'I'm actually here, despite what I went through': Nunavik initiative shares stories of perseverance

Saachipikinuukwau Bobbish was 12 when she had to call youth protection services on her own family.

As the eldest child, she had been caring for her six siblings — with the littlest as young as three months — while her parents struggled with alcohol addiction.

"I said 'that's enough,'" said Bobbish. "I was tired."

"I couldn't do anything. I had no income. I was still in school. I didn't know how to feed my siblings," she recalled. "My parents didn't really give me the attention or the love and the care that I needed as a child."

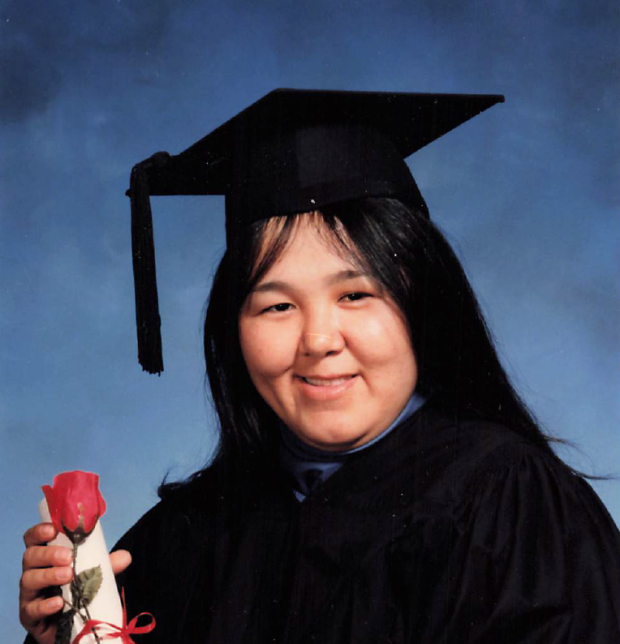

After youth protection services stepped in, Bobbish, who is half Cree and half Inuk, bounced around from foster home to foster home until she was 18 — when she made the decision to give back.

"As soon as I turned 18, I started working for youth protection as … an emergency social worker," said Bobbish, who lives in Chisasibi, Que.

For eight years, Bobbish has turned her situation around and used the experiences she went through to help serve her community and begin healing her own "inner child."

She shared her story as part of an online initiative called Ajuinnata, an Inuktitut word that means let's keep moving or let's keep it up. In its third year, the project is organized by Esuma, a group made up of several regional organizations, and coincides with school perseverance days to celebrate resiliency in Nunavik.

For the past few weeks, Inuit have shared their personal stories online — posting about how they have overcome challenges including addiction, raising children on their own, dealing with intergenerational trauma or deciding to go back to school.

'Expressing yourself can be medicine'

Sylvia Cloutier, one of the project's organizers, is from Kuujjuaq, Que., and says perseverance is inherent among Inuit.

"Our ancestors survived the harshest climate in the world … [We're] able to navigate through a lot of hardships and a lot of difficult conditions," she said.

Cloutier says the project is about much more than education. It's about showcasing the successes of people who are from Nunavik.

Encouraging people to post online on a Facebook forum and nominate those they know who have persevered, she says it has become a safe space for Inuit to talk about hardships.

"Everyone has a story. Everyone has overcome hardships in their own way, and everyone has their own experiences that they've learned how to push through," said Cloutier. "It was about creating an opportunity for people to open up if they wish to do so … for somebody who perhaps wouldn't be accustomed to sharing their story."

She says when Inuit hear each other's stories they can "see ourselves in others."

"We get to see people in a different light when they share their story," said Cloutier.

"Also just to normalize expression … I know that sometimes expressing yourself can be medicine so I just wanted to be a part of a movement."

Born in an igloo, she persevered to go to college

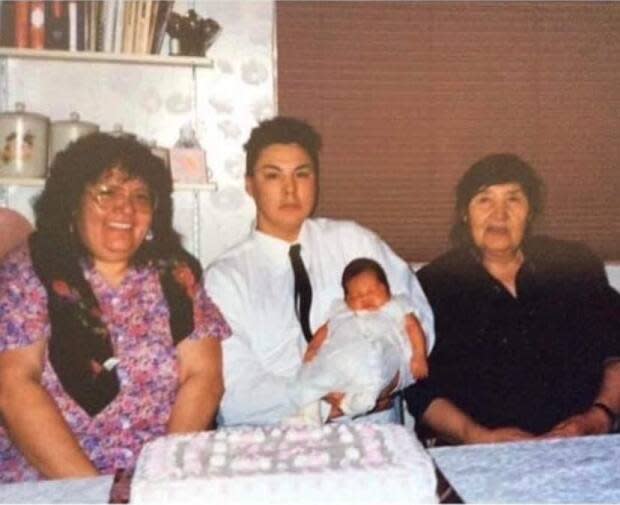

Melinda Eva Hickey says it's important for younger generations to hear the stories of resilience from their elders to show the community that "we can make it through in life."

Hickey shared the story of her mom, Alasie Kenuajuak Hickey, on the forum.

"I thought my mom was a very good role model … She was one of the last generations that were born in igloos," said Hickey.

"And now it's 2023 and she's on Facebook. She is on the internet. She Is proof that you can persevere from living off the land to [using] all the technologies."

Hickey says her mother was touched when she heard her daughter posted her story online. She said her mother is very humble, despite overcoming several challenges throughout her life before attending college and taking university courses.

When she was a child, her mother lost her father to the tuberculosis epidemic and when she was 15 she was sent to Ottawa to attend federal day school, said Hickey.

"That was a culture shock for her as well, to be away from her mother, from her culture, from her country food. That was extremely challenging for her."

"She adapted to whatever situation she's in … [When she returned to Nunavik] she brought back the knowledge that she learned from her schooling. She brought it back to her community and her family … in a positive way."

"It's extremely important to share these kinds of stories. Especially with the generation[s]... [She is] just one generation above myself, so I think it's still amazing that these kinds of people they're living with us."

'I'm actually here, despite what I went through'

Winnie Mickeyook, vice-principal of Asimauttaq School in Kuujjuarapik, Que., posted her story in the hopes of inspiring students and reminding them they are not alone.

Mickeyook grew up in Kuujjuarapik in a family that suffered from alcohol addiction. She recalls feeling like her mother's addiction was her fault.

"I despised her. I would always say 'I'm not going to be like her,'" said Mickeyook. But when she moved to Montreal for school and work, she too developed an addiction.

"Maybe it's because of the trauma I went through growing up … I knew when I started drinking [that] I had totally no control."

When she got sober, Mickeyook vowed to never return home.

But 16 years later, her mother was sick and needed someone to accompany her for treatment.

"I decided that I was going to go back … I started to get to know my mother and why she drank," said Mickeyook, adding that her mother apologized just the day before she died.

"She asked to meet all my siblings and … she apologized to us," said Mickeyook, with a sob.

"That's where it blossomed [and I] let go of the past and accepted it and forgave her. It was the best thing that I had done for myself and my mother."

Mickeyook shared her story online in the hopes of inspiring generations of Inuit, reminding them they are not alone and how they can persevere despite difficult situations.

She says sharing stories of trauma and perseverance can help facilitate healing, as it did with her when she attended treatment in Oka, Que. years ago.

"At the treatment centre, this is the first time where I would share what happened with me growing up and it was the first time I was able to talk about how I felt and where I came from," said Mickeyook.

"Each time I would share it, I would start crying. It was the only way for me to let go of what I held on to for a long time… I met other people like me and I didn't feel alone anymore."

In her role as a vice-principal, she now hopes to be a resource for children at her school who might be going through similar situations.

"It's mind-boggling sometimes, like, I'm actually here, despite what I went through," said Mickeyook.

"I'm just here waiting for a student to come and talk to me and open up … Even if I touch one student, that's wonderful, but to have more than that, you know, that would be a miracle."

Forgiveness and moving forward

Reflecting on the past eight years, Bobbish says she learned to forgive her parents, who are now sober, understanding how residential school had scarred her father.

"I was only 26 or 27 years old when I finally understood why my upbringing was like that … I only understood my upbringing because of the graves, the unmarked graves were discovered [at former residential schools]," said Bobbish.

Throughout her healing journey Bobbish says she often thought back to her great-grandmother who gave her her Cree name. She now thinks it's particularly apt, given her journey and the sense of hope she hopes to share with others.

"My Cree name — Saachipikinuukwau — it means the first spring flower as it starts to bloom," said Bobbish tearfully.