The latest on Riverfront Stadium? Developers want TIF money to build by it

Update, Oct. 17: The Wichita City Council on Tuesday approved holding a public hearing on changes to the West Bank Redevelopment District on Nov. 21.

Original story: When Wichita announced plans to demolish Lawrence-Dumont Stadium and build a new Triple-A ballpark, city leaders promoted the $80-million-plus public investment as a catalyst for private development surrounding the stadium.

The city sold land to developers for $1 an acre, moved McLean Boulevard, agreed to a subsidy package and tapped the state’s COVID-19 emergency funds to help boost private development on the west bank of the Arkansas River.

It wasn’t enough, city officials say.

Now, to spur private development, the city is poised to give to developers a key revenue stream that originally was supposed to help pay down stadium debt. If the City Council doesn’t approve the change, the city could lose the project — along with more than $39 million in projected city revenues from hotel taxes, guest taxes, added sales taxes and diverted state sales taxes over the next 20 years.

City officials say EPC Real Estate Group won’t build a hotel, apartment complex, parking garage or 10,000-square-foot retail space without creating a special carve-out in its tax increment finance, or TIF, district for private development. TIF money from the west bank development was dedicated to help pay for the stadium under the original proposals in 2017 and 2019.

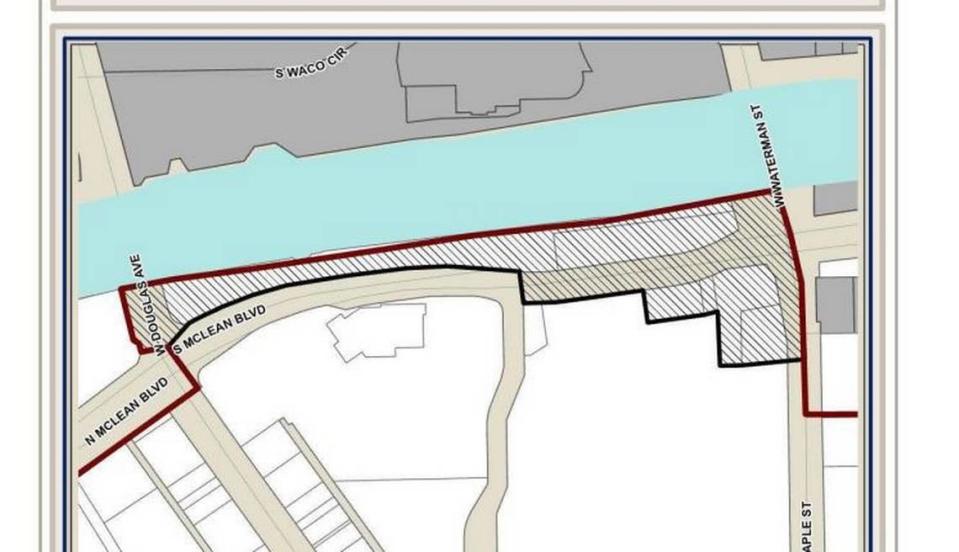

The EPC development area is in a TIF district that was set up to pay for Riverfront Stadium and improvements in and around Delano. Segregating it within the district would ensure any property taxes created by EPC’s project — up to $11.3 million — would not be used to pay for the baseball stadium project. Any amount above that could be used by the city for riverfront improvements and other eligible expenses.

The first $11.3 million in TIF funds generated in the carve-out would go toward financing and infrastructure costs supporting EPC’s hotel, apartment complex, retail space and parking garage.

Representatives for EPC were not immediately available for comment and did not return a phone call Monday.

Not everyone agrees with the plan.

Council member Jeff Blubaugh, who represents the district that includes the ballpark and was the only council member to vote against a new development deal for the west bank in August, questioned city staff on Friday about whether the city has ever done something like this.

“I’ll be looking at what percentage (of the development project that) will be going to debt service for the stadium,” Blubaugh said.

Mayor Brandon Whipple, who voted for a new development agreement with EPC in August that committed the $11.3 million in TIF funds to the developers, is joining Blubaugh in questioning the project.

“At what point are we just throwing good money after bad?” Whipple said in an interview Friday. “I think if we start supplementing the profits, I think that’s where we start seeing that.”

Whipple said the City Council could pause a vote scheduled for Tuesday that would set a public hearing in November carving out a special project area within the tax increment finance district for EPC Real Estate Group, a development company that bought riverfront property from the city in August for $1 an acre after the former Wind Surge ownership team failed do anything with the land.

“The only plan I’m going to be supportive of is the one that helps us pay down the debt for the baseball stadium,” Whipple said.

The move would essentially shift $11.3 million to EPC that could have gone toward stadium infrastructure costs, as was envisioned when the TIF district was created in 2017 and 2019.

Assistant City Manager Troy Anderson said the City Council already approved awarding $11.3 million in pay-as-you-go reimbursements to EPC when it approved a development agreement with the company on Aug. 15. But there was no mention by city staff to the city council that EPC’s development would be segregated within the existing TIF district.

EPC won’t move forward with the project unless the city approves the $11.3 million subsidy, Anderson said. The change is needed because EPC won’t be able to see a large enough return on its investment to get underwriting for the development without the additional incentives, Anderson said.

With the additional incentives, EPC would see a return on investment of 8.5%, or $9.35 million, according to an analysis of data in the city’s agenda report. Anderson said the city would still receive $39 million in other revenue from the completed project over the next two decades, some of which could be used to help pay for the stadium’s $83 million debt.

Without the development, the city won’t capture any revenue in the area to help pay for the stadium, Anderson said. And $39 million is a lot better than nothing, he said.

“Our debt service obligation already exists,” Anderson said. “This (development) helps us pay that debt service. But if we don’t get this revenue, we’ve got to figure out some other way to pay for that debt service.”

Anderson acknowledged the city would make less revenue from the development if it carves out the EPC district from the stadium district, pointing to a table showing a decrease in revenue for the city and an increase in benefits to developers that was included in the Aug. 15 agenda report. He still thinks it’s the best deal the city can hope for at this point, as the city prepares to begin making debt payments on the ballpark.

“There’s a little bit of a sense of urgency,” Anderson said. “And this is a good deal, right? We get multifamily residential (apartments). Our community — our downtown needs it right now, wildly. We’ve got a brand new biomedical center that’s coming, and we’re gonna need multifamily residential. Hotel — our downtown is continuing to thrive and grow. We’re gonna need more hotels. So this is a good deal.”

It’s the latest test for a baseball stadium project that has not gone as planned. Whipple said the city should be cautious because it has a track record of revealing additional details of development deals to the public only after the City Council has approved the overall plan.

In 2019 and 2020, Wichita built one of the most expensive ballparks in Minor League Baseball to lure the New Orleans Baby Cakes — now the Wichita Wind Surge — franchise away from Louisiana. After the city tore down Lawrence-Dumont Stadium and approved multiple deals with the Wind Surge, the city disclosed that the deal hinged on a sale of 4 acres of riverfront property to the team owners for $4.

In March 2019, to combat criticism of the deal, the city and Wind Surge management unveiled flashy plans for the west bank of the Arkansas River. The plans included restaurants and bars along a riverfront boardwalk, a pedestrian footbridge connecting the stadium to downtown, an outdoor ice-skating rink and a massive Ferris wheel illuminating the entire area in a whimsical glow of pink and orange lights.

None of it has been built.

The stadium was originally envisioned as an economic engine that would draw thousands of people multiple times a week to the stadium district. The visitors would spend money at the surrounding businesses, growing the city’s tax base and helping to pay back the cost of the stadium, backers said. It would eventually pay for itself.

Instead, over the past four years, public investments and subsidies have increased while the projected money coming back to the city has dropped by millions of dollars. Elected officials are starting to question whether the development plan is working, as developers seek additional subsidies before they’ll agree to build supporting development that would eventually ease the city’s cost-burden for the stadium.

The team’s start in Wichita was filled with setbacks. Its inaugural season in Wichita was canceled because of the pandemic, the team’s owner died of COVID and Minor League Baseball downgraded Wichita’s team from Triple-A, one step below the majors, to Double-A before it ever played a game in the new stadium.

The Wind Surge’s first two seasons saw higher-than-expected prices, illegal hidden fees and low attendance. This year, after a change of ownership that lowered prices on attendance and concessions, the Wind Surge had one of the biggest attendance turnarounds in Minor League Baseball, increasing attendance by more than 40% compared to 2022, according to an analysis by Baseball America.

City leaders in August remained optimistic that a new development team could save the stagnant plans on the west bank.

But Whipple said the latest ask by developers and city staff makes him wonder.

“This is prime real estate,” Whipple said. “If a developer can’t make money from a hotel and an apartment complex overlooking downtown and a brand new stadium, maybe there’s something else going on here. That’s why I think it’s important to take our time on this and make sure the public and the electeds have all of the details and information we need to understand why this is necessary.”