'I hope that it doesn’t get as bad as it did in Canada': Ex-public servant on Trump's anti-science stance

Scientist Max Bothwell just wanted to talk about “rock snot.”

Reporters were asking the Environment Canada employee about the “snot,” a freshwater algae, he’d been researching. But the then-Conservative federal government would only allow him to do a live CBC Radio interview if a communications person could listen in on the line — a condition neither Bothwell nor the CBC would agree to.

“I did what I was told to do,” Bothwell, now retired from public service, told Yahoo Canada News about relaying the interview request to a centralized communications office. “They said it was okay for the CBC to phone me and do a live on-the-air interview, but Ottawa wants to be on the line listening in while the thing was being broadcast to the Canadian public — without the Canadian public knowing about it.”

The kind of muzzling that he and other federal scientists experienced under Stephen Harper’s government should be expected in the United States now that President Donald Trump is making his positions clear, Bothwell says.

On Tuesday, the Trump administration introduced new restrictions on scientists and others in tech, engineering and math (STEM) fields doing work under the federal government.

The government ordered a temporary media blackout on the Environmental Protection Agency, where it also froze new contracts and grants. And the Huffington Post reported that similar orders had been given at sub-agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institutes of Health.

As well, it was reported by BuzzFeed Tuesday that U.S. Department of Agriculture employees had been restricted from publicly sharing summaries of scientific papers, tweets, and other “public-facing documents.” After public backlash, BuzzFeed reported Wednesday that the USDA order had been rescinded.

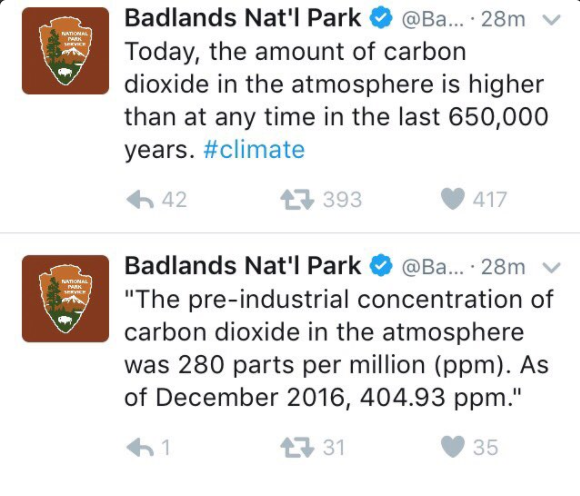

On Tuesday night, someone with the Badlands National Park in South Dakota appeared to go rogue, tweeting several scientific facts about climate change from the park’s official Twitter account. A National Park Service spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that the account had been compromised, and the tweets came from a former employee.

The crackdown under this administration was not entirely unexpected. In December the Washington Post reported that scientists were copying U.S. climate data because of fears it would be erased when Trump took office.

And it’s not without precedent. The restrictions placed on U.S. federal agencies brings to mind policies from the Harper era here in Canada.

“I’m not surprised at all,” Bothwell said. “These people, Harper and Trump, are cut from the same cloth.”

Harper’s government restricted media access to federal scientists by requiring them to go through a media manager if contacted by a reporter. Reporters often had to first talk to a government public-relations employee before they could be granted an interview with the scientist they sought.

Sometimes requests were denied, or a written statement would be provided by email in lieu of a telephone or in-person interview.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberals dropped the requirement for scientists to go through a media manager when they took government in 2015.

The Harper government’s handling of scientists harmed Canadian science, Bothwell says. “The integrity of Canadian science was questionable during those years,” he said. “Everyone, all of my colleagues in the United States, knew what was going on.”

Canadian spending on research and development also declined for three years in a row from 2013 to 2015, according to government data.

Overall Canada’s science community was damaged, says Alana Westwood, a scientist with the Boreal Avian Modelling Project and leader of the national research program of Evidence for Democracy, a non-partisan advocacy group that supports evidence-based government decision making. Data that was lost in cancelled programs or the termination of the long-form census cannot now be reconstructed, Westwood says.

The group grew out of the Death of Evidence rallies held around the country in 2012, Westwood told Yahoo Canada News. Action like attending rallies and protests can help, she says, and demonstrate public support for scientists.

“Join rallies, join protests, support organizations like the Union of Concerned Scientists,” Westwood said.

In the U.S., a group is now planning a protest march in Washington, D.C. and at other cities, inspired in-part by the Women’s March.

“This is a non-partisan issue that reaches far beyond people in the STEM fields and should concern anyone who values empirical research and science,” the Scientists’ March on Washington site reads.

As for the scientists themselves, Bothwell says that many of them will be hamstrung by the need to hold onto their jobs or their funding and will find themselves in the same position many Canadian scientists felt they were in under the previous government.

“What do I tell them? You gotta wait four years or find some other place to work,” Bothwell said, adding that many Canadian scientists chose the latter option. “I hope that it doesn’t get as bad as it did in Canada and I guess we have to really wait and see how this plays out.”