Kentucky’s role in slaves’ emancipation: ‘Camp Nelson is our Canada’

In our Uniquely Kentucky stories, Herald-Leader journalists bring you the quirky and cool, historic and infamous, beloved and unforgettable, and everything-in-between stories of what makes our commonwealth remarkable. Read more. Story idea? hlcityregion@herald-leader.com.

Isaac Hawes was born into slavery in Clark County in 1830.

In 1864, as a still-enslaved man, he made the dangerous and difficult journey to Camp Nelson in Jessamine County where Black men could enlist in the U.S. Army. He became part of the 122nd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops, earning his freedom even though slavery was still legal in Kentucky.

Hawes was eventually stationed in Galveston, Texas, and he was there on June 19, 1865, when Gen. Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, enforcing President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation that abolished slavery in the Confederate states.

That day became what’s now the federal holiday of Juneteenth.

Hawes survived the war, and ended up dying in 1916 at a veterans’ hospital in Ohio. He is buried at African Cemetery #2 in Lexington along with 153 other soldiers from the U.S. Colored Troops.

(In one of those strange twists of history, Granger ended up buried just a few miles away at the Lexington Cemetery.)

“It’s such an amazing story — they see the moment of Juneteenth in Texas, and then they come back to Kentucky and no one is free yet,” said Yvonne Giles, a local historian who restored the cemetery. She researched the many stories of men like Hawes who enlisted and trained at Camp Nelson and then were buried at a segregated cemetery in North Lexington.

As Juneteenth gets underway with celebrations of the end of slavery, the story of Hawes and his fellow soldiers from Camp Nelson reminds us just how complex emancipation really was, particularly here in Kentucky.

“I think Kentuckians should know that this state played a pretty central role in pushing emancipation along in this country,” said Amy Murrell Taylor, a University of Kentucky history professor and the author of “Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps.”

“Emancipation came because of determined actions of enslaved people themselves,” she said. “It was not given to them, and that’s what Camp Nelson represents.”

‘Camp Nelson is our Canada’

Kentucky’s slow and winding route to emancipation is getting more attention, thanks to Camp Nelson’s rolling hills and palisades becoming a national monument site in 2018 after years of stewardship by Jessamine County officials.

The move to create the commonwealth’s first national monument site, pushed by Kentucky’s U.S. Rep. Andy Barr and Sen. Mitch McConnell, meant that federal resources could be used to further explore the history there.

“Ensuring its recognition as a National Monument helps preserve this vital piece of history, reminding us of the sacrifices made and the progress achieved,” Barr said in a statement. “It is an honor to support and advocate for Camp Nelson and to bring its story to the national stage.”

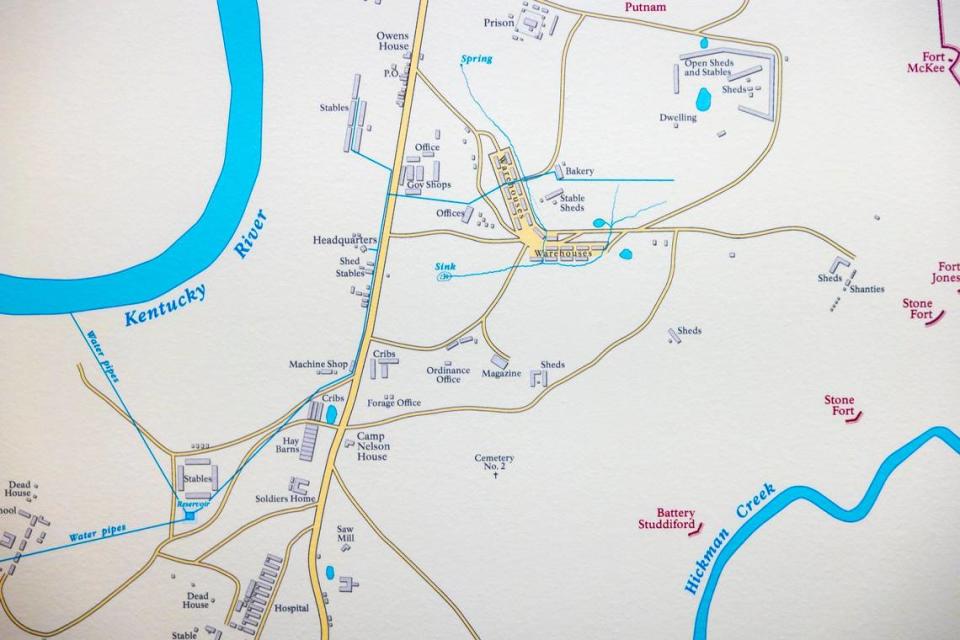

Camp Nelson sat at a crucial junction near one of the few bridges over the Kentucky River. Enslaved people built a series of battlements around the property starting in 1863. By the next year, as racial restrictions on enlistment were lifted, they were instead coming to be trained as soldiers who were now free.

Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. But it only affected states in open rebellion against the United States.

In one of those impossible ironies of history, Kentucky had not joined the Confederacy, so it could still keep people in slavery and enthusiastically did so. As word spread that freedom waited at a Jessamine County military camp, more and more enslaved men, women and children made their way there, risking punishment, jail or death.

“It’s an amazing time,” said Steve Phan, Chief of Interpretation for Camp Nelson.

“People traveled in every direction they could to escape slavery, and many of them came here. ‘Camp Nelson is our Canada,’” they said.

By the end of the war in 1865, more than 23,000 African Americans had joined the U.S. Army in Kentucky. That made it the second-largest contributor of United States Colored Troops from any state. More than 10,000 were either enlisted or trained at Camp Nelson.

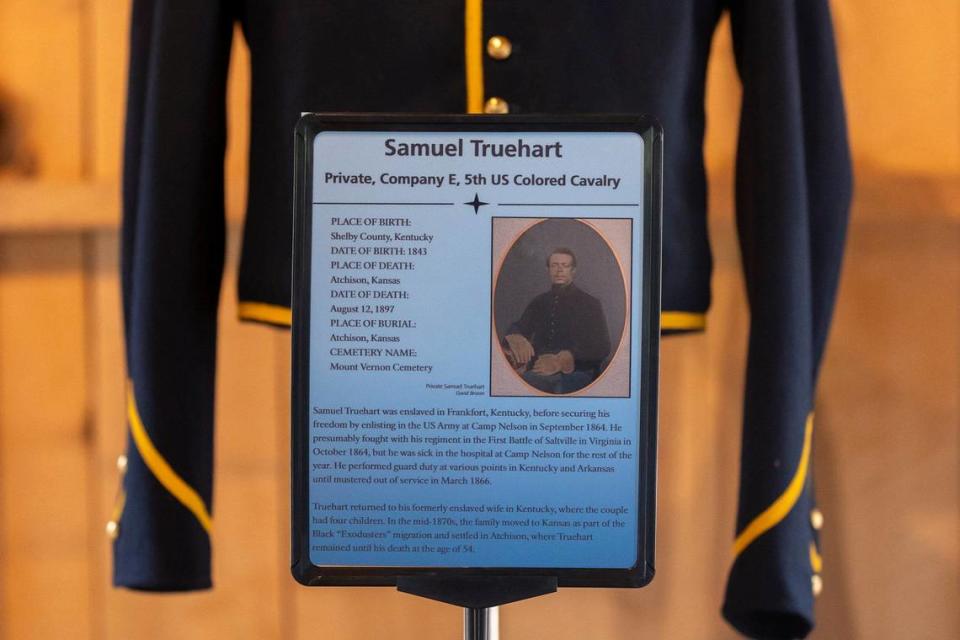

Phan is helping design and expand the installations that explore the stories of men like Samuel Truehart, an enslaved man from Frankfort who made his way to Camp Nelson in 1864, fought in Virginia and then was part of the Exodusters, former Colored Troop soldiers who helped settle Kansas.

Or Elijiah Marrs, an enslaved man in Shelby County, who organized 27 other men armed with clubs and walked to Louisville to enlist. He was trained at Camp Nelson, and after the war, he co-founded Simmons College in Louisville. Much of the information they’ve used has come directly from the descendants of those first freed soldiers, Phan said.

But Phan noted it’s important for people to understand that for every movement forward, there was backlash.

Truehart, for example, was a member of the 5th U.S. Colored Troops who fought at the Battle of Saltville in Virginia. The U.S. Army retreated, leaving many troops behind, including members of the 5th USCC, about 40 or 50 of whom were slaughtered by Confederate troops after the battle. It’s now known as the Saltville Massacre.

Many men who made their way to Camp Nelson were accompanied by women and children. The Army had not made provision in either space or resources for all the people, so it would habitually expel them.

During a bitter cold spell in November 1864, the Army sent away more than 400 Black people, most of them women and children. More than 200 people died of exposure and illness. First-person accounts of the tragedy made their way to Washington, and by March 1865, Congress had passed a law that freed wives and children of any Colored Troop soldiers.

The Army also constructed the Camp Nelson Home for Colored Refugees across the road from the camp, which was briefly led by Rev. John Fee, the founder of Berea College.

“There is so much triumph and tragedy here,” Phan said. “But it’s important to remember that African-American men use the military service as an opportunity to secure their civil rights. They’re fighting for the rights of citizenship.”

A national holiday

Not even military service was enough to secure those rights fully. Black men still faced terrible danger and injustice after the war as Reconstruction gave way to Jim Crow laws.

“For reasons I still don’t fully understand, white slave owners in Kentucky still believed they could keep slavery going even as it’s collapsing everyone else,” said UK’s Taylor.

“They’re still buying and selling, which is a reflection of some confidence in the future. Then they are going to great lengths to pass new state laws to protect slavery — that determination of white Kentuckians to hold on does create a really volatile and dangerous environment for becoming free.”

But Kentucky was forced to face the reality of the 13th Amendment when it was ratified by 27 of the 36 states in December 1865. (Kentucky did not ratify it until 1976.)

For many years, Black communities celebrated the different days they became free, or learned they were free. But Texas’ celebration of Juneteenth became the best known, and it became a national holiday in 2021, the first new federal holiday since Martin Luther King Jr. Day was adopted in 1983.

There’s no better place for Kentuckians to celebrate Juneteenth than Camp Nelson because no other place hosted and accelerated emancipation to such a degree. The National Park Service has big plans to expand the monument site — restoring the white house off the highway that housed Camp Nelson’s officers and working to explore what’s left of the refugee home across the road.

“Thousands of soldiers and women and children were emancipated there,” said Steve McBride, a historian who helped oversee the transition of Camp Nelson to the park service.

“It really began the destruction of slavery in Kentucky. It happened there.”