He's waited years for justice in his brother's workplace death. Now he may never get it

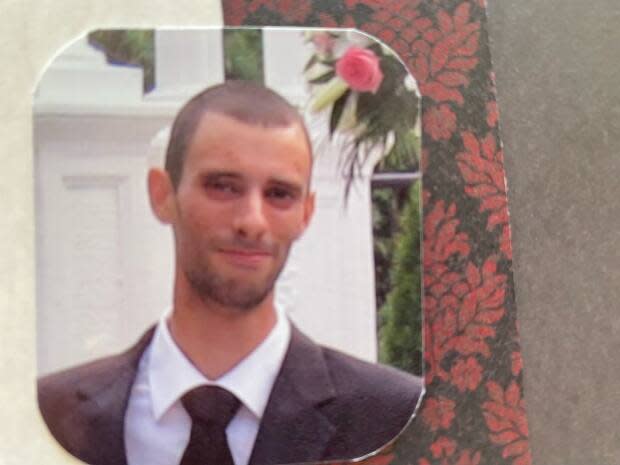

It's been almost three years since David Panepinto's brother Chris died on the job at a construction site, but he says his family is no closer to understanding what happened to him that day.

Christopher Panepinto, 33, was crushed by a temporary barrier on Feb. 10, 2020, Panepinto says, while he and other workers were forming concrete for a new retirement community in Pickering, Ont., east of Toronto.

"We still don't have any answers at all of what really happened, and why," Panepinto told CBC News.

The construction company, Delgant Limited, was charged last July with multiple health and safety violations in connection with his death — something the Panepinto family saw as their chance to finally find out what happened.

But they learned recently that day won't come. In an email to the family, the Crown said it withdrew the charges on Dec. 5 after it concluded it couldn't finish the case within 18 months, the timeline established for provincial offences by the Jordan decision, a 2016 ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Crown said it couldn't meet that timeline due to an "abysmal and unacceptable" lack of judicial resources at the court handling its case.

"We lost him, and now we lost the chance for justice," Panepinto said.

Panepinto says the withdrawal of charges was a shock to a family that's waited too long for accountability. Their story, according to one expert, shows accountability through a struggling court system isn't always guaranteed.

For Panepinto, the lack of resources doesn't justify dropping the case, or give him cause to believe the company will be held accountable for any future infractions.

"To watch this case get dismissed after having our hopes raised, it's really had a very negative impact on our family," he said.

'Everybody's a worker'

Panepinto is concerned his brother's case is falling through the cracks, especially given the company's track record — according to online court records, Delgant Limited was charged and fined $300,000 in 2005 after two workers fell to their deaths.

While the most recent charges have been withdrawn, that doesn't mean the company is absolved of any wrongdoing, said Carmine Tiano, the director of occupational services at the Provincial Building and Construction Trades Council of Ontario.

"The person lost his life. There's no solace in that," said Tiano.

The treatment of the case shows society might not value accountability for a construction worker's death, TIano says, as much as it would for emergency responders, or for victims whose cases fall under the criminal system, instead of provincial court.

"We need to get better at personalizing what's happening, because everybody's a worker," he said.

The Ministry of Labour conducted two "proactive" visits to the company since Christopher's death and found it in compliance with healthy and safety laws, along with orders issued after the fatality.

Delgant Limited did not respond to CBC Toronto after multiple requests for comment.

Who should be held accountable?

According to George Bazios, the manager of court services at the Region of Durham, the only provincial offences court in the region is still operating at less than 50 per cent capacity compared to pre-pandemic times due to current judicial resourcing.

Neither the local court, the Ministry of the Attorney General or the Ontario Court of Justice would clearly answer who's responsible for the lack of resources that led to the delay.

The Ministry of the Attorney General didn't comment on the state of judicial resourcing in the province when asked to. Instead, the ministry said the Ontario Court of Justice has "exclusive authority" over the scheduling of court proceedings and what matters it decides justices of the peace will hear.

"It would be inappropriate for the Ministry of the Attorney General to comment on or interfere with the scheduling of matters," reads the ministry's statement.

Meanwhile, the court says it's the ministry that administers the courts and can speak to the state of judicial resources.

No matter who's fault, if courts are left to make due, that forces them to triage cases in ways that won't always seem fair to Ontarians, said Melanie Webb, a criminal lawyer and council member of the Ontario Bar Association.

"It may very well be a just decision. It may just not be the decision that everyone would want to see," said Webb.

Municipalities across Ontario were struggling to administer timely court services long before the COVID-19 pandemic, Webb says, with each jurisdiction facing unique problems such as underfunding.

Webb says the 2016 Jordan decision was supposed to be a catalyst for change that would encourage all stakeholders in the court system to proactively address issues well before cases ever reach the 18-month deadline.

"What that really tells us is that everybody needs to do better. This should motivate us all to do better."