How another president tried to hide his illness during a pandemic — and the disaster it created

This is part of an occasional series of Yahoo News articles and accompanying videos on how the issues America faced in the 1920s — aka “the Roaring Twenties” — have echoes in our own decade, a century later.

On Oct. 2, President Trump tweeted that he and first lady Melania Trump had tested positive for COVID-19 amid a surge of infections among the president’s White House staff and those close to him — and the world was shaken.

Questions loomed about what would happen if the president succumbed to or was incapacitated by the deadly coronavirus, which has so far killed more than 214,000 Americans and infected over 7.7 million others.

Yet the U.S. was plunged into further confusion as contradictory statements and information kept emerging from White House staff and the president’s medical team, with officials repeatedly dodging questions on everything from Trump’s lung scans to timelines on when the president had last tested negative for the coronavirus. Eventually the president’s physician, Dr. Sean Conley, admitted on Oct. 4 that he had initially downplayed the extent of the president’s illness in an effort to remain “upbeat.”

“I was trying to reflect the upbeat attitude that the team, the president, that his course of illness has had,” Conley said. “I didn’t want to give any information that might steer the course of illness in another direction. And in doing so it came off that we were trying to hide something, which wasn’t necessarily true.”

This isn’t the first time a president — and a White House — has contracted a deadly pandemic virus. And like the Trump administration, President Woodrow Wilson’s staff attempted to downplay the disease when Wilson caught the so-called Spanish influenza 100 years ago.

The first case of the Spanish flu within the Wilson White House was reported at the height of the pandemic in October 1918, but it was during a fateful trip to Paris that the president himself would fall ill.

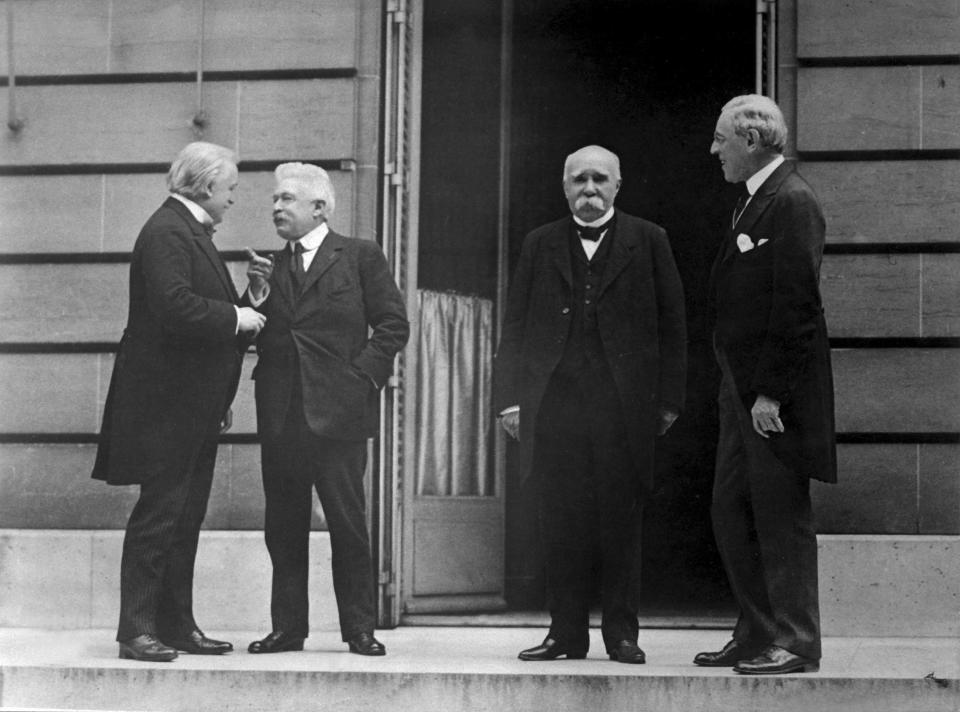

World War I ended on Nov. 11, 1918, but the following year the Paris Peace Conference would convene to discuss the future of Europe and important topics like the creation of a League of Nations and war reparations to be paid by Germany.

“Influenza was rampant in Paris at the time,” John Barry, author of “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History,” told Yahoo News. “It’s not clear if they were really taking any precautions. Probably not.”

For months, Wilson had downplayed the 1918-19 pandemic in an effort to keep morale and production high during the war, with no nationwide strategy to combat the pandemic. It’s an approach that was followed by many countries in Europe during the wartime effort; even the name “Spanish flu” is a misnomer — a nickname that stuck after Spain, which was neutral and had a free press, became the first to report on the pandemic.

In February 1919, multiple members of Wilson’s staff and family came down with influenza, including Secret Service members, the president’s chief usher, his stenographer and his eldest daughter, Margaret. And in April, in the middle of peace negotiations, Wilson himself fell ill.

Wilson’s staff and his personal physician, Rear Adm. Cary Grayson, tried to hide news of the president’s illness, saying he was merely suffering from a “severe cold.”

“The president has had colds of this sort from time to time,” the White House claimed to the New York Times on April 4, 1919, “and Admiral Grayson has always been able to combat them successfully.”

In reality, Grayson confided to a friend on April 14 that “these past two weeks have certainly been strenuous days for me. The president was suddenly taken violently sick with the influenza at a time when the whole of civilization seemed to be in the balance.”

Ultimately, their attempts to hide the president’s condition failed.

“They asked everybody to keep it quiet,” Barry told Yahoo News. “But there were too many people who knew.”

Even when Wilson was no longer bedridden, the effects of the Spanish flu were difficult to conceal. Neurological complications were a common feature of the 1918 virus — and of other influenza viruses, including COVID-19. Its toll on Wilson was noticed by everyone in Paris — from Wilson’s closest aides to other foreign leaders including David Lloyd George, the English prime minister, who remarked on Wilson’s “mental and spiritual collapse” during the conference.

“His mind was affected,” Barry said of Wilson. “It was noticed by everybody immediately. A level of paranoia; he thought he was being spied on by the French. Some crazy thinking; he thought he was personally responsible for every piece of furniture in the entire American delegation. Something about automobiles bothered him, even though he wasn’t going out. I mean, it was bizarre.”

“It probably affected his performance,” Barry added. “Prior to his illness, he was insistent upon the principles that he said that America was going to war to defend … and he caved in on every single thing after he got sick, except for the League of Nations. But everything else he gave away.”

Many historians believe that the resulting treaty, which was harshly punitive toward Germany, laid the groundwork for the rise of Hitler and World War II.

Despite a brief hospitalization for COVID-19 only a week ago, including taking therapeutics remdesivir and the steroid dexamethasone, President Trump has been eager to quickly resume robust, large-scale campaign events. On Saturday, Trump gave a speech to hundreds of guests from the White House balcony — his first public event since testing positive for the coronavirus. The president also tweeted that he will be in Sanford, Fla., on Monday “for a very BIG RALLY!”

“Saturday will be day 10 since [Trump’s] Thursday diagnosis,” Conley said in a Thursday night press release, “and based on the trajectory of advanced diagnostics the team has been conducting, I fully anticipate the president’s safe return to public engagements at that time.”

On Saturday, Conley cleared the president to return to an active schedule.

But Dr. Uché Blackstock, a Yahoo News medical contributor and CEO of Advancing Health Equity, cautions that the disease has an unpredictable course and potential long-term complications.

“What it’s known for is this fluctuating course where people start feeling better and then they start deteriorating,” Blackstock said after Trump’s discharge from Walter Reed hospital last week. “And we also know that people have symptoms for weeks, if not months, and so I think it still remains to be seen how this president will do.”

The long-term effects of COVID-19 are still being studied, but so far there’s evidence of the virus’s impact on the lungs and heart months after infection, including heart muscle damage even for patients who experienced mild COVID-19 symptoms. Coronavirus is also known to cause brain-related conditions in patients even when they haven’t been hospitalized in intensive care units, including confusion, trouble focusing, changes in behavior and stroke.

Wilson’s own encounter with the Spanish flu would continue to affect him long after his April 1919 ordeal in Paris. In September, during an aggressive speaking tour of the U.S. to promote the formation of the League of Nations, Wilson collapsed, with what Grayson described as “nervous exhaustion.”

In a formal statement, Grayson said, “The trouble dates back to an attack of influenza last April, in Paris, from which he has never entirely recovered.”

The rest of the tour was canceled, and days later Wilson would suffer a stroke — another medical incident that would be shrouded in secrecy, with Grayson and Wilson’s wife, first lady Edith Wilson, running many of the White House affairs themselves. With his health continuing to decline, Wilson would be largely debilitated for much of the remainder of his presidency, which ended March 4, 1921.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: