Jerrod Carmichael Said Three Words to Me That I Think About Every Day

“This show is a strange way of trying to make it work,” Jerrod Carmichael told me about Jerrod Carmichael Reality Show and its role in repairing the emotional chaos that exists within his own family. “But it is with the optimistic intention. It is with the intention of healing.”

In episode 5, “Jamar,” Carmichael takes a break from trying to heal himself and his family and turns his attention on trying to heal his best friend and his family. Carmichael tries to do this by sharing what he’s learned about vulnerability and radical honesty and the truth-telling properties of stand-up comedy, and what we all learn together is: that shit is not for everyone.

Jamar Neighbors and Carmichael go way back in stand-up, as it turns out. It was Jamar who, upon seeing an early open-mic performance, gave Carmichael a lesson that he has clearly taken to heart: “You’re funny,” Jamar told him, “but slow down a little.” Jamar does not seem to take his own advice; his stand-up is rapid-fire, punctuated with literal back-flips. When it is slow and patient, it’s in service of concepts like, “Here’s my impression of Spider-Man taking a shit.” Jamar is going to have a tough time getting personal. (Unless he is in fact Spider-Man, which I would believe; my guy is jacked.)

Jamar and Carmichael were also roommates back in the day, something Jamar talks about on-stage by way of saying that, when Jerrod came out, their mutual friends jumped right to the assumption that Jamar was gay too, or at least that something physical must have happened between them. As a gay man, I went from “I can’t believe those kinds of conversations are still going on among our straight male friends” to “Of course they are” with a speed that was honestly startling.

Carmichael knows Jamar has trauma from his childhood; Jamar’s mother had to give him and his sister up to foster care for a few years, and he has never seen a photo of his father. So Carmichael makes him an offer: “Come on the road with me, and let me direct you.” Right away, we can tell Carmichael wants Jamar to do what Carmichael himself does: use comedy as an especially candid therapy session. Jamar calls it out: “I don’t want to do therapy comedy,” he says. “Jeff Bezos is going to space, why am I gonna talk about my foster mama?” Carmichael answers perfectly: “Jeff Bezos is going to space because it’s some things he can’t talk to his mama about.”

So they give it a go. Jamar gets into some uncomfortably personal spaces on stage, but just as quickly, he deflects with a joke or a big laugh or a back-flip. This is going to be a process, and—for the reasons big-name stand-up comedians ask you not to use your phone and tape them when they’re working out new material—it’s not entirely fair to show the world in this early and fragile stage.

Jamar is uncomfortable about it, so he brings it up with Marvin. (“Who’s Marvin?” An audience member asks. “The therapist Jerrod is making me go to,” he answers.) “Can you be a victim of something,” he asks his therapist, “and then not have a victim mentality about it?” Marvin, whose face is not shown and so immediately I trust him, says he believes so. Jamar says he asked that because he sees Carmichael crying on stage and suggests it’s evidence of a victim mentality. This is all cut together with footage of Jamar working out, which let’s be honest, is a lot of guys’ way of crying.

Back on stage, Jamar gives another try to being totally open and vulnerable and improvisational and occasionally quiet, and the audience reacts by being constantly quiet. A few people get up to leave. “You leaving? I get it, I’m nobody,” he says. In a conversation afterwards, an audience member Marvins it up on the topic of trauma: “We normalize things that are not normal,” she says, “but that doesn’t mean they don’t have an effect on us.”

Jamar comes to this conclusion: “You have the right to say you hurt me, but I love you,” and although he goes into some painful details about his mother not coming to his high-school graduation like she’d promised, he backpedals: “If she hadn’t done that, I probably wouldn’t have had the balls to come to Chicago and do bitch-ass therapy.”

We meet Jamar’s mother—whose apartment is Live Laugh Love’d up—and the aunt and cousins who helped raise him, and it’s obvious they’ve all caused him a great deal of pain, and it’s equally obvious that he hasn’t processed it. A man in this world has two choices, this episode seems to say: he can be honest and upset the status quo and be accused of being stuck in a victim mentality (and/or, regardless of the man’s actual sexual orientation, gay) or he can keep it pushed down and take it to the gym.

The options for men are clearest in the climactic scene, in which Carmichael brings Jamar with him to a park to fly a kite. “I’m not flying a kite with no gay [n-word],” Jamar protests. He gives it a half-hearted go after a lot of pressure, but ultimately, Jamar cannot be as gentle and unself-conscious as one has to be to keep a kite in the air. But he does try to do a series of back-flips across the park. Kite or back-flips are our choices.

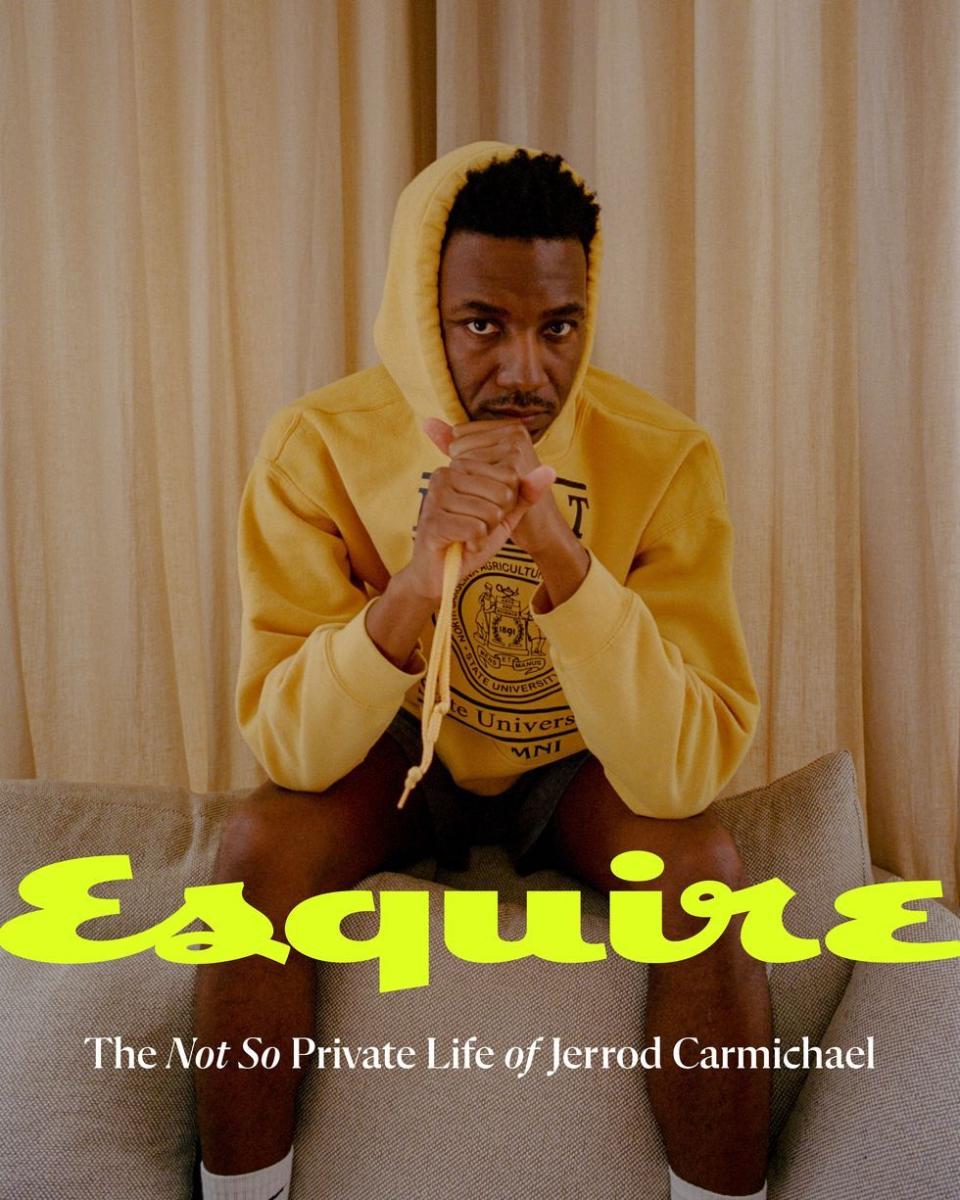

Carmichael and I talked about the kite scene when I spoke to him last month. As a man, he said, “you're raised just to not do what the girls do in any way. It’s hard to shake the idea of that as weakness, to evolve beyond that, because it's instilled. It becomes second nature, and I definitely had those fears.” He told me a joke he’s been telling friends: “I came out of the closet and started smiling in pictures,” and I said “Exactly” so loud my Apple Watch gave me the excessive noise warning. “I was doing a lot of the masculine hand gestures, the tight fist and the other hand over it,” he continued. “Because men don't know what to do with their hands. And I just wasn’t smiling.”

I agreed. I've been through it. To appear masculine, and therefore not gay, which for some of us is a thing we feel the need to do in order to survive, we spend some of our lives feeling a pressure to throttle everything that’s exuberant or joyful about us. I said as much.

“Yeah,” Carmichael replied, followed by three words that I’ve thought about every day since: “Joy is gay.”

He laughed, and I laughed. When people say men are in crisis right now, this is the shit they're talking about.

Keep Reading:

You Might Also Like