Inglewood highrises the latest battleground in struggle between development and preservation

It was 1973 and Inglewood was facing a paradox.

There was a plan to "turn the tide of urban blight and make Inglewood a safe, pleasant place to live," Gary Park, a reporter at the Calgary Herald, wrote in January of that year. But the community, Calgary's oldest, had to first go through a rebirth.

Architect Jack Long mobilized the community around the plan to guide its future — which would fight off the city's intentions for the wrong kind of development (paving the neighbourhood over for a freeway) in favour of the right kind (multi-unit complexes that would bring in new residents).

But in a city opposed at the time to high-density housing, Park wrote, Long's plan to save the then-shrinking neighbourhood urged a near-doubling of its population.

And plans for Blackfoot Trail and Bow Trail freeways, "once responsible for so much anguish within the community," would offer the greatest relief to reduce traffic along the "worn, decaying" Ninth Avenue.

It involved tough conversations, activism, debate. The movement won over then-mayor Rod Sykes, who defended the neighbourhood and its residents' vision, Park wrote.

Park noted it wasn't the first time the neighbourhood faced a threat.

"By 1934, the area was on its way to extinction. A city general plan that year coloured Inglewood in sinister, industrial hues, which were repeated in 1960."

Today, if you walk through Inglewood, you'll see preserved sandstone and brick buildings along what was Calgary's first main street, so picturesque that they've appeared as historical backdrops for TV shows like Fargo.

The red paving stone sidewalks are shadowed by mature trees, and lead visitors to local gems like an arcade bar, an independent bookstore, a mid-century furniture shop. As that description indicates, it's also increasingly gentrified, with some debate over how well the old phrase "KISS — Keep Inglewood Slightly Sleazy" still fits.

But keep walking, and you'll spot banners reading "Save Ninth Avenue."

That's because Inglewood is facing more development that could set a precedent for the community's future.

Three building proposals are on the horizon for Ninth Avenue S.E.

All three, if built, would be more than double Inglewood's current height limit of 20 metres (65 feet). The fight over that height limit isn't new, either — residents have been protesting one proposed highrise after another, as recently as 2018.

If you ask the local community association, the buildings represent a "slow creep" of modern developments that could overshadow the street's heritage character. The developers position their applications as bringing in fresh architecture and boosting business by increasing density.

"I think that's an ongoing battle in inner-city and more mature communities," Sasha Tsenkova, a director with Heritage Calgary and an architecture and planning professor at the University of Calgary, said of the push-pull between development and preservation.

"It's not just the history but also the built form that's the result of waves of evolution, and that creates the special attachment to the place and makes it way more significant," she said, adding that "when we preserve history, we actually make history."

"It's a long-term goal that we have, it's not a project-specific goal or intervention. It's about landscapes, it's about places that have a complex and evolving identity, and we are really stewards of those places. We need to make sure that they transition over time and we can provide these assets to the next generation."

The first proposal, Rndsqr Block, was approved by city council last week.

It's a 12-storey (45-metre) mixed-use building that would blend a boutique hotel with apartment living, co-working spaces and main-street retail shops, behind a twisting, contemporary, transparent grid. It would replace a car dealership while preserving the historic Bank of Commerce building next door.

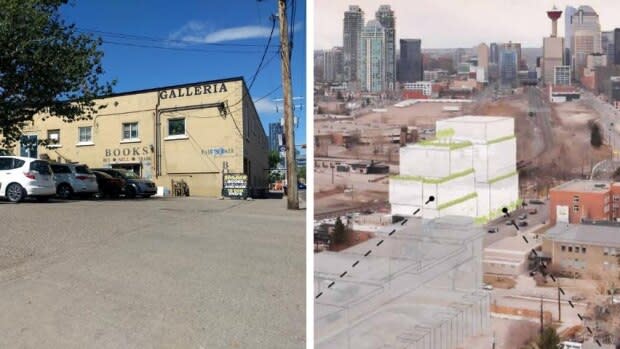

The second, Edison from Hungerford Properties, would replace the cinder block building that's currently home to the Fair's Fair bookstore with an 11-storey mixed-use building. That's been approved as well.

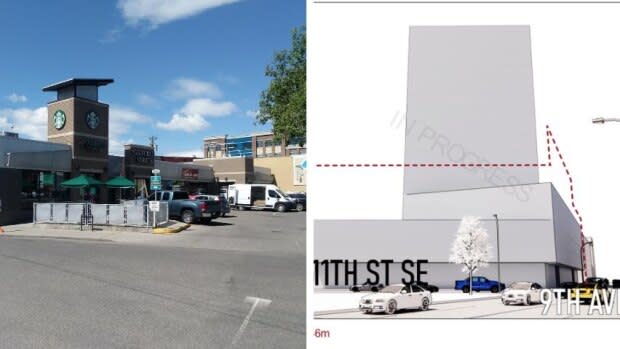

And the third, Louis on Ninth from Landstar, would replace a strip mall and parking lot with a mixed-use tower rising 50 metres (164 feet) above the pavement.

Both Louis and Edison incorporate some form of setbacks to keep the total height of the buildings off the street.

A petition against the three developments, organized by the community association, has garnered more than 30,000 signatures.

"The question is how to move forward in the face of these proposals that are absolutely controversial because they are historic changes in the fabric of a historic community," said Coun. Gian-Carlo Carra, a few weeks before council's vote on Rdsqr.

Carra said he felt Inglewood used to be gripped by somewhat of a "suburban Stockholm syndrome," with the idea that the neighbourhood shouldn't change.

"I think people sort of quickly realized that … no, that's actually not what this neighborhood is really about … we saw the redevelopment, the ongoing change in the neighborhood, as potentially adding heritage today that would be celebrated deep into the future," he said.

Carra said the neighbourhood is seeing the results of a push for better planning — public investments are reinvigorating the community, and the private sector is responding.

But he said he doesn't feel the current leadership of the community association is connected to that mission.

"There are those who believe that Inglewood was bequeathed to us perfect by the heritage gods and any change is blasphemy, and they are potentially working to minimize the damage of change rather than drive the best possible changes," he said.

"Sadly, we we've been scratching the surface as we teach our planning department to have these forward looking conversations and as we spar with community interests … [who] actually want to minimize change because they view change as deeply problematic."

L.J. Robertson, with the Inglewood Community Association, told the Calgary Eyeopener in early July that Carra treats himself as a "planning messiah."

"It's most unfortunate that Coun. Carra has just forgotten that he is, after all, a civil servant. We find his position to be a little insular," she said.

Phil Levson, also with the community association, said the group is in favour of development if done right.

"This is not a case of NIMBY. It's a case of best practices in urban planning that fit with the community," he said.

"You can preserve and grow," he said. "But the three [developments] that are currently proposed … do not fit with the image or the ambiance that we currently have."

'Age-old conflict'

Tsenkova said urban planning discussions become even more complex when heritage elements are involved, and that there needs to be a sensitive dialogue between the old and the new — both in terms of balancing design and conversation.

"It's important to create an atmosphere and a dialogue of good understanding, and it is important to respond to the pulse," she said. "It's rare for all these groups to align but building consensus is important."

Beverly A. Sandalack, a professor of landscape architecture and planning at the University of Calgary, has been at the table for plenty of those conversations through her work with Urban Lab.

The University of Calgary research group is described as an "ongoing experiment in education, research and outreach."

"It's the age-old conflict between people who want to keep things exactly as they are, which is kind of impractical, because evolution can be really good as long as it's done right," Sandalack said. "Good streets and good neighbourhoods are sometimes victims of their own success … eventually things will get redeveloped."

Sandalack said discussions around the future of communities remind people that while urban evolution is inevitable, getting involved can help influence the quality of that development — like ensuring a tall building has a positive relationship to the street on the ground level, through wide sidewalks, trees and subdividing that allows for multiple entrances.

"If people come at it with a preconceived notion or these polar opposites of thinking, it's not very productive," she said.

Sandalack said one place where discussions can often get bogged down is by focusing on architectural style, which is hard to resolve as it's a matter of taste.

Instead, a good common talking point can be a focus on the quality of street life, which can be achieved together through both contemporary and historical characteristics.

And Inglewood's main street is special. That's one point where everyone agrees.

"I think that Calgary, in the boom and bust cycles of its evolution, has lost a lot of heritage resources," Tsenkova said.

She said those heritage spaces shouldn't be preserved as museums, but their uniqueness should be enhanced by any new developments — and those metrics, however nebulous, need to be maintained.

"I think that is something that if you lose it, it's really difficult to come back," she said.

"There really aren't all that many good streets in Calgary. There's way too few for a city of our size," Sandalack said. "When somebody comes to Calgary, you'll probably take them to one of those streets."

Calgarians will immediately know the spots Sandalack is referring to.

Kensington. 17th Avenue S.W. Stephen Avenue. Fourth Street S.W.

Ninth Avenue S.E.

The debate around the street's future is ongoing.

Sandalack suggested another piece of common ground to begin that discussion, at least in terms of one of the proposals.

"Putting a building on that corner is way preferable to a car dealership."