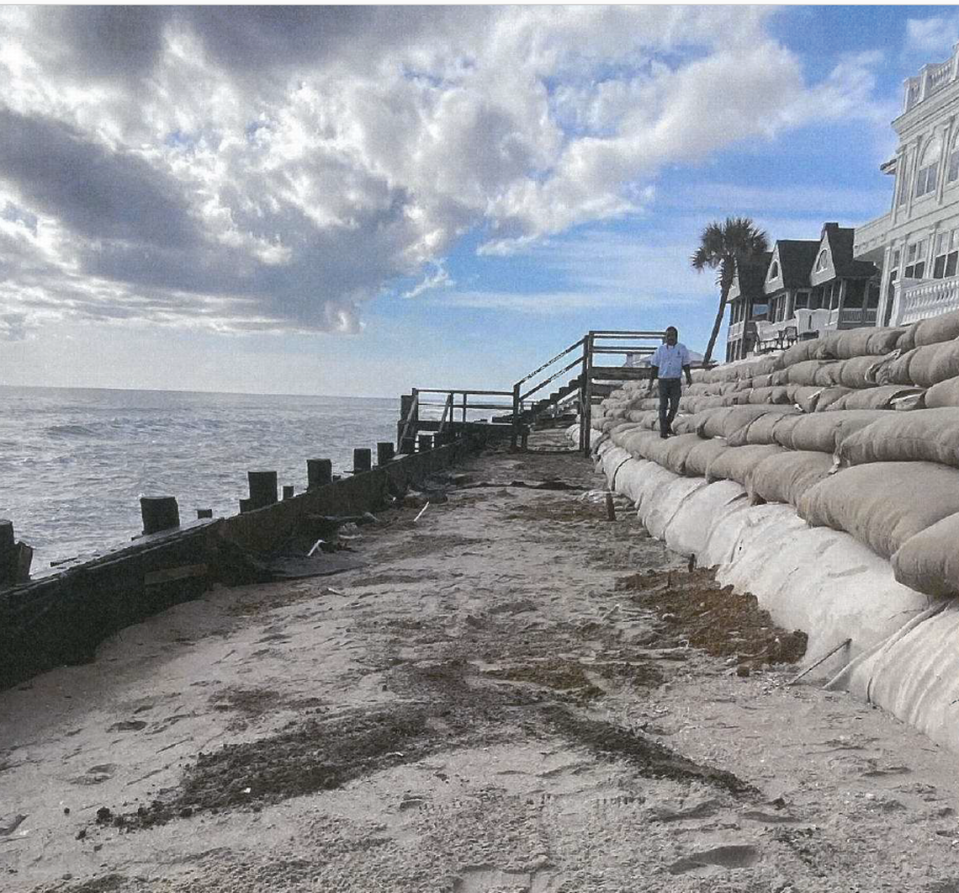

As a result, property owners have been scrambling to find ways to protect their homes with seawalls and huge walls of sandbags. But new seawalls are illegal under the state’s 1988 beach management law and state regulators have cited scores of property owners for erecting seawalls, bulkheads and other measures to fend off the waves.

While seawalls and hard sand bag walls offer some protection for private property, they can block public access on the beach and also worsen beach erosion as waves pound the walls. When beaches erode, it can hurt tourism that provides a hefty boost to South Carolina’s economy.

Leslie Lenhardt, a lawyer with the non-profit S.C. Environmental Law Project, said McMaster made the right decision.

“This really would have been a blow, a blow to our tourism industry,’’ she said, noting that an explosion of seawalls means South Carolina “would end up with just no beach.’’

Emily Cedzo, who has tracked the proviso effort for the Coastal Conservation League, expressed relief and gratitude at McMaster’s decision.

“We are very grateful for Governor McMaster’s vetoes on the harmful beach provisos,’’ she said in an email. “He has been a constant leader in protecting our state’s beaches for the benefit of all who rely upon them. These vetoes make clear that our state agencies should be entrusted to implement longstanding, thoughtful policy and that new seawalls have no place on South Carolina’s beaches.’’

The provisos , pushed by Sen. Stephen Goldfinch, came out of the Senate and were approved by a budget negotiating committee last month. The committee did not say why it was approving the beach provisos, but voted 5-1 to include them in the state budget. Only Rep. Leon Stavrinakis, D-Charleston, voted against it, saying the plan needed more scrutiny.

One of the provisos allows property owners to more easily challenge state determinations of where the beach starts. Property owners would be able to immediately appeal such determinations by state regulators to the Administrative Law Court, a provision not now spelled out in state law.

Then, if property owners successfully challenged where jurisdiction over the beach begins, they could build or keep seawalls, while also recouping their attorneys fees and other costs of making the challenge.

The other proviso required the state coastal agency to reassess enforcement cases against oceanfront property owners made in the past six years.

If it is determined that property owners involved in enforcement cases would later not be in violation -- if the state’s jurisdictional limits on development change -- taxpayers must pay the legal fees homeowners incurred fighting the state. It also could allow the property owners to keep seawalls or sand bags they had already installed.

That could cost taxpayers $2 million if the state lost the 100 or so cases it has made over seawall issues since 2018. But it could be more.

Some lawyers say the provisos could have encouraged more legal cases challenging limits on coastal development because property owners would know they could potentially get their money back.

Both provisos were supported by Goldfinch, a Georgetown County Republican, who has backed oceanfront landowners who are battling the S.C. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management over the use of seawalls and sandbags.

Goldfinch has worked for some landowners as a private attorney, and while as a senator, also pushed changes in state rules that could help seaside property owners.

Erosion hot spots where property owners could have benefited from the provisos include the Isle of Palms, the Debordieu resort near Georgetown, Harbor Island outside Beaufort, Garden City south of Myrtle Beach and the southern tip of Litchfield Beach, a thin strip of sand near Pawleys Island where houses were developed in the 1990s after Hurricane Hugo blasted the property.

South Carolina’s battles over seaside development are not new, dating almost to the inception of a 1988 law that was intended to address beach erosion by slowly moving new development away from the immediate seashore. The law banned new seawalls.

But with climate change raising sea levels and helping to intensify coastal storms, those battles are intensifying and legislators are listening to affluent landowners about helping them gain relief.