What happened to the bells at Trinity Church?

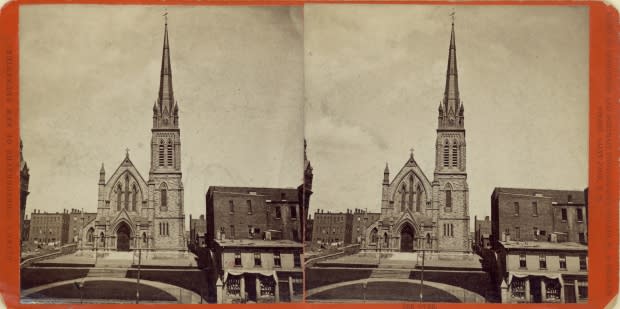

The spire of Trinity Church has put an exclamation point on the Saint John skyline for 140 years.

Sailing ships used its giant, salmon-shaped weather-vane to navigate into port. Its tolling bells marked the time for generations of Saint Johners. The Trinity Royal heritage area is named after it.

"It's one of the most iconic features of uptown Saint John," said church warden Derek Oland.

But five years ago, a single stone that tumbled from the steeple signalled a landslide of structural issues for the 1879 building.

"We saw one stone come down," said Oland.

Then an inspection revealed "there were a lot more that were going to go."

Hard lesson

The problem, construction crews discovered, was a 1960s repair job undertaken with Portland cement — a construction material widely used because of its cheapness and ultra-strong bond.

It was "a newer type of mortar that was supposed to be the answer to everyone's prayers," Oland said. "That's what they used to bind the limestone and sandstone to the steeple."

But that turned out to be a fatal mistake.

"They figured stronger was better — and it wasn't, in this case," said Ryan Gagnon with Coastal Restoration & Masonry Ltd., the Nova Scotia company hired to do the repairs.

"Portland is very strong — stronger than the stone itself."

The mortar dried so hard that it cracked in Saint John's freeze-thaw cycle, allowing water to get in.

"Something has to give somewhere," Gagnon said. "Unfortunately, it's been the stone."

The foundation remains strong — but in the steeple there are "many, many cracks," Oland said.

"We decided that to preserve the steeple, and also to prevent it becoming a danger to people walking around it, to fix it."

Horse and buggy, hard labour

The stones of Trinity Church are hand-shaped limestone and sandstone from the 1800s, according to Bill Quinn of CRM, who has done restoration work on buildings across Atlantic Canada, including the Carleton Martello in west Saint John, built in 1815.

"The stonework is beautiful," he said.

"The stones have never been changed, so they were in really great shape — other than the mortar."

It's a far cry from the buildings of today, Quinn said.

"Stonework today, a lot of it is cultured stone," he said. "It's just pieces, and you more or less glue them in. But this — everything is solid and built to each other and locked in."

The stones would have been carted up the hill "by horse and buggy, ropes, or just straight labour," he said. "Nowadays we have chain falls and electric hoists.

"It's a lot easier."

Biggest renovation in decades

But the repairs are no mean feat.

The stonework must be repointed — the mortar chipped and jackhammered out from between tens of thousands of stones, then filled in with a less crack-prone material.

"The mortar we'll use will be more of the old-fashioned mortar, which is much more forgiving of our climate here," Oland said.

Crews started work in March, encased the High Gothic steeple in plastic-wrapped scaffolding.

It's the most substantial renovation the church has seen in many decades.

"This contract here will be almost $400,000, and then there are other costs as well," Oland said.

The first phase of construction will be on the south and east face of the building.

"Then we'll do the north and west face next year, and there's other work we're going to be doing on the interior up here in the third phase," Oland said.

Trinity Church has raised approximately half of the projected $1 million cost of the renovations.

"We have decided that we are not going to borrow money for this project," Oland said.

"If we can't raise the money, we are just going to have to postpone the phases until we have sufficient funds."

Cathedral, Gothic Arches

Trinity Church isn't the only historic Saint John church that needs serious TLC.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception on Waterloo Street, opened in 1853, has raised more than $3.5 million over the past decade to repair its roof and still requires significant repairs.

The Gothic Arches — once one of the grandest Methodist churches in the city — has been vacant and intermittently threatened with demolition since the 1990s.

The first phase of renovation on Trinity is expected to be complete by this fall.

That's when the church bells — decommissioned during the work — will be heard again in uptown Saint John.

"It was the church that the Loyalists started when they arrived in Saint John in the 1770s," Oland said.

"Cities need to respect their past. Churches are an important part of that."