Historians Unmask Fourth Soviet Spy Who Worked on the Atomic Bomb

Historians have unmasked a fourth Soviet spy who worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory during nuclear bomb development in the 1940s.

Los Alamos is still one of the foremost nuclear research facilities in the world.

The fourth spy was much more involved in high-level explosives research than historians could extrapolate before.

The New York Times reports that historians have unearthed a new, fourth Soviet spy who worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory during development of nuclear bombs in the late 1940s. During that time, the Soviets developed their own nuclear bomb prototype by 1949, indicating someone working from the inside of U.S. nuclear research. Codenamed “Godsend,” this spy worked closely with the development of explosive triggers for nuclear bombs.

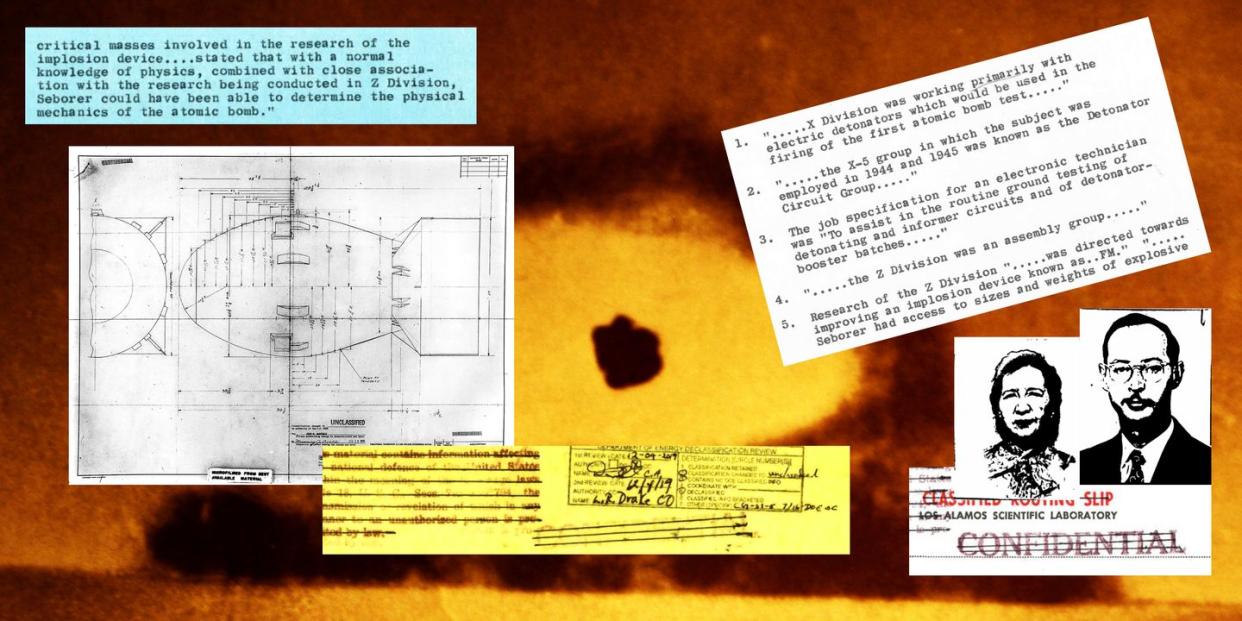

The spy was named Oscar Seborer, and although he was originally uncovered by 1956 at the latest, those papers were only declassified late last year. In the meantime, historians had used other evidence to put together a case that there was a fourth spy, codenamed Godsend, who was working at Los Alamos. They published their findings in a CIA journal called Studies in Intelligence.

When a reporter sent the academic paper to Los Alamos and asked if the laboratory had any supplementary information to share about Seborer, suddenly there were 10 pages of “newly declassified documents from 1956.” Historians had been circumspect, saying in their paper that from their evidence, “we only know that Soberer [sic] provided something.” The truth, from the declassified CIA papers, turns out to be much deeper.

Seborer and his family moved to the U.S.S.R. in 1951, and the earliest concrete record of his employment is in 1945. Six years may not sound like much, but in nuclear research, that’s a lifetime. The New York Times explains that all three previously unmasked spies were known to share information about a specific technology called an implosion device.

The first atomic bombs, including the one the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, used a cruder, less efficient explosive technology called a “gun device,” where uranium is “shot” into more uranium to cause a reaction. By contrast, the implosion device harnessed a sophisticated chain of small explosives that pushed into a core of plutonium and triggered a nuclear reaction. It required far less of the astronomically costly fuels.

“The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were roughly equal in destructiveness—but fuel for the Nagasaki bomb weighed just 14 pounds—one-tenth the weight of the fuel for the Hiroshima bomb,” the Times explains. “The secret of implosion thus represented the future of atomic weaponry.”

Plutonium makes a faster, more efficient nuclear reaction, but it simply couldn’t be used in the “gun” type of detonator. Uranium was too hard to produce and finicky to use, which had created a bottleneck in research and development of new weapons technology. To say that Seborer was involved in detonators is like saying Robert Oppenheimer was a physicist: an understatement to the point of near falsehood.

Seborer was in the front row to the development of the single piece of technology that made nuclear bombs feasible. By the time the U.S. dropped the second nuclear bomb on Nagasaki later in 1945, that bomb contained a tried and tested implosion device. The Soviets tested an implosion device of their own just four years later. Diagrams found in their declassified archives show drawings and schematics of implosion circuitry, with labels in both English and Russian, that experts believe came from spying at Los Alamos.

When Seborer and his family moved to Moscow in 1951, they adopted the name “Smith.” Oscar lived until 2015, which means that although he dedicated his life to communism, he long outlived the Soviet Union. In their paper, the historians say they believe his brother Stuart “Smith” is still alive and well in Moscow—or, at least he was in 2018.

You Might Also Like