Hurricane Ian destroyed his house. Still homeless, he's facing near-record summer heat.

LINDEN, N.J. − Javier Velez has been homeless ever since Hurricane Ian blew the roof off his Fort Myers, Florida, home and filled it with more than 4 feet of water in September 2022.

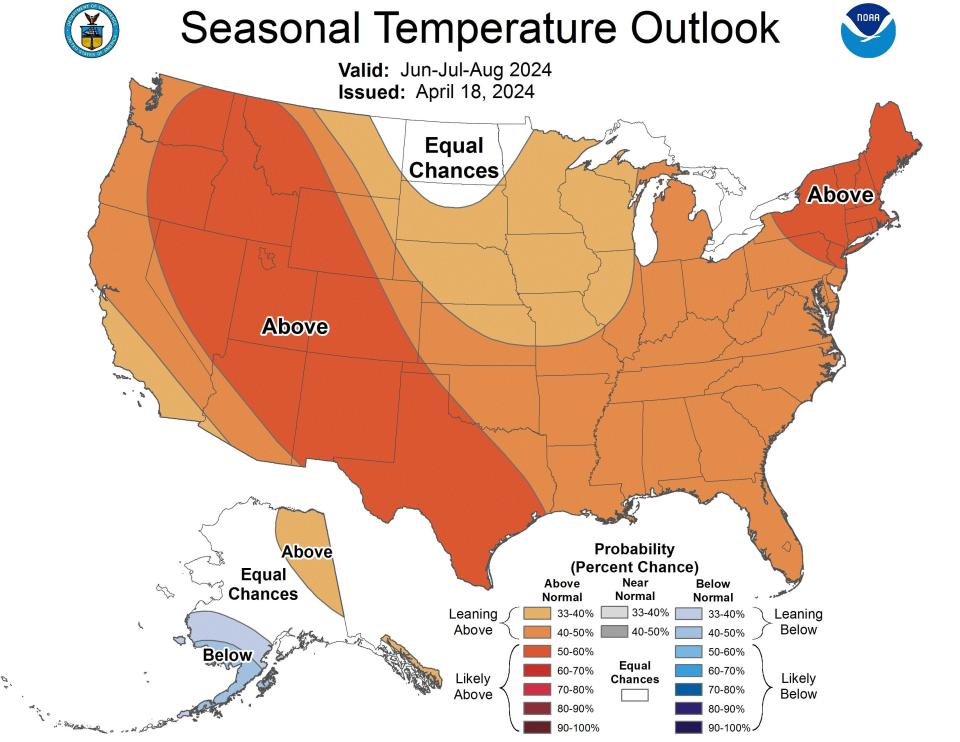

This summer will be his second living without proper shelter. His work as a truck driver brought him north to New Jersey in May, and with summer forecasts predicting unusually hot temperatures in the northeast, he'll likely face sweltering conditions for weeks in June, July and August.

Forecasters warn hotter than average temperatures this summer, which officially begins near the end of June, will take a heavy toll on unhoused populations − which include many low-income people who lost housing to wildfires and hurricanes and remain homeless like Velez. Nationally, more than 250,000 unhoused people live on the streets, in vehicles, or other spaces unfit for human habitation, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

"People without shelter who are subjected to extreme heat are very vulnerable," said Jeff Masters, a meteorologist with Yale University.

In New Jersey, Velez will cook and bathe in his truck cabin.

"I'm probably just going to park under trees and keep the doors open to stay cool," Velez, 60, said in an interview in Spanish.

After natural disasters, some never return home

Velez is one of millions of Americans who have been displaced by natural disasters in recent years, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2023, more than 3 million people experienced displacement due to events like hurricanes, flooding, wildfires and tornadoes, the bureau found.

"It's just so devastating to see everything you've done, everything you've worked so hard to accomplish, and then it just gets destroyed," Velez said.

Hurricane Ian, a massive Category 4 storm, destroyed more than 5,000 homes and buildings in Lee County, Florida, where Velez lived, according to the National Hurricane Center. Ian's path surprised meteorologists when the storm veered away from Tampa, Florida, and crashed directly into southwest Florida. The storm was the third-most costly U.S. hurricane on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, leading to the deaths of 156 people in Florida, North Carolina and Cuba.

More than 15% of natural disaster survivors never return home, according to a report from the Urban Institute. In 2023, about one-third of those whose home was damaged by a natural disaster were searching for new housing for more than one month, the social policy think tank found.

Low-income people have a harder time recovering from disasters because they may have fewer belongings to begin with, and are less likely to have their homes insured, according to disaster recovery advocates.

“Natural disasters increase income disparities," said Caryn Wheeler, executive director of the Jackson County Community Long-Term Recovery Group in southern Oregon, where wildfires have in recent years destroyed thousands of units of low-income housing.

Velez said he can't cobble together enough money from savings or insurance claims and FEMA disaster relief funds to fix his home − especially the roof, which needs to be replaced.

"No one is helping me," Velez said, explaining that his roof insurance claim keeps getting rejected.

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season begins on Saturday and goes through Nov. 30, peaking in September. Meteorologists warn record hot ocean temperatures in the Caribbean mean there's an 85% chance of above-average hurricane activity this year.

"We have the most aggressive forecast ever issued this early in the season for a bonkers hurricane season in the Atlantic," Masters said.

In Oregon, wildfires destroyed affordable housing

While much of the U.S. could face above-average temperatures this summer − including parts of Oregon and California − this year, the region will likely be safe from drought conditions, and the wildfires they bring, Masters said.

But in 2020, that wasn't the case.

In Jackson County, Oregon, 18 mobile home parks full of cheap housing units were destroyed by the September 2020 Almeda Fire, according to Wheeler. Many of the units were 50 years old − or more − and were worth very little, having depreciated from their purchase price of $20,000 to $30,000, according to data from Wheeler's organization. In many cases, residents owned their units and rented the land they sat on.

When the Almeda Fire reduced Tania Pineda's $5,000 mobile home to ashes, she and her family moved into an RV park created for survivors employed by the local hospital. Her family had lovingly restored the unit, but didn't get an insurance policy.

Because some affordable housing options, like mobile homes, are worth so little in the housing market, it's practically impossible for residents to rebuild new homes for a cost equivalent to what their old homes were insured for, according to Wheeler.

“These are households for whom their entire stability went up in flames," she said.

Three months after her home was destroyed, Pineda learned she was pregnant with her second child. During the summer of 2021, while pregnant, she endured temperatures she said peaked around 108 degrees in the tiny RV. Her mattress was right next to her living room which was squished next to the kitchenette, she said. The RV's storage area, meant to hold an all-terrain vehicle, was her 4-year-old daughter's room.

"I'd sit down and just cry," Pineda, 28, said. "I would cry when my daughter would nap. I would cry − just the toll of knowing that this might be my life for the next couple years was hard."

After Pineda gave birth in August 2021, she and her two children moved in with her parents, where she still lives, in Medford, Oregon.

Pineda said she hopes to move out later this year, but it will depend on how quickly she receives assistance from wildfire recovery programs. Her family is on stage three out of a seven-stage process that's "very slow-moving," she said.

Velez, who has been in New Jersey for less than a month so far, said he plans to return to Florida by December with more money in hand from truck driving jobs in and out of Linden.

Hotter summer forecast for Northeast

New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts and other states in the northeastern corner of the country are expected to be hotter than average this summer.

"I think it's going to be a top-10 warmest summer on record for the northeast since 1970," Masters said, estimating the region's largest city, New York, will see nearly 30 days with a high temperature above 90 degrees. Each summer the city has an average of 18 days with temperatures reaching that high, Masters said.

New York City has an unhoused population of about 88,000 and New Jersey has around 10,000, according to HUD.

"The homeless are extremely exposed because there's no way you can recover from the heat you experience during the day," said Raquel Silva, a researcher at ICF Climate Center, a global consulting firm focused on climate crises and affordable housing.

Forecasts show the Northeast could also have a wetter summer than average, he warned, driving up humidity and making the heat feel hotter.

In New York City and Newark, New Jersey, asphalt and a lack of grass and trees in urban environments will also make summer heat feel hotter, Masters said. Meteorologists refer to this as the urban heat island effect, he said, noting "it particularly rears its head at night."

"Cities are much, much hotter at night than the surrounding countryside," Masters said. "If you don't have a chance to cool off, then you're going to see a long period of stress, and that's been shown to increase heat illness when you don't cool off at night."

More extreme heat also increases the likelihood of power outages caused by everyone using their air conditioners at once, overwhelming energy infrastructure, Masters said. Around the country, about 8 million low-income people are exposed to extreme heat waves and that can negatively impact energy systems, according to a new report from ICF.

"You've got these cooling centers, but what if the power goes out?" he said, adding that people who lack transportation will also have a harder time accessing air conditioning.

Deadly heat in the Southwest

This summer, the Southwest will be even hotter than the Northeast, with forecasters warning west Texas through New Mexico, Arizona and Utah will also likely face higher-than-average temperatures.

"My main area of concern is the southwest U.S. − that's where NOAA has placed their bull's-eye for where the most intense heat is expected to occur," Masters said.

Phoenix will likely experience temperatures that are above what Arizonans are used to, Masters said, and the consequences could be more deadly than in years past, he warned. Last summer, the average temperature in the Phoenix area was 97 degrees, representing more than a 4% increase from the average temperature during the summer of 1970, according to the nonprofit Climate Central.

The increasing temperatures have mirrored a rise in heat-related deaths in the city. Adults aged 50 and older, people living in mobile homes and people experiencing homelessness suffered more from the extreme heat in recent years, according to the department.

Arizona public health officials said there were 645 heat-related deaths in the Phoenix area in 2023, a nearly 50% jump from 2022, which saw 425 heat-related deaths. Both years saw higher numbers than 2021, which had 339 heat-related deaths, the Maricopa County Public Health Department said.

Further north, in Chico, California, average temperatures peaked at 106 degrees during the summer of 2018, according to data from the National Weather Service.

That November, the devastating Camp Fire destroyed Sara Stewart's home, where she had been living with her children and her parents. Afterward, she and her boys lived in their car and in campgrounds for more than five years, she said.

During the winter, she traveled with her boys to Texas, Arizona and New Mexico, working odd jobs at gem shows and other seasonal events. When it got too hot in those places during the summer, they'd camp in north California and Oregon, she said.

The 33-year-old single mom's family finally got into their own home in April, she said, with the help of a housing program for fire survivors in Chico. She lives in town now, further away from the areas that are more at risk of fires. She's still paranoid, she said, but also more prepared for emergencies. Through it all, Stewart said she's more aware than ever of how people become homeless for different reasons.

"Unfortunately, through the public eye, homelessness is lumped together as we're all the person in the tent doing drugs," she said. "But it's circumstantial."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Heat waves in summer 2024 will be dangerous for homeless