‘Journalism is not a crime’: Joe Biden backs Evan Gershkovich, US journalist jailed in Russia a year ago

Joe Biden said he is working “every day” to secure the release of Evan Gershkovich, a jailed Wall Street Journal reporter the US president said is being held by Russia as a “bargaining chip”, as the journalist marked one year behind bars.

Mr Gershkovich, 32, became the first US journalist arrested on spying charges in Russia since the Cold War when he was detained by the Federal Security Service (FSB) last March during a reporting trip in the city of Yekaterinburg.

Despite being a fully accredited journalist, he was accused of spying for the US by the Russian authorities – an accusation that he, The Wall Street Journal and the US government vociferously deny.

His plight has sparked global uproar and concerns about the collapse of press freedom in Russia. It was even raised by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, on Thursday, when the primate called for the world to pray for Mr Gershkovich over the Easter weekend.

“Journalism is not a crime, and Evan went to Russia to do his job as a reporter – risking his safety to shine the light of truth on Russia’s brutal aggression against Ukraine,” Mr Biden said in a statement, vowing to work to free Mr Gershkovich and other US citizens locked up in Russia.

He added: “We will continue working every day to secure his release. We will continue to denounce and impose costs for Russia’s appalling attempts to use Americans as bargaining chips.”

No one knows exactly how many US citizens are being held in Russia. Another American accused of espionage is Paul Whelan, a corporate executive from Michigan who was arrested in 2018. He was sentenced two years later to 16 years in prison, on charges he also denies.

US secretary of state Antony Blinken condemned Russia’s actions, saying that in the last year, its already restrictive media landscape has become more oppressive and its authorities are targeting “any form of dissent”. He called for the immediate release of both men.

“To date, Russia has provided no evidence of wrongdoing for a simple reason: Evan did nothing wrong. Journalism is not a crime. People are not bargaining chips,’ he added.

One year on from his arrest, Mr Gershkovich has not stood trial, nor have the Russian authorities revealed any details of the accusations or any evidence to back up the charges, his friends, families and colleagues say.

Instead, he is being held in pre-trial detention in a tiny cell in Lefortovo prison in eastern Moscow – and his confinement was extended by another three months on Tuesday. He has already made a dozen or so appearances in court, where his incarceration has been extended repeatedly.

Holding a huge banner reading “Free Evan” in front of the Brandenburg Gate in the German capital Berlin, the journalist’s close friends said they believe he is being held as a bargaining chip by Russia.

“It is unimaginable. Lefortovo prison is designed to break people and cut them off from the outside world. He spends 23 hours in his cell. It’s amazing he is still strong,” said Francesca Ebel, a close friend and the Russia correspondent for The Washington Post, who told The Independent she communicates with Mr Gershkovich via letters he writes from his jail cell.

“Part of his arrest was designed to crush what was left of journalism in Russia. It has had a very chilling effect,” she added.

Pjotr Sauer, another close friend and the Russian affairs correspondent for The Guardian, said Mr Gershkovich keeps himself busy replying to at least 5,000 letters that have come in from well-wishers across the world. He said Evan also plays chess with his father and friends via mail.

“The world should not forget Evan. He was doing a public service by reporting on what was going on in Russia, shedding light on a country which is so hard to understand,” he told The Independent at the gathering. “It is not just about our friend, it is about press freedoms.”

Mr Gershkovich’s plight has drawn worldwide attention and cast a searing light on the lack of free speech in Russia, where the president, Vladimir Putin, has tightened his iron grip on the country, including securing a landslide victory a few weeks ago in a stage-managed election with no serious competition.

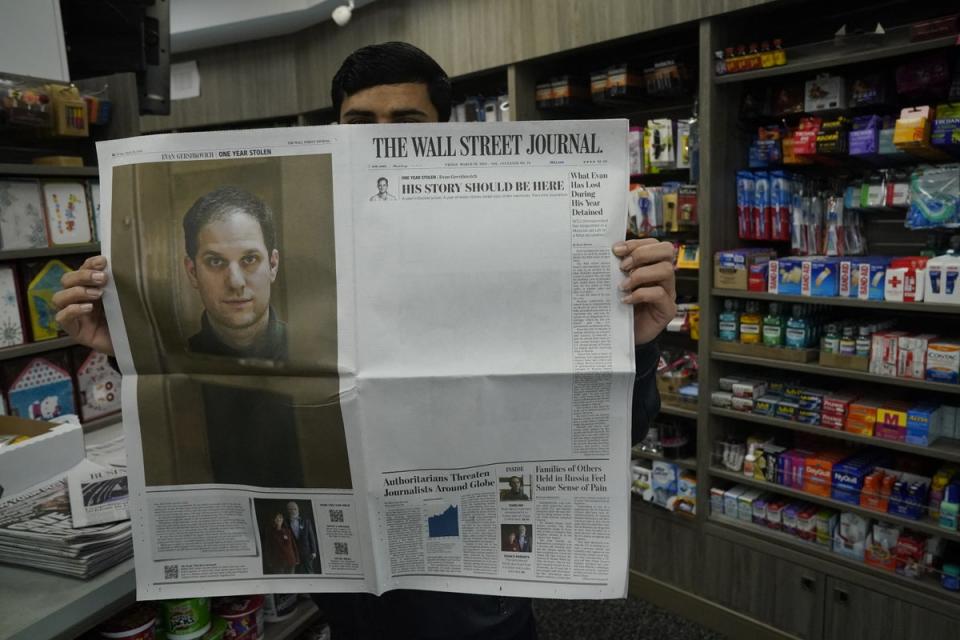

On Friday, The Wall Street Journal left a giant blank space on its front page with an image at the top of the page of Mr Gershkovich in the newspaper’s signature pencil drawing and a headline that read: “His Story Should Be Here”.

Mr Gershkovich’s family wrote a letter in the same edition, saying that “it has felt like holding our breath”.

Russia ranks within the bottom 20 countries in the world for press freedom, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), which releases a report every year. The global press freedoms watchdog said that since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, almost all independent media have been banned, or blocked, and all others are subject to military censorship.

It is tantamount to state hostage-taking

Rebecca Vincent, director of campaigns at RSF

Several Western media outlets, such as the BBC, are no longer accessible in the country – and many Russian and foreign correspondents have been forced to flee.

RSF said that this month alone, six journalists in Russia have been detained, including a reporter who covered the trials of Alexei Navalny before the Russian opposition politician died in suspicious circumstances in an Arctic penal colony in February.

Rebecca Vincent, director of campaigns at RSF, said Mr Gershkovich’s arrest and continued detention was “tantamount to state hostage-taking”.

“[His] unjust detention for a full year now in Russia is a stark reminder of the dire press freedom situation in the country, which has deteriorated sharply since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine,” she told The Independent.

Gulnoza Said, the Europe and Central Asia programme coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists, told The Independent it is clear that Russia is “determined to keep him behind bars for as long as possible”.

“After February 2022, thousands of journalists fled. There is an unprecedentedly high number of journalists in Russian prisons. Until Evan’s detention, foreign correspondents were at risk but they thought they might be expelled or banned from entering Russia. With Evan’s case, a red line was crossed.”