Kansas City’s Negro Leagues Baseball Museum hits the road for traveling exhibit. Take a look

Brandon Lunsford gushed about the large crates he received from the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum — and he wasn’t expecting so many.

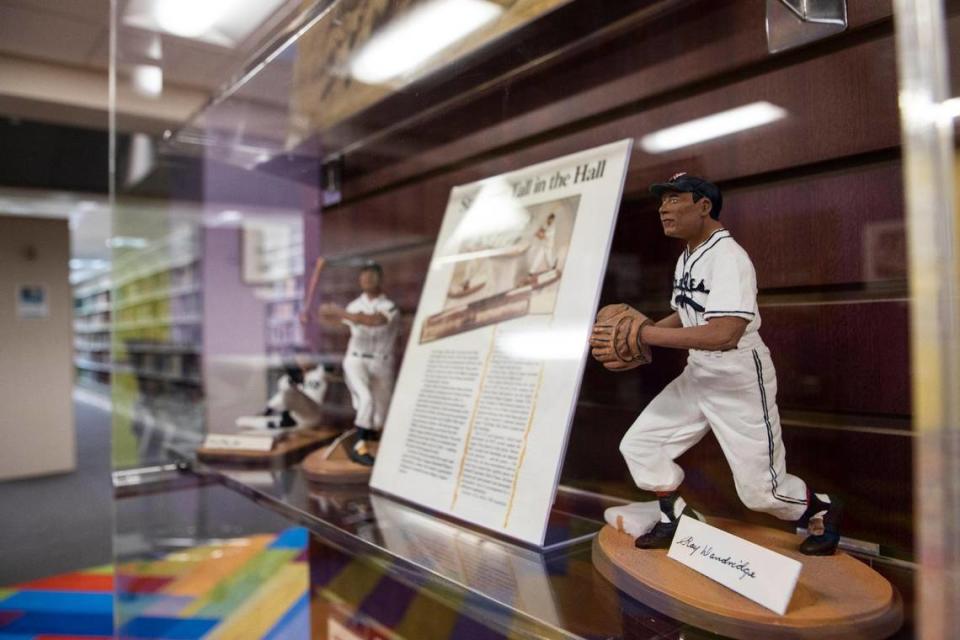

Inside was a trove of memorabilia from the Kansas City, Missouri-based nonprofit that preserves the legacy of historic Black baseball teams, including some that were based in North Carolina. Lunsford, the archivist at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, said with so much to dig through and limited space, he had to be selective with the display he was building.

The traveling exhibit, now adorning the walls at the school’s James B. Duke Memorial Library, is available for public viewing through June 7. The exhibit also showcases rare photos of JCSU and Second Ward High School baseball teams. Second Ward was Charlotte’s first all Black high school, opening in 1923.

‘Is that a hornet’s nest on your cap?’ Paying homage to Charlotte’s Negro League team

“I think it’s important to the community because it’s kind of a piece of history, I think (that) is kind of lost, especially in Black communities,” Lunsford told the Charlotte Observer this week. “I’ve seen a lot of people being very surprised about it.”

Last year, Lunsford had a fruitful conversation with Erin DiCesare, a JCSU professor of Interdisciplinary Studies. She was writing an article about the social significance of the Negro Leagues. That conversation ultimately led to the museum trip. A chat with its curator followed, and grant funding did the rest.

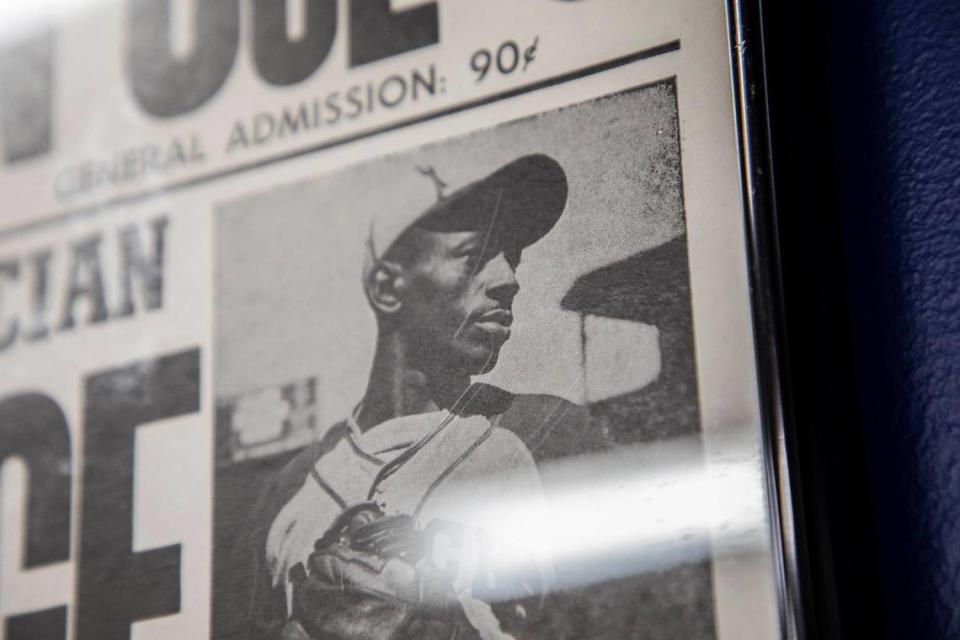

The exhibit traces the origins of professional Black baseball in the 1860s, chronicling the stories of Black players on Black-owned and managed teams. It also features photos of iconic athletes in their prime: Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Ernie Banks and Jackie Robinson, to name a few.

Lunsford hopes the public will discover little-known facts about Negro Leagues baseball when they see the exhibit. Some nuggets:

Integration before Jackie Robinson?

Students saw the exhibit and told Lunsford they never knew Black players integrated the game before Jackie Robinson.

History touts Robinson as the first African American baseball player to sign a contract with Major League Baseball in 1947, during the modern era. But in the mid-to-late 19th century, professional leagues featured integrated teams, Lunsford said.

In that period, the National Association of Professional Baseball Players and the American Association of Professional Baseball Players were kings; there was even an international association, he said.

In 1872, Bud Fowler became the first paid Black player on the roster with an all-white team in White Castle, Pennsylvania. In 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker became the first Black player on a team in Toledo, Ohio, in the American Association.

“Almost 100 years before (Robinson) ever integrated the game, there was Black baseball,” Lunsford said.

Opportunities for Black baseball players were more plentiful up north, he said.

White teams often would integrate with Black players who were lighter-skinned, who perhaps passed as American Indian or Latino because that was considered more acceptable, he said.

Charlotte’s rich Black baseball history

The Queen City’s first all-Black baseball team was the Charlotte QuickSteps, which began playing in 1890, Lunsford said.

Others, such as The Biddle Stars, represented smaller Charlotte communities. That roster mostly was comprised of players from the former Biddle University (now JCSU) and neighbors from Biddleville, as reported by Michael Webb on CLTure.org.

Other teams included the Charlotte Black Hornets, in existence from 1910, the Charlotte Red Socks and the Charlotte Sluggers.

Several Black teams played each other. They also would play white teams and mill teams. JCSU and Livingstone College would match-up on Easter Monday in a classic pairing.

“It was like a social status to hear these games. And these players were heroes in their communities. And it was a place for people to be seen (and) see people,” Lunsford said.

Black baseball was played in Charlotte well into the mid-to-late 20th century, he said. There were integrated teams by then, but teams still played in smaller neighborhoods.

Lunsford notes it was hard to keep these teams’ records and statistics because many white newspapers were selective in what they covered, he said. The Observer’s archives include stories about the Black Charlotte Hornets and other local teams. Many records may be kept in the Charlotte Post, a Black-owned publication, Lunsford said.

When Jackie Robinson signed in the major leagues, more people started going to see him and more players followed his lead. Black-owned teams began to lose traction and eventually shut down.

“It was a completely Black-owned and -operated business. It never should have been segregated, obviously,” he said. “But when it happened, it destroyed something that was kind of unique.”

Night games

The tradition of night games evolved from the Negro Leagues. Baseball was a sport, but it also was entertainment for the community. Folks who attended games expected to see a show from an all-Black team. In 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs was among the first to host a night game, Lunsford said.

The Negro Leagues teams would bring out these giant lights, just to have fun and play around, he said.

“They also had a real flashy way of playing and they would do all these tricks with each other,” he said. “It was really popular.”

Want to go?

What: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s traveling exhibit on loan from Kansas City, Missouri.

Where: Johnson C. Smith University, 100 Beatties Ford Rd.

Dates: Through June 7.