Islanders urged to watch for sick and dying creatures as 3rd summer of avian flu begins

P.E.I. residents are being asked to keep an eye out for sick and dying birds and animals as a third summer under the threat of avian flu draws near.

The virus subtype H5N1 was first seen on the Island in March 2022, when a case was confirmed in the tissues of a bald eagle found on P.E.I.'s North Shore.

By May of that year, 23 birds had tested positive, as well as four fox kits that had a preliminary positive test for avian flu.

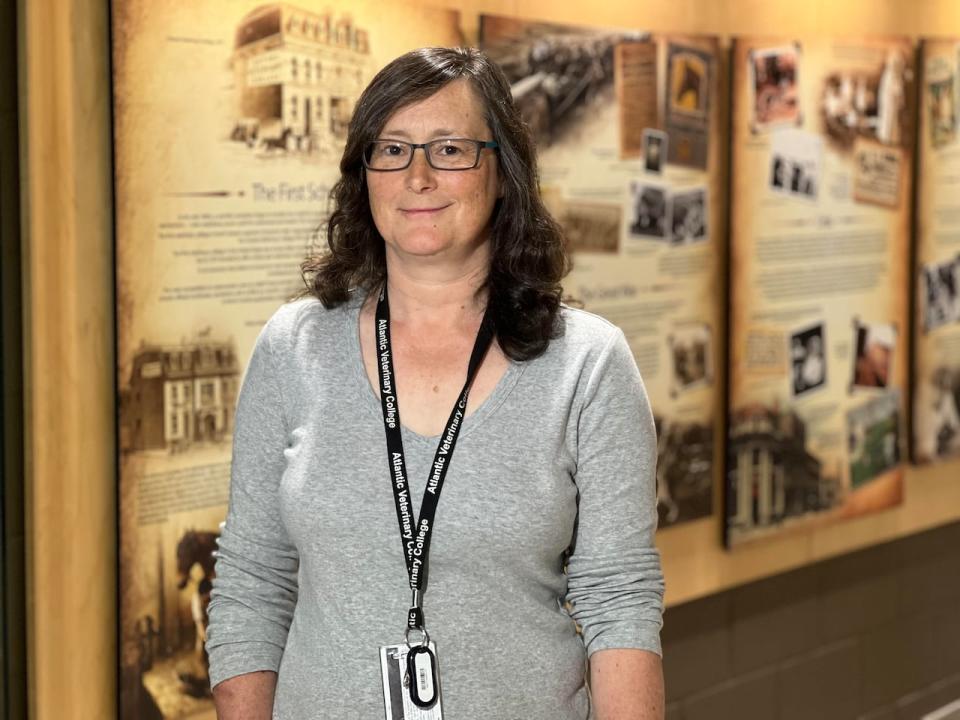

"We're still getting a handful of positive wild animals from P.E.I. every month," said Megan Jones, regional director of the Atlantic region of the Canadian Wildlife Health Co-operative, and an assistant prof at the Atlantic Veterinary College in Charlottetown. "Anywhere from three to five animals per month have tested positive so far in 2024, for example."

Still, Jones said the lab is getting fewer submissions now, so there may be less disease and mortality related to the virus. "But certainly it's still around, and we're still detecting [it] regularly in dead wild animals."

Jones said the birds most commonly affected tend to be crows and Canada geese. They also had a snowy owl test positive this winter.

"Raptors can get infected — red-tailed hawk, eagles occasionally," Jones said.

"Over the winter, we had quite a few skunks test positive as well, the odd raccoon, and most recently, we've been getting positive foxes."

A dead northern gannet is shown on the beach at Basin Head in northeastern P.E.I. in June 2022. (Nicola MacLeod/CBC)

Jones said many of mammals tend to be carnivores, so they are infected as they eat the carcasses of birds that had avian flu.

Most birds are infected from direct contact, or being close to each other. Some eat the remains of other birds, though, including eagles. As scavengers and predators, they often eat dead Canada geese.

Jones said it's important for Islanders to report sick or dead wild animals so that researchers can test them, but she warns people not to approach such wildlife, let alone touch them.

Birds and mammals all tend to get neurological signs. The virus goes into their brain and so they behave strangely.

— Megan Jones, Canadian Wildlife Health Co-operative, Atlantic Region

"These animals, if they do have bird flu, they will be behaving strangely.

"Birds and mammals all tend to get neurological signs. The virus goes into their brain and so they behave strangely. They may just not run away from you. They may be having seizures.

"For those animals, what we want people to do is to report them to Fish and Wildlife, or to our office, and we can help co-ordinate getting them tested, because we want to make sure we're keeping tabs on the virus."

Could be something else

Jones said it's also important to test to make sure they're not missing other potential causes of the animals' symptoms, including rabies.

Megan Jones is an assistant professor at the Atlantic Veterinary College as well as regional director of the Canadian Wildlife Health Co-operative's Atlantic region. (Rob LeClair/CBC)

"We don't typically have rabies in P.E.I., but it was detected recently, last September, in a bat on the Island," she said. "We definitely want to continue testing these animals to, number one, keep tabs on the avian flu virus, but also to make sure we're not missing something else."

Jones said there were high mortality rates in the summer of 2022, particularly in migrating sea birds.

"In P.E.I., we were seeing it very commonly in northern gannets, which had just come back for the summer. And those animals really suffered from some large-scale mortalities," she said.

"They gather closely together in densely packed colonies. There's no social distancing at all and they seemed to be very susceptible to the virus at the time."

A fox is seen feeding her kits in Belfast, P.E.I. Jones says carnivorous mammals can become sick from eating the remains of birds that were infected with the avian flu virus. (Shane Ross/CBC)

Compared to that summer, she said, "we are not seeing as wide-scale mortality."

Jones said it's hard to predict how long avian flu will be around.

"It's considered to be endemic in some populations, which means it's just circulating within the animals and it doesn't seem to be going away," she said.

"So it could stick around; it could taper off. Really, there's no way to tell."

Poultry owners remain vigilant

P.E.I.'s chief veterinary officer is also keeping a close eye on the avian flu situation this summer.

"Now that migration has more or less taken place, most of our bird species that come back for the summer have done that," said Dr. Jill Wood. "We're not seeing an increase in reports of positive birds right now, compared to what we have been seeing."

Dr. Jill Wood is the chief veterinary officer for the province of Prince Edward Island. (Aaron Adetuyi/CBC)

She said they are still seeing "the odd one here and there, for sure."

Wood said Islanders in the poultry industry should remain vigilant about the potential spread of avian flu from wild birds.

"Certainly our poultry industry is continuing to be very aware of that," she said. "We're continuing to encourage all our poultry owners… to prevent contact with wild birds, because it is still present, although it does seem to have calmed down compared to say two years ago."