The impossibly cool story of Lawrin, the 1938 Kentucky Derby winner from Kansas City

Far from the madding crowd, here lies Lawrin — the brown colt with four white socks who was lucky to be born at all and bred in the Kansas City area largely because of fortune ... and who implausibly in every way won the 1938 Kentucky Derby.

The improbability of both his nearby birth and final resting place in a placid Prairie Village cul-de-sac is an apt reflection of the indulgences of fate that enabled a moment trumpeted on the front page of The Star as “IT’S ‘OUR’ DERBY.”

At the subtle yet striking monument to Lawrin and his sire, Insco, on a grass island in the middle of the circle, there were zero other passersby in a nearly 30-minute period on Wednesday. The only audible noises were chirping birds, the occasional bark of a dog and a U.S. flag and rope clanging on a flagpole adjacent to the wrought-iron fence around the headstones.

The hushed, dignified setting was in stark contrast to the pomp and “decadence,” as Hunter S. Thompson famously put it, that was sure to again seize Churchill Downs on Saturday, when some 150,000 people were expected to attend the 149th Derby.

And it was a galaxy away from May 7, 1938, when Lawrin became the first and only locally bred horse to win the Derby — and one of the most charming and underappreciated underdog tales I’ve come across.

Perhaps the story of Lawrin, who was bred and owned by clothing retailer and horse aficionado Herbert M. Woolf, is familiar to you.

But in 10 years here, I’d never heard of him until my friend Ben Warner of Prairie Village casually made mention of him. So I started to read up and quickly became enthralled with all the unlikely aspects of Lawrin’s journey, which was stunning in itself but also a springboard to the legendary futures of jockey Eddie Arcaro and trainer Ben Jones.

By a late twist after a near-fatal injury to the jockey who had been riding Lawrin and Arcaro’s preference to ride another horse, Arcaro rode Lawrin to the first of his five Derby triumphs, a record matched only by Bill Hartack. And Lawrin was the first of six Derby winners trained by Jones, the Parnell, Missouri, native whose record was equaled only by Bob Baffert.

But those landmark careers will forever be entwined with their first breakthroughs.

Despite infinite factors that made it preposterous — including the mere existence of Lawrin.

“Chance, ruler of racing, smiles at Kansas City,” led one of The Star’s multiple stories the day after the Derby.

A $500 investment

Founded by Herbert Woolf’s father and uncle and enhanced when Woolf took over in 1915, the Woolf Brothers operation would become “one of the Midwest’s classiest and most successful men’s clothier’s,” as described in a Missouri Valley Special Collections biography of Woolf.

But Woolf also was passionate about horses, beginning with riding and ranching during an extended stay in Arizona as a youth sent there to recuperate from an illness.

He made a hobby of showing horses before becoming disillusioned with that world: He felt cheated out of a state-fair prize as he determined one judge was a part-owner of the winning horse.

“He wanted to be where the horse that stuck his nose out and finished first was first,” Alfred Lighton, the nephew of the life-long bachelor, told The Star in 1987.

So Woolf turned more towards racehorses in 1929 and to the training of Jones and son Jimmy in 1931 — the year that Insco finished sixth in the Derby. He began purchasing thoroughbreds for breeding and racing, and he built a track on his 200-acre Woolford Farm that featured bluegrass and white wooden fences in what is now Prairie Village.

(While Lawrin generally is understood to be a native Kansan, the farm straddled the Missouri state line. So there remains some question as to where he was conceived and born. J.A. Felton, a cousin of Jimmy Jones and attorney at Lathrop GPM, said Jones considered Lawrin a “Kansas City horse.” And wherever he was conceived and foaled, he surely trained and grazed on both sides of the border. The only other horse from either state to win the Derby was Elwood, from Maryville, in 1904.)

As his interest intensified, Woolf in 1933 set out for an auction in Lexington intent on purchasing Insco, whose bloodlines made him coveted despite reports he had been hobbled by training injuries.

The day after the 1938 Derby, the International News Service put it less delicately: Insco actually had suffered a broken leg that would have led most veterinarians to euthanize him; Lawrin thus was “fortunate to even be alive.”

Still, Woolf only was able to purchase Insco for $500 because he had arrived early and “escaped being blocked by a cloudburst that tore at bridges and blocked traffic,” The Star reported. With only one “cash-in-hand customer” in front of him, the auctioneer reluctantly accepted a bid that was a fraction of the horse’s value.

Later that night, Woolf was offered $7,500 for Insco and declined.

“And am I glad,” he said after the Derby victory three years later.

Tender-footed and gluttonous

Insco was mated with Margaret Lawrence and on Jan. 30, 1935, begot Lawrin — a fusion of their names.

By disposition and early performance, anyway, his future was inauspicious. As described on the American Classic Pedigrees web site, Lawrin was “a gluttonous eater who required a lot of work to stay fit” and had a “fractious” personality.

But trained by Jones, Lawrin in 1938 won four races and finished in the money in all eight races before the Derby.

Even so, uncertainty loomed over his ability to perform in the Derby.

To protect what The Star called his “tender feet,” Lawrin was in 10-pound bar plates in his previous two races and still wore high white bandages on his front legs as he was being saddled on Derby day.

So Lawrin, one 1938 report said, might as easily have “spread himself like a bed sheet in two strides” that day.

“That horse was never completely sound,” Lighton said in 1987. “It had a problem that was common: a tendency to have bowed tendons. They never bowed, but that is why they raced him so selectively. They could tell that if they ran the horse too much, he would break down.”

Meanwhile, he suddenly was being ridden by a new jockey.

Only weeks before, Sammy Roberts, Woolf’s contract jockey who had regularly ridden Lawrin, fell from his mount at Oaklawn in Arkansas and was severely injured and unconscious for days. He recovered at least well enough to attend the Derby as Woolf’s guest, but the jockey-to-be remained uncertain until the final days.

Arcaro was under contract to another stable that didn’t have a horse in the Derby. But he vacillated about riding Lawrin because he initially had wished to ride Menow, another Derby horse, according to news reports from the era. Ultimately, though, he signed on with Woolf and Ben Jones, who suggested walking the track early the morning of the Derby.

In the foreword to the book, “In The Winner’s Circle,” Arcaro wrote “I learned a few things that proved valuable that afternoon, and Ben was right as usual.”

A four-leaf clover

Before he left for the Derby that morning in Louisville, Lighton told The Star, a neighbor walking her dog found a four-leaf clover and gave it to Woolf — who put it under Lawrin’s saddle pad before the race.

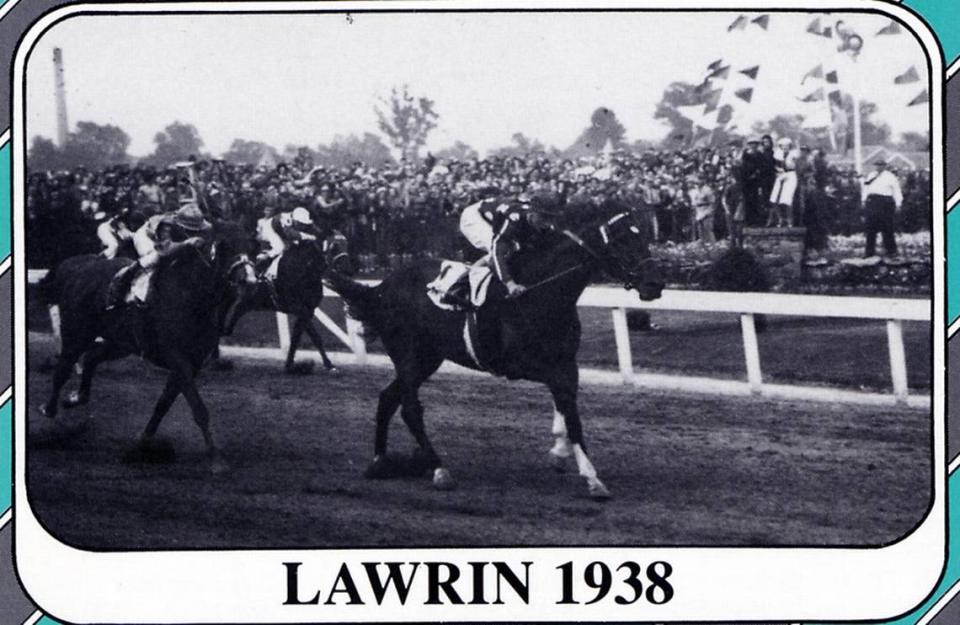

It didn’t seem to be a factor at the starting gate, though, where Lawrin began in the No. 1 post position at 8-1 before an estimated crowd of 60,000.

Phrasing varied in accounts of what happened, including one that said Lawrin broke through the stall gates four times. But one way or another, he clearly delayed the start with his antics and was in fifth place at the first turn.

But with Arcaro whipping him furiously — which I cringe to write — Lawrin worked his way to the lead before he was swerving with what seemed to be exhaustion down the stretch.

The Bloodhorse, though, wrote that Arcaro later told Woolf he almost blew the race because he thought the finish line was in front of the new presentation stand in the infield.

Somehow, after all the bizarre zigs and zags and oddities along the way, it was Lawrin by a length over Dauber.

Afterward, wrote Time magazine, Woolf “was so elated that he pranced like one of his colts, swung his binoculars above his head in circles and pumped Arcaro’s hand again and again.”

Alas, the career of the horse who won more than $100,000 for Woolf that year proved fleeting. It ended two races later when a tendon issue rendered him unable to continue.

That fleeting time frame, though, is part of the story of a supernova — who died in 1955 and was buried on the farmland sold that year.

And even from his remote and serene final resting place, Lawrin still represents a phenomenon you could hardly make up … and one to be remembered.