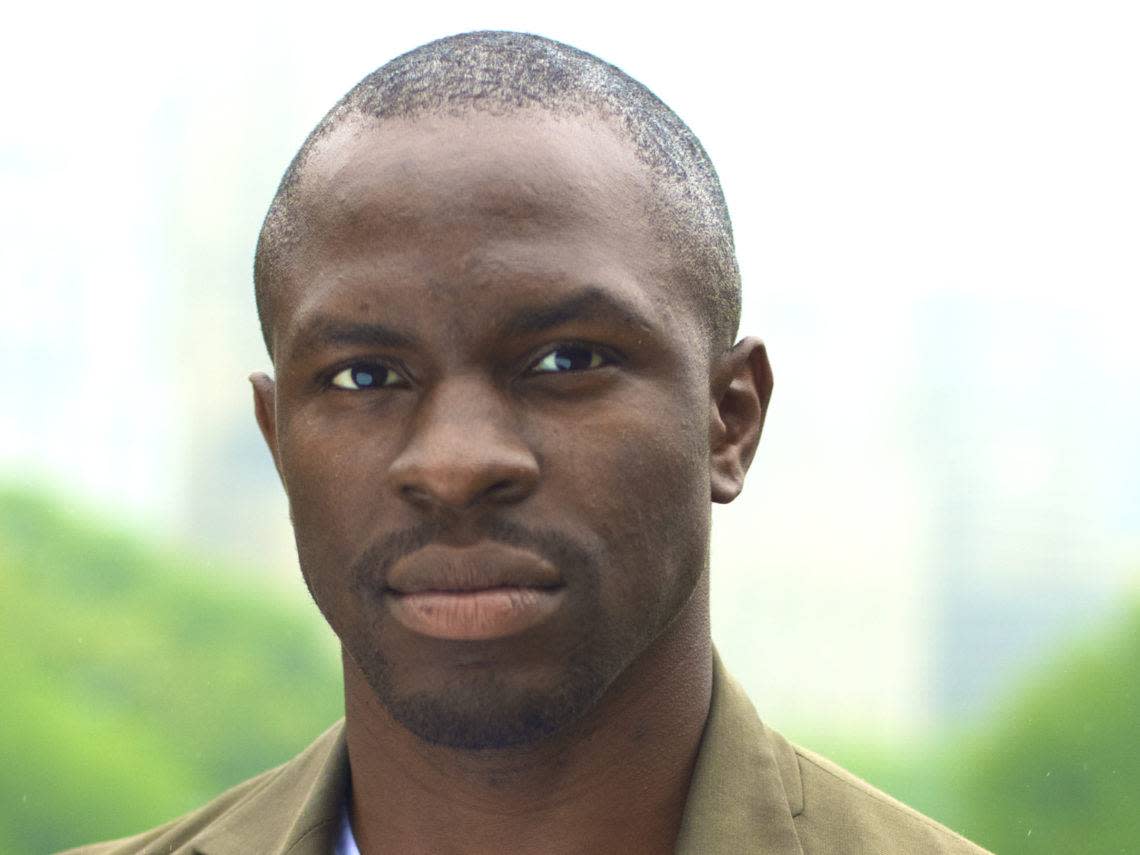

‘To Kill A Mockingbird’s Gbenga Akinnagbe Is Taking New York, From Broadway To Tribeca And An Intersection In Flatbush

Every show night at Broadway’s Shubert Theatre, Gbenga Akinnagbe resurrects Tom Robinson, bringing to life that most anguished of all the mockingbirds in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. But “anguished” doesn’t fully encompass this version of the doomed, falsely accused black field hand on trial for raping the white Mayella Ewell. The Tom Robinson of Aaron Sorkin’s adaptation, so persuasively drawn by Akinnagbe, is, like this production as a whole, an uncanny mix of old and new, yesterday and today.

A few miles to the south, at the Tribeca Film Festival, Akinnagbe (full name pronounced BENG-gə ə-KEEN-ə-bay) is appearing in two films: He plays ex-convict Marcus in Henry Hayes’ short film Rogers and Tilden (named after a street intersection in Flatbush), and the title character’s father in Sam de Jong’s feature Goldie. As a director, Akinnagbe is repped in the festival by the pilot episode of DC Noir, running in the festival’s TV section. He’s also a juror for the International Narrative Feature Competition.

Related stories

'Sing Street' Musical From 'Once' Team Set For Off Broadway World Premiere

Deadine spoke to Akinnagbe (known to TV audiences for The Wire, The Good Wife and his stand-out performance as Larry, the emotionally, well, complicated pimp in HBO’s The Deuce) about this most recent burst of New York visibility, his new characters, what drew him to them, and what they say of our times.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Deadline: Let’s start with Rogers and Tilden. Tell me about your character.

Gbenga Akinnagbe: I am the lead character, who’s been away in prison for a number of years and everything’s changed, I’ve been away long enough to be uncomfortable with the current technology like cell phones so get an opportunity to be back in society, getting a job, getting a stable place, a lot of it depends on having an ID, a driver’s license, and if some important papers like your birth certificate and other things have been moved around and destroyed because you haven’t had a stable house or you’ve been away for a long time, or your family is dispersed or dead, this actually happens quite a lot. So, my character has come back and for him to get the job that he needs to stay out of trouble, he needs an ID and so, this film is all about him getting this small but crucial bit of ID to start his life again.

How did you get involved in this project?

Akinnagbe: The really cool casting director reached out to me and my reps, her name’s Kate and I think she’s cool because she has a really good eye as far as cool projects. I spoke to the director and the co-writer. The two writers wanted to tell this small but important story and the way they wanted to do it was, I thought, honoring the characters involved, the neighborhood involved, it wasn’t exploitive and it was well written. I was like, all right, let’s do this. Let’s tell this story.

And Goldie?

Akinnagbe: I had a great time doing that with a young lady named Slick [Woods], she plays the lead role of Goldie and actually, now that I think about it, this is also somebody who’s literally trying to get a stable home for her and her sister and keep her family together. Her family’s falling apart and separated and her sister put into the system so Goldie is trying to keep things together as best as she can, with the limitations that she has.

I play Goldie’s father. When Goldie was younger, she and her father were really close and then when the parents split they, which oftentimes unfortunately happens, the child is used as a pawn and so distance grows between the father and the daughter. He hasn’t seen her or talked to her in a long time and she’s angry, rightfully so, and resentful and now that he’s remarried and has a new kid and going to start again, Goldie has come back because she has nowhere else to go. He wants to help, wants to take her back but you know, the new family dynamics make it very difficult, so she has to continue this kind of journey to save her and her sister’s life, but the best way she can.

And as I describe that it reminds me of The Sun Is Also A Star, which is a film I’m in coming out in May, and it deals with immigrants [facing deportation] and it’s funny, as I’m talking to you, I’m starting to see the connections…

Perfect, because that’s just where I was heading. Everyone knows, or thinks they know, Tom Robinson, the character you play in To Kill A Mockingbird, so can you draw comparisons to these other characters you are playing now? Or how are they different?

Akinnagbe: I think what [Marcus] and Tom have in common is that they are men who’ve been subject to the system for their entire lives, the power of the state has dictated a lot of the opportunities that they had or didn’t have. With Tom, who’s an innocent, the tragedy is compounded even more so because he ends up losing his life to the injustice of the system, the racism of the system and a lie. With Rogers and Tilden, [Marcus] committed a crime years ago and paid his debt to society and is now out.

So in these two stories, there’s one in which someone is a complete innocent and has been railroaded and another where someone has committed a crime, though obviously you have to take how and why into consideration but anyway he’s paid his debt, so do we continue to punish him? Do we continue to disenfranchise him? Once they’ve done what society says this is what you need to do to make it right, do we make them whole again when they come back?

The timing for this film is uncanny. Bernie Sanders is getting roasted right now for asking that. Of course he stepped in hot water with the Boston bomber question…

Akinnagbe: Yeah. He’s talking about people that a lot of people consider haven’t paid their debts, and they’re in prison paying their debts. I do get his point, like there are some things that we as a society should not be able to take away because there are birthrights in a democracy, and once you start taking them away that’s actually how you start to disenfranchise, and you dismantle your democracy without knowing that you’re doing it. So I get his point, but I also see the other side of the argument that, yes, once you’ve paid your debt you should be fully reinstated as a citizen but people who have not paid their debts still owe society, so they should not be reinstated fully as full citizens with all the rights and privileges. I think it’s really good that we’re having this discussion right now because we’re in the midst of redefining a failing democracy, or at least identifying it in a most honest way, our failing democracy. This discussion is pertinent.

You and I spoke briefly before Mockingbird opened and, without putting your own words in your mouth, you spoke about what you wanted for this Tom…

Akinnagbe: Yes, an acknowledgement that Tom has some agency in his own life that maybe he didn’t have, let’s say, in the film or the novel. That was attractive to me as an actor, as an artist and I think it tells a more interesting and more complicated story. Obviously that starts with good writing and how it was conceived with the creative team, and the actors and the year of workshops that we did. It was the same with LaTanya’s character, Calpurnia [LaTanya Richardson Jackson plays the Finch family housekeeper]. She’s the only adult in the play who’s not only on Atticus’s side but who contradicts him, who forces him to see a more complicated view of the world. She speaks oftentimes for the audience, for what people are thinking, and that was enabled by giving her character, her black character, like Tom’s black character, more agency in the world we’ve created.

What was your relationship To Kill a Mockingbird before you got involved with the stage production? I’m always surprised that there are people who haven’t seen the movie or read the book. What was your history with it?

Akinnagbe: I’ve read excerpts of the book once or twice in school, but I never read the entire book. I knew that it was this big important thing that was kind of a right of passage, and I was in and out of special ed all through adolescence and elementary so I had a kind of different path than a lot of people. There were a lot of books that I didn’t read or things that people normally do in public school that I didn’t do. So it was this kind of thing I was aware of, and knew that it was a movie. I’ve seen the movie, or excerpts of it when I was younger. So funny enough, getting to the workshop of this play with Aaron and Bart, I came to it with not with as much nostalgia and ownership that most people have of it, about how it touched them and affected them in particular at special times in their lives growing up. I didn’t have that. This was a whole new piece to me, a whole new project, something that we’d get to create and dissect. We dug a lot into the historical aspects of the time, the place, the politics, race, read books about Harper Lee’s father and his role in that town. So we had to dissect it in a ways outside of just the book.

In a way, you were lucky, no baggage. I would imagine Aaron and everyone involved wanted the audience to see this Mockingbird as something entirely new, not a movie on stage.

Akinnagbe: Exactly. There was this weight, especially in the beginning when people would show up basically daring us to screw up their favorite novel. There was this weight in the audience that you could feel, and then the play like just opened and said, all right, come on, this is the Atticus of the novel you love but we’re doing something different and come with us. And people have come with us.

When I was sitting in the audience it felt to me that after about 10 minutes or so there was a sort of collective breath, like, we’re going to be okay here, they’re not destroying anything. I think it’s when the audience first laughs with the kids – Scout, Jem and Dill – who are played by adult actors. That’s when everyone gives themselves permission to go with it.

Akinnagbe: You’re right on, and we’ve spoken about that as a cast. It’s when you laugh with the kids. Because people do come in apprehensive, one, because it’s their favorite novel or movie, and two, because adults are playing kids. When audiences get permission to laugh, especially in a play about a subject that’s so serious, they’re instantly into it and they’ll go with you.

And how long will that be, by the way? How long will you be with the show?

Akinnagbe: A long time. I’m loving it and I’ll be there as of now until November. So, it will have been a year.

That’s a good long run. And then?

Akinnagbe: Good question. I have some projects that are in the ether, but nothing confirmed yet. As an actor things get more concrete, like, a couple months out if you’re lucky. Sometimes a couple weeks out. But there’s some things I’m looking to do, awesome projects in a producorial vein if they line up right, time-wise, that maybe I’ll be able to start doing when Mockingbird ends. There are a couple of films [already shot and set for release] and I can feel that part of me itching again.

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.