Jokowi Bets Indonesia Legacy on Prabowo Winning Vote Next Week

(Bloomberg) -- President Joko Widodo is making a gamble on his preferred successor winning Indonesia’s election in one round, even as the wager risks dividing his supporters, denting his credibility and curbing the influence he has built in the past decade.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Haley Loses Nevada Primary to ‘None of These Candidates’ Option

China Replaces Top Markets Regulator as Xi Tries to End Rout

The leader known as Jokowi is betting on Prabowo Subianto winning outright on Feb. 14, as he’s anxious the defense minister could lose if there’s a June run-off poll, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named speaking about private discussions.

The large number of swing voters is also worrying Jokowi as his backing along with ample funding should have garnered Prabowo above 50% support, which hasn’t happened, the people said, citing internal surveys by the campaign teams. Public pollsters have showed that the ex-general and former son-in-law of the late dictator Suharto was closing in on at least 50% support — which is required to win the election.

In a few days, some 205 million Indonesians will cast their votes. Then, Jokowi will find out whether his gambit — which has fractured his cabinet, burned bridges with his own party and split his loyal followers — will pay off to let him wield influence long after he steps down in October.

While Jokowi’s approval rating is still hovering around 80% as of a late January poll, some key personalities who helped him win the presidency have turned against him. They were disappointed by his bold moves to secure his legacy, including allowing his son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, to become Prabowo’s running mate.

The cult rock band Slank that wrote Jokowi’s campaign jingles over the past decade is backing another candidate. Academics are urging him to remain neutral or step down, while activists who once supported him now see him as undermining democracy. Even his close ally and longtime friend Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a former governor of Jakarta who stood by his side before he became president, has turned away.

“What Jokowi did destroys the very basic rules of democracy,” said Amalinda Savirani, a political analyst at Gadjah Mada University. “Many of his supporters feel betrayed, deeply.”

Representatives for Jokowi didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment. On Wednesday, the president called for neutrality and said he won’t campaign at the final rally this weekend.

“Prabowo and Jokowi are best friends,” said Habiburokhman, vice-chairman of Prabowo’s Gerindra party. Prabowo won’t betray Jokowi and he will continue the president’s policies, he added.

Jokowi, who hasn’t publicly declared his support for Prabowo, has denied trying to create a political dynasty, and has dismissed reports of rifts within his cabinet.

Still, his backing became evident when his son became the defense minister’s running mate. Jokowi said in a Jan. 24 speech, with Prabowo standing by his side, that the president is allowed to take sides and campaign. The two men have held multiple private meetings since late 2022.

“What everyone is saying about how Jokowi is building his political dynasty cannot be denied,” said Jay Octa, a former Jokowi supporter who’s decamped to volunteer in another presidential candidate Ganjar Pranowo’s campaign.

The president roused furor when his son’s path to becoming a vice-presidential candidate was cleared by a Constitutional Court ruling presided by Jokowi’s brother-in-law, who was later dismissed for that ethical breach. It’s the first time in Indonesia’s history that the scion of a sitting leader is contesting for one of its top two offices.

A soft-spoken former furniture-maker and Metallica lover, Jokowi came to power a decade ago as an outsider promising to reform a political system dominated by family dynasties and military elites. Time Magazine put him on the cover with the headline: ‘A New Hope.’

But the country’s track record for governance weakened during his tenure. Last year, Indonesia ranked 115th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, worse than when he took power. His administration passed a sweeping criminal code criticized as an attempt to stifle free speech and curb dissent. His move to bring the anti-corruption body under the president’s office eroded the agency’s independence — a turnaround for a man who campaigned on stamping out graft.

Economic Powerhouse

Jokowi believes he is the one who can turn Indonesia into an economic powerhouse, according to people close to the leader who have accompanied his rise from mayor of Solo to Jakarta governor and later president. He wants the country to break out of the middle-income trap before an aging population takes hold. That requires the right successor to continue his plans, or his efforts would go to waste, they said.

Under his rule, Indonesia became one of Southeast Asia’s success stories. His export bans forced companies to refine resources like nickel onshore, pushing the country up the global value chain and boosting investments to $47 billion last year. That’s nearly double from when he took office.

He has built more than 2,000 kilometers (1,242 miles) of toll roads over the past decade, equal to the drive from New York to Miami. Leaders before him only built 780 kilometers over 40 years.

“It is naive to think that policies are made just for the greater good,” said Achmad Sukarsono, a Singapore-based associate director at Control Risks, with a focus on Indonesia. “I believe that he truly wants to see a better Indonesia with better public infrastructure and services for the masses that love him and he belongs to. At the same time, he has personal ambitions to leave lasting legacies and protect the wellbeing of his family. That by itself does not mean he is undemocratic.”

Succession Plan

Jokowi has thought deeply about policy continuity since he first became president in 2014 and has been crafting a succession plan for years, according to people familiar with the matter.

He did consider extending his tenure beyond the maximum two terms and had begun gathering support within parliament to amend that constitutional limit, said the people. But the president — who believes in polls — was discouraged by the high disapproval rating in an internal survey conducted by his team. His party leader Megawati Soekarnoputri was also against a term extension.

Indonesia put in place that term limit in 2001 to avoid a repeat of Suharto’s three-decade rule marked by forced disappearances and rampant corruption.

Last year, Jokowi looked to former Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo as his protege and heir apparent, seeking to pair him up with the popular Prabowo. That plan unraveled when he saw that Ganjar was more easily influenced by Megawati than himself, the people said. So Prabowo became his next option, they said.

To hedge against Prabowo balking at continuing his policies, Jokowi positioned his own son Gibran to campaign alongside the ex-military general. That made Jokowi the first president to back a candidate from a different political party, dividing the ruling party PDI-P while raising the specter of conflicting interests that could disrupt policymaking.

Market Jitters

“It is extremely likely that there will be competing agendas, and little guarantee that Prabowo will continue to adhere to Jokowi’s policy preferences after he is elected,” said Edward Aspinall, a professor at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs in Australian National University.

Investors are already pricing in political risk ahead of the election, said Aditya Sharma, a strategist at Natwest Markets. That’s especially after Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati and other ministers were said to weigh resignations, uneasy with what they saw as Jokowi’s election-meddling.

The jitters are showing. The rupiah slipped 2.5% against the dollar last month, the most since October.

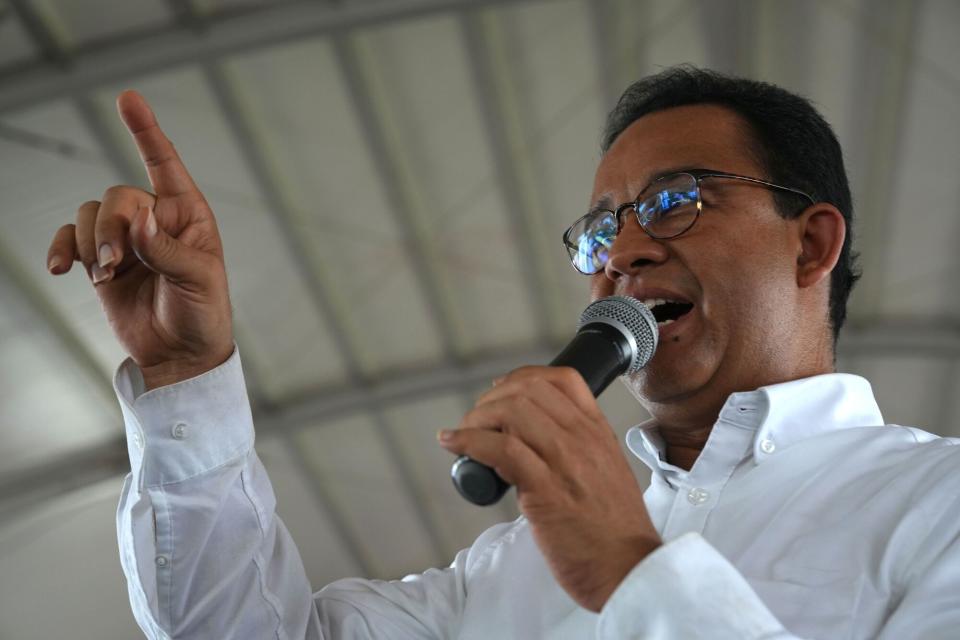

Then there’s the potential that the other presidential contenders — former governors Anies Baswedan and Ganjar, who is backed by PDI-P — could join forces in the event of a run-off.

Jokowi is already preparing backup plans, including the possibility of making amends with PDI-P. As an act of reconciliation, he sent Megawati birthday wishes on Jan. 23 along with her favorite flowers: purple orchids and baby’s breath. But for Megawati, Jokowi’s support for Prabowo was a betrayal of the highest order, the people said.

“Don’t be afraid of power because power doesn’t last,” she said at a PDI-P event on Jan. 18, in what observers interpreted as a veiled jab toward Jokowi.

Enduring Legacy

The ruling party remains split. Megawati’s daughter Puan Maharani, who’s currently the speaker of parliament, doesn’t want to end up as opposition and is more open to working with Prabowo’s coalition and staying on friendly terms with Jokowi, the people said.

Representatives for PDI-P didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Jokowi’s transformation from the humble political outsider to a brash member of the elite is something that the president’s aides have confronted him with, said the people close to him. Jokowi dismissed their concerns, they said.

“By tying his future fate to Prabowo, a political ally who became a rival and then an ally again, Jokowi is taking a risk to try to ensure an enduring legacy in Indonesian politics,” said Ben Bland, director of the Asia-Pacific Programme at Chatham House who wrote Jokowi’s first English-language biography.

“Once the president leaves the palace, their power and influence typically declines very rapidly and Jokowi wants to avoid that situation,” he added.

--With assistance from Chandra Asmara, Matthew Burgess and Kevin Dharmawan.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.