And her name was NOT Marco Polo

The cry of seagulls. Wind in the sails. The creak of masts and rigging.

Images such as these have captivated Harley Stanton for more than two decades.

Since 1999, Stanton has been engrossed in a genealogical voyage of discovery, retracing the migration of his ancestors from England to Australia in the mid-1800s.

The project led him to discover and write about the illustrious history of a 168-foot sailing ship built in Saint John called the Conway.

Survived a lot in 26 Atlantic crossings

The Conway travelled more than 500,000 miles, Stanton discovered.

It crossed the Atlantic 26 times, through cyclone, mutiny, legal wrangling, attempted scuttling and cholera outbreak.

Among the many who survived their voyage on the Conway were Stanton's great-great-grandfather, Thomas Stanton, a lower-middle-class farmer from Cambridge, his wife and their four children.

They migrated to what was then known as Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, seeking to improve their lot in life.

Many of the fastest ships of the golden age of sail were built in Saint John.

'A wonderful ship'

But to Stanton, the Conway was a ship like none other.

"She was not really probably the truest clipper ship, but she was a wonderful ship," said Stanton.

The Conway was constructed in 1854 by partners John Owens and John Duncan, who co-owned one of the largest shipbuilding companies in the city.

At the time, Saint John was the third-biggest shipbuilding centre in the world.

It also also produced the celebrated and speedier Marco Polo, which the Conway followed in joining James Baines & Co.'s Australian line.

The Liverpool-based line's ships collectively brought 500,000 people to Australia in the 1840s and '50s.

Aboard the Conway on the very same voyage as Stanton's ancestors, to name just one noteworthy family, were the Blundstones, now famous for bootmaking.

Australia was still a penal colony then, but by 1853, transportation of new convicts had all but stopped and a gold rush had begun.

Land was selling for a shilling an acre, and there was an urgent, advertised need for servants, labourers, shepherds, sawyers, fishermen and tradespeople of all kinds.

"In those days, it was really important to try and make the ships arrive at the most speedy time that they could," said Stanton.

The fastest trip from England to Australia was completed in 63 days, he said.

Slower than record-breaker

The Conway didn't come close to that. It took an average of 90 to 95 days.

But it had a number of "unique features" that set it apart, including eight feet between decks and ventilators that provided air to the lower levels.

Stanton began his research hoping to find an illustration of the Conway.

He looked all over the world and couldn't find a single one.

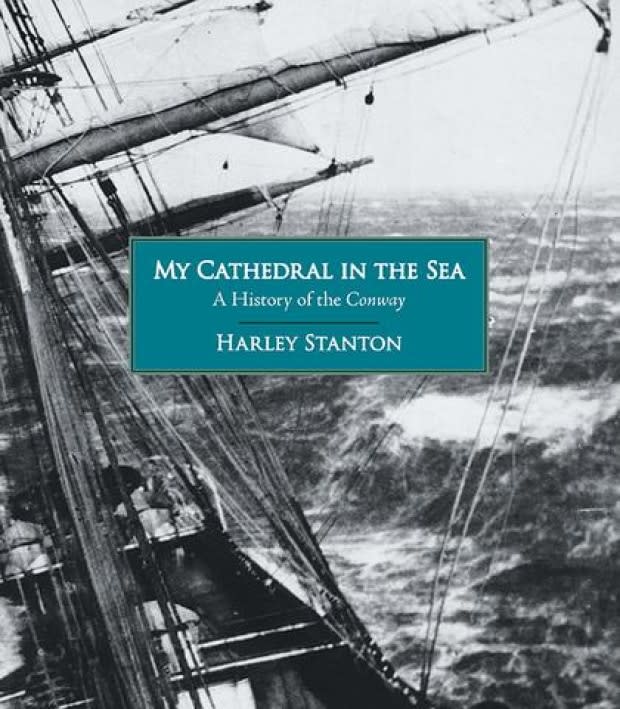

But he did turn up a wealth of other information that he used to write a new book called My Cathedral In the Sea: A History of the Conway.

An entire chapter of the book is devoted to Saint John, which Stanton visited in 2005.

He planned to stay a couple of days and ended up staying a week.

"It was a real catharsis in my life," he said of the trip.

"I think it was one of those serendipitous moments ... you just can never forget."

"I wandered down onto the foreshore there and saw the Reversing Falls, and I met so many people of phenomenal interest to me while I was in Saint John."

Saint Johners eager to help

Among them were local historian Harold Wright and Norton Wyse, a former volunteer at the New Brunswick Museum.

Meeting others who shared his passion for shipbuilding history made him feel "much at home" in the Port City.

People seemed to "come out of the woodwork" to provide him with material — from pictures of logs being hauled over the ice, to a lithograph map of 1864 Saint John hand-coloured by Linda Cook, and poems by Bliss Carman.

"To discover what it actually took to build the ship and to go to the museum and see the shipbuilding materials and the way the ship was actually built gave me a whole new dimension of understanding of what it was about."

Stanton said he hopes his book gives people a better understanding of the oversea voyages aboard clipper ships taken by so many migrants in the 19th century.

The Conway returned to its home port in 1866 on its way to Quebec.

It had been contracted to carry military supplies.

It set out on its final voyage in 1875, during which it was abandoned near the Sargasso Sea.