Jupiter may have been flat at one point, not spherical

Large planets like Jupiter that form far away from their host stars may start forming as flattened disks similar to a fluffy pancake rather than as spherical structures, according to a new study.

Astronomers have discovered thousands of planets outside the Solar System so far, however, it remains unexplained how these worlds form.

In the new study, scientists used computer simulations to model the formation of planets based on the theory that young planets, or protoplanets, form in short timescales from the breaking up of large rotating disks of gas orbiting young stars.

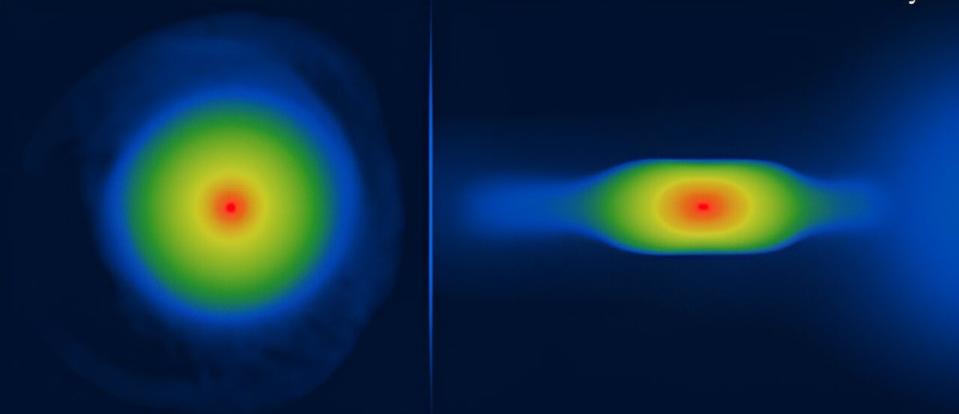

The research found that protoplanets are more likely to have flattened structures called oblate spheroids – similar to the shape of a Smarties or an M&M candy.

“We have been studying planet formation for a long time but never before had we thought to check the shape of the planets as they form in the simulations. We had always assumed that they were spherical,” study co-author Dimitris Stamatellos said.

“We were very surprised that they turned out to be oblate spheroids, pretty similar to smarties,” Dr Stamatellos said.

In the research, astronomers determined planet properties, compared them with known observations, and examined the formation mechanism of gas giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn.

They assessed the shapes of young planets and how these may grow to become large gas giants.

The study also probed the properties of planets forming in different conditions like varying temperature and gas density.

Until now, researchers have theorised that planets form via one of two processes.

One of these is a process called “core accretion,” which is the gradual growth of dust particles that stick together to form progressively larger and larger objects on long timescales.

Planets may also form directly by the breaking up of large rotating disks of material around young stars in short timescales by a process called the theory of disk-instability.

The second theory has been appealing since it explains how large planets can form very quickly at large distances from their host star.

Scientists hope future observations of large planets in formation can confirm how these worlds actually form.

Researchers also found in the current study that new planets grow predominately from their poles rather than their equators as material falls onto them.

“The large majority of the protoplanets that form in the simulations are oblate spheroids rather than spherical, and they accrete faster from their poles,” scientists wrote.

This finding could also help inform astronomers which viewing angle they must take with their telescopes when observing planets under formation.