A House You Can Buy, But Never Own

ATLANTA—It was not until a few years after he moved in that Zachary Anderson realized that he was not, in fact, the owner of the house he thought he’d purchased. Anderson had already spent tens of thousands of dollars repairing a hole in the roof, replacing a cracked sidewalk, and fixing the ceilings of the small two-bedroom home where he lives in southwest Atlanta. He was trying to get a reduction in his property taxes when his brother, who was helping him with his taxes, looked up the property in public records and found that the owner of the home was actually listed as Harbour Portfolio VII LP.

“It’s like a trick,” Anderson, a 57-year-old, told me, sitting in front of a wood-burning fireplace he’d installed in the living room of the house to lower his heating bills. “They get free work out of a lot of people.” Anderson had entered into a contract for deed, a type of transaction that was rampant in the 1950s and 1960s before African Americans had access to avenues of conventional lending. In a contract for deed, the buyer purchases an agreement for the deed rather than buying the deed itself. The tenant has to fulfill the conditions of the agreement in order to get the deed, conditions that usually include making a series of timely payments over decades, paying for home repairs and general maintenance of the home, and paying taxes and insurance on the property. If he misses one payment, thus violating the agreement, he can be evicted, losing all the equity he put into the home.

Recommended: Michael Cohen Has a Big Problem

Though half a century ago, contract-for-deed arrangements were often made between an individual real-estate speculator and a tenant, today they are more commonly made between a tenant and a big private investment company, like Harbour Portfolio Advisors, which is based in Texas and has entered into thousands of contract-for-deed arrangements across the country.

My colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates detailed contract-for-deed arrangements—also called rent-to-own deals—in his 2014 cover story “The Case for Reparations,” which looked at the prevalence of such arrangements in 1950s Chicago. What is surprising today is that, according to some housing advocates, these arrangements are in some ways even more predatory than the ones of half a century ago, even after decades of laws and regulations enacted to prevent racial discrimination in the housing market. “It was bad in the mid-20th century, but it is even worse now,” said Beryl Satter, a history professor at Rutgers University–Newark who wrote Family Properties, a book on the history of predatory lending in Chicago, about contract-for-deed arrangements. “The housing is in way worse shape, the markups are grotesque, and these people have been through multiple forms of credit exploitation, which is partially why they’re in this market.”

Through its lawyer, Harbour contested the idea that these contracts are exploitative. “It is simply not true that any of these agreements were predatory in nature,” David K. Stein, a lawyer for Harbour, told me. Instead, he said, contract-for-deed arrangements, which have been legal for centuries, give families who might not otherwise have the chance the opportunity to own a home.

Recommended: My Facebook Was Breached by Cambridge Analytica. Was Yours?

Contract-for-deed arrangements in today’s housing market came under scrutiny more recently in 2016, when The New York Times reported how low-income buyers in Ohio were entering into these agreements and then losing the homes. Soon afterwards, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau said it had assigned two enforcement lawyers to look into whether contract-for-deed transactions violate federal truth-in-lending laws. But now, advocates in Atlanta are raising another issue with contract-for-deed arrangements—alleging that they are racially discriminatory and that they violate the Fair Housing Act, along with various other state and federal laws. In a lawsuit filed in a U.S. district court last year, a group of plaintiffs represented by the Atlanta Legal Aid Society alleges that Harbour Portfolio, the group that owns the home where Zachary Anderson lives, specifically targeted African American neighborhoods with its contract-for-deed products. This violates the Fair Housing Act, the lawsuit argues, because it markets a predatory loan product specifically to African Americans. “Basically, what they were counting on is that people who were not already familiar with the home-buying process would be taken in by the American dream of owning a home,” Kristen Tullos, a lawyer for Atlanta Legal Aid, told me. Harbour moved to dismiss the case, but last month, a judge ruled that most of the plaintiffs’ claims in the case, including their core Fair Housing Act claim, could go forward.

Recommended: Why the GOP Is Making the Midterm Elections All About Impeachment

The Fair Housing Act, enacted exactly 50 years ago on April 11, 1968, makes it illegal to deny housing or loans to people in residential real-estate transactions on the basis of race. Subsequent cases have also found that targeting bad loan products at certain racial groups—a practice known as “reverse redlining”—also violates the Fair Housing Act. If contract-for-deed agreements are found by a judge to be aimed at African American neighborhoods, it will be evidence that the country has returned to the untenable position where it was half a century ago.

In the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans were prohibited from borrowing through traditional means, so they entered into contract-for-deed arrangements, which left them with little equity to pass on to their children. This had long-lasting effects—African Americans still have, on average, much lower credit scores than whites, in part because they didn’t have the means of building wealth through homeownership that whites had. In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, banks started lending more to African American buyers, but these buyers were frequently targeted by subprime loans with high interest payments and terms that were difficult to fulfill. (African American borrowers were 76 percent more likely than white borrowers to have lost their homes to foreclosure during the recession, according to the Center for Responsible Lending.) Now that many African Americans in cities like Atlanta were foreclosed on during the subprime crisis, many of them have bad credit as a result—which means they can’t buy homes the traditional way, and so are being offered contract-for-deed payments once again.

This tees up another cycle of debt and lost equity in the housing market, and in the larger economy that could continue to drag down the very people that the law 50 years ago had tried to protect.

Zachary Anderson has worked all his life, but he has never owned a home. For decades, he was a mechanic for the city of East Point, a predominantly African American suburb of Atlanta, making good money, but never enough to save up for a big down payment. This is not unusual: Black households overall have less savings than white ones, in part because of historical practices that prevented them from building equity. While the typical white household could replace almost 10 months of income if they liquidated all their financial accounts, the typical black household could replace only 23 days, according to a 2015 report from the Pew Charitable Trusts.

It was in 2010, while he was still working, living in a small apartment in the College Park area of Atlanta, that Anderson started seeing the signs around East Point. “SALE,” they read, in big red letters, and then listed the amounts buyers would have to put down—often as low as $700—and the amount they’d have to pay per month—often as low as $375—for the homes along the block. Anderson, sick of his cramped apartment and of hearing his neighbors’ every move, called the number listed on the sign and asked if they had any other houses in Atlanta. They referred him to a website that listed some of the homes, so Anderson went out and bought a computer so that he could start looking.

He eventually found a house he could afford in the Capitol View neighborhood of Atlanta, and the company gave him the code to a lock on the door that would enable him to get into the house and look around. The home, a small bungalow, was a fixer-upper. There was a hole in the roof, no stove or refrigerator, and tree branches invading the property. But Anderson knew how to work with his hands. He could put his own time and money into fixing up the home, he thought, which made it a good deal. The money he had to pay monthly, at $495, was less than he was paying in rent at the time. After a $1,000 deposit, he was told, the home, worth $46,750, would be his. (Harbour’s attorney declined to comment on the experiences of Anderson or any other specific individual.)

The contract, sent to him in the mail, also required that he paid all taxes on the property and kept the property insured. If he failed to make any of the agreed-upon payments, the contract said, he would forfeit all the money he had paid to the seller. He signed and initialed the contract in front of a notary, and sent it back to the company. A little while later, he received a letter in the mail congratulating him on becoming a homeowner. He could move in once he changed the locks, it said. He never met a single person from Harbour throughout the whole process.

Of course, it could be argued that Anderson should have known better than to enter into this type of contract, that he should have read the fine print. That he should have persevered until he could buy a home the traditional way. Harbour’s lawyer told me the individuals were provided “full disclosure” of the nature of the arrangement before they even first visited the homes. “It would be impossible for any reasonable person to not understand the nature of the transaction,” Stein said. But Anderson had never bought a home before. He didn’t know that this wasn’t the traditional way homes were sold. “I thought I went and bought a house,” he told me. He thought he had just stumbled across a deal.

He also didn’t know how difficult it would be to keep up the terms of the contract, because he didn’t realize just how much work the house would need. There is no requirement that a home inspector look at the house before a contract-for-deed agreement is signed. When Harbour told him he needed to get insurance, he says, the insurance company started sending him problems with the house that he didn’t even know existed—one document he showed me, for example, informed him that his “rake board,” which is a piece of wood near his eaves, was showing deterioration.

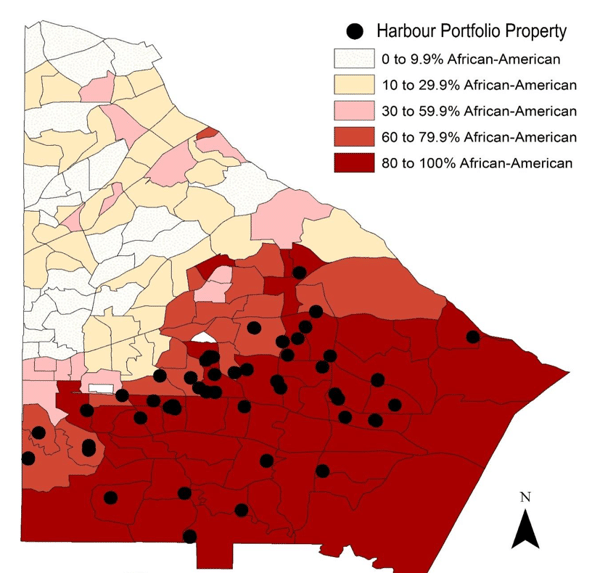

Harbour Portfolio Properties in DeKalb County, Georgia

There is nothing inherently wrong with contract-for-deed arrangements, says Satter, whose father, Mark Satter, helped organize Chicago residents against the practice in the 1950s. It’s still possible for sellers who aren’t banks to finance properties in a fair way, she said. A San Francisco start-up called Divvy, for instance, is testing a rent-to-own model in Ohio and Georgia that gives would-be buyers some equity in the home, even if they default on payments. But there are two reasons these contract-for-deed agreements seem particularly unfair, Satter said. First, the homes that many of these companies buy are in terrible condition—many had been vacant for years before being purchased, unlike the homes sold for contract for deed in the 1950s, which frequently had been left behind by white homeowners fleeing to the suburbs. Fixer-uppers make it even more difficult for would-be buyers to fulfill all the terms of their contracts, because the houses need so much work.

And second, Satter said, many of these companies are aggressively targeting neighborhoods where residents struggle with credit because of past predatory lending practices, such as those that fueled the subprime-mortgage crisis. “We’re watching private-equity firms coming in and cleaning up, finishing the job of destroying these communities,” she said.

In some ways, the concentration of contract-for-deed properties in African American neighborhoods is a logical outgrowth of what happened during the housing boom and bust. The lending market ran amuck, allowing banks to offer subprime loans and other financial products to people who otherwise might not have access to home loans. Often, these products charged exorbitantly high interest rates and targeted African Americans. One study found that between 2004 and 2007, African Americans were 105 percent more likely than white buyers to have high-cost mortgages for home purchases, even when controlling for credit score and other risk factors. When many of these people lost their homes, the banks took them over. Those that did not sell at auction—often those in predominantly African American neighborhoods where people with capital did not want to go—ended up in the portfolio of Fannie Mae, which had insured the mortgage loan. (These are so-called REO, or “real-estate owned” homes, because the lender possessed them after failing to sell them at a foreclosure auction.) Fannie Mae then offered these homes up at low prices to investors who wanted to buy them, such as Harbour.

But Legal Aid alleges that Harbour’s presence in Atlanta’s African American neighborhoods is more than happenstance. By choosing to only buy homes from Fannie Mae, the lawsuit says, Harbour ended up with homes in areas that experienced the largest amount of foreclosures, which are the same communities targeted by subprime-mortgage lenders—communities of color. Even the Fannie Mae homes Harbour purchased were in distinctly African American neighborhoods, the lawsuit alleges. The average racial composition of the census tracts in Fulton and DeKalb counties, where Harbour purchased, was more than 86 percent African American. Other buyers in the same counties that purchased Fannie Mae REO properties bought in census tracts that were 71 percent African American, the lawsuit says. Harbour also targeted its products at African Americans, the lawsuit argues. It did not market its contract-for-deed arrangements in newspapers, on the radio, or on television in Atlanta, the suit says. Instead, Harbour put up signs in African American neighborhoods and gave referral bonuses, a practice which, the lawsuit alleges, meant that it was mostly African Americans who heard about Harbour’s offer.

In its motion to dismiss the case, Harbour contests the idea that it targeted African Americans with predatory loans. Harbour’s practices of putting up “for sale” signs and encouraging people to refer friends to the company “are more accurately characterized as no marketing plan at all,” Harbour’s motion argues. What’s more, the process of buying up Fannie Mae homes and selling them on contract-for-deed arrangements does not immediately mean that Harbour was targeting a minority population, Harbour argues—in other words, Harbour is not the reason that so many of these homes were located in census tracts with large minority populations. “It’s not accurate that any one group was targeted,” Stein told me. Harbour bought homes from the government, he said, and didn’t have a choice where they were located. Additionally, he said, Harbour sold them “in a fair manner, and did so without any discriminatory or predatory practices or targeting.”

Still, Heather K. Way, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, told me that she thought Legal Aid had a “strong” case. Though the Fair Housing Act was initially aimed at prohibiting behaviors like redlining that prevent minorities from ending up in certain neighborhoods, a series of lawsuits in recent decades have led to another type of discrimination being prohibited under the law. “Reverse redlining,” for example, consists of marketing certain products to a protected class, like African Americans. In 2000, a judge found that a mortgage company had violated the Fair Housing Act by marketing unfair loans to African Americans in Washington, D.C. “Under the Fair Housing Act, you can’t intentionally target communities of color with these predatory lending products,” Way told me.

The contract-for-deed arrangements are predatory products, Legal Aid says. Harbour charges interest rates of around 10 percent, more than double the interest rates being charged for traditional mortgages, and it sells the homes for four to five times what it paid for them, the lawsuit says, even though the company does not invest money into fixing up the homes. The contracts are designed to fail, Tullos, the Legal Aid lawyer, said, because they require tenants to do so many repairs so rapidly.

Anderson’s contract, for example, required that he make his property “habitable” within four months. This turned out to be an expensive proposition. He repaired the roof, cut the limbs hanging over the house, repaired the sidewalk, and shored up the roof in the back where it was falling in, he told me. He installed a hot-water tank and bought a stove and refrigerator, he said. Since then, he’s also lowered the ceilings to retain some of the heat—his initial electricity bills were around $500 a month—put in a new fence, painted the house, replaced the windows, installed a new fireplace, put a screen on the porch, and added solar panels. He estimates that he’s spent $35,000 on the house. “It was just a really incredibly predatory contract in the way it was structured,” Tullos told me. “They transferred incredible burdens onto someone who was not actually a homeowner.”

When Anderson looked recently, he said, his Harbour account showed that he still owed the company $43,000, just $100 or so less than he’d owed in 2011, because such a high share of his payments go to interest.

Anderson was injured at work in 2012, and retired earlier than he’d expected, he told me. He now received disability payments of about $650 a month, he said. About $500 of those payments goes to Harbour, and the rest goes to the electricity company and the water company. He’s on food stamps and often has to borrow money from relatives in order to keep making payments on the house. When he was in the hospital after being injured and he missed a payment, Harbour told him it was going to evict him, he told me. But he caught up on the payments, and he’s determined not to let Harbour have the house back. He’s put too much work and money into it to lose it.

He is still current on his payments, but many of the plaintiffs in the Legal Aid case have fallen behind and are facing eviction. This is common in contract-for-deed agreements—nearly half of borrowers tracked over a 21-year period had defaulted and their contracts were canceled, according to a study prepared for the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs. Fewer than 20 percent of would-be buyers had actually received the deed to the property.

The Fair Housing Act was a long time coming. The Civil Rights Act, passed four years before, had outlawed discrimination in the workplace and in public facilities, and sought to end school segregation. But it had excluded language about housing, and discrimination in housing was still a pervasive problem even after that bill’s passage. Newly introduced fair-housing legislation was stymied by filibuster in 1966 and died in committee in 1967. It was not until the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. that President Lyndon Johnson had enough political capital to push a fair-housing bill through Congress.

In some ways, the Fair Housing Act allowed the country to make great strides in integration, implementing policies that sought to help families of color access high-opportunity neighborhoods and that helped create more affordable housing. But the long legacy of discrimination in housing means that there’s still a lot of inequality to overcome. The homeownership rate for African American households is now hovering around 42 percent, according to census data, compared to a white homeownership rate of 72 percent. “Ultimately, it’s not like we’ve taken real steps to stop predatory lending based on race,” Beryl Satter told me.

Americans are told homeownership is a pillar of the American Dream, yet it’s a dream that remains largely out of reach for certain groups of people. That’s why so many people like Zachary Anderson end up in these terrible deals. He told me that he doesn’t regret signing the contract with Harbour, even though he recognizes how unfair it is. He even says he’d sign the paperwork again, knowing that he would have to put thousands of dollars into the home and could still be evicted if he misses a single payment.

Despite the shock of learning that he isn’t actually the owner, he loves his little green house, and is still working on it, installing new flooring, painting the fence, fixing the shed. This initially surprised me—the contract for deed seemed like such a bad deal, why would anyone be willing to enter into such an arrangement knowingly? But Anderson likes having his own place to repair and fix, to style as he wants. He still dreams of the day he’ll own it outright—a friend won the lottery and paid off his contract-for-deed agreement, and Anderson hopes that will someday happen to him too. It’s the only way he could ever own a house. For Anderson, and many other people like him, even 50 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, a bad deal on a home is probably the only deal he’s going to get.

Read more from The Atlantic:

This article was originally published on The Atlantic.