‘We’re from here.’ LGBTQ Eastern Kentuckians creating community that’s been missing

The small moments are the ones that let Cara Ellis know she’s making a big impact.

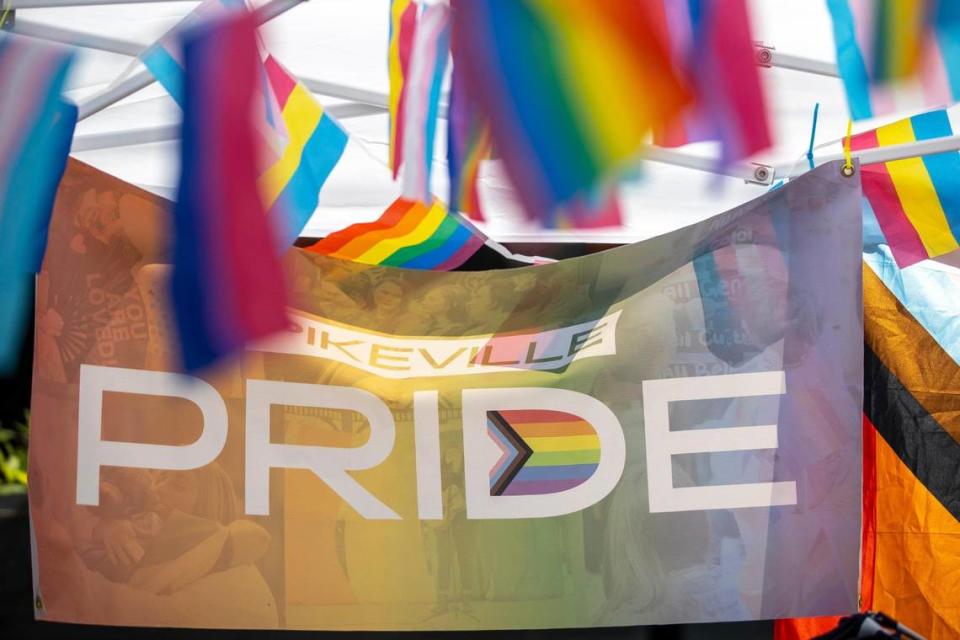

On a hot, mid-April day at Hillbilly Days — Pikeville’s annual festival celebrating all things Appalachia — Ellis and other members of Pikeville Pride sat at a booth strewn with rainbow flags and banners. The grassroots organization works to highlight Eastern Kentucky’s LGBTQ+ community.

In a town and region long assumed to be unwelcome to LGBTQ+ people, members were met with honest questions, smiles, thank yous and even a “grandma” who got their grandson their “first pride flag,” said Ellis, who is Pikeville Pride’s president.

“I never thought we would have this in this town,” said Ellis, a Pikeville native.

Ellis has come out twice in her life. Once in high school, where she was met with bullying that made her much more quiet about an essential part of herself.

But a cancer diagnosis in 2019 changed that. She came out on Facebook with a statement that essentially said “I’m here and I’m queer and that’s all you need to know,” Ellis said.

The reception was much warmer which, according to Ellis, is becoming more of the norm in Eastern Kentucky — a place where many might have assumed that those within the LGBTQ+ community are already gone or going soon.

Online hate mail can occasionally be expected but in-person intimidation is a rarity, multiple queer Eastern Kentuckians told the Herald-Leader. Thanks to Pikeville Pride, one of the region’s biggest cities has had Pride celebrations since 2018.

Still, it’s never been necessarily easy to be gay in the mountains, and a ratcheting up of anti-LGBTQ rhetoric and legislation, both in Kentucky and nationally, will make life harder for those who are out in rural communities, many said. The state legislature’s passage of Senate Bill 150, banning gender-affirming healthcare for transgender youth, will make life especially hard for those kids.

“It is just an attack on the entire community but particularly I feel like trans youth are getting hit the hardest with these bills,” Ellis said.

In the classroom

Willie Carver Jr. knows all too well the struggles LGBTQ youth face in rural areas. While teaching high school in Montgomery County, Carver was named the state’s teacher of the year in 2022. But not long after, Carver, who is gay, left the K-12 classroom after facing discrimination.

The suicide rate among LGBTQ youth is much higher than their peers. A national survey conducted last year by the Trevor Project, an organization that provides crisis help for LGBTQ youth, found that 45% of LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year.

Kentucky’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population is estimated to be 144,000 people, said a 2020 study from the University of California-Los Angeles’ Williams Institute, a research center focused on gender identity and sexual orientation.

During his 17 years in the classroom, Carver said he’d received several suicide notes from students. The school used an app called Remind that allowed students to message teachers.

“I got multiple messages from students who I guess were saying goodbye and luckily (I) was able to intervene and save them each time,” Carver said.

But that suicide rate goes down if students come from households that affirm their gender identity, attend an LGBTQ-affirming school or live in an accepting community, the Trevor Project survey said. A separate Trevor Project survey from 2021 found that among rural LGBTQ youth, nearly half said their communities were at least somewhat unaccepting of LGBTQ people. Meanwhile, just 26% of youth living in urban areas felt the same way.

As Carver puts it, having at least one affirming adult in a student’s life cuts the suicide rate in half.

“For I would say half of my LGBTQ students, I was the single affirming adult,” Carver said.

SB 150 — which bans lessons on gender identity and sexual orientation and stops school districts from requiring teachers use of a student’s preferred pronouns — “will illegalize that affirming adult, because you can’t reference it or talk about it,” Carver said.

But not everyone can get that affirmation in the classroom. Twenty-five-year-old Jace Fraley said his main support at the private, Christian high school he attended was his best friend. Fraley wasn’t out then but felt “very out of place.”

The school’s dress code felt constraining, said Fraley, a transgender man from Floyd County who transitioned as a young adult.

“They would try to make the girls wear dresses but I would just wear sweaters and dress pants,” Fraley said.

At home

Fraley came out in 2016 in an online post and lost some family, friends and “people that I don’t even know” over it, he said. But some of his family kept an open mind and have been supportive.

“There are a few that still call me my old name and try to say that I’m a girl even though I have a full beard,” Fraley said.

Some youth don’t get any affirmation at home. Crockett Ward, the director of education and outreach at Pikeville’s Appalachian Center for the Arts, does much of the theater education at the center.

He’s handed out scenes and short plays for students to prepare and perform. But some students have requested not to do scenes that have to do with LGBTQ+ content.

“Some of my students have come to me and been like, ‘look, I can’t do this piece, my parent, my parental figure, my guardian, is staunchly against the LGBTQIA+ community, and I’d be kicked out of the house for even doing this on stage,’” Ward said. “And that’s scary stuff.”

Having at least one person in their life “that believes in them” is “life changing,” said Tonya Jones, who, along with her wife, has fostered multiple LGBTQ+ youth in Pike County. Abuse from others simply for being different can lead to substance abuse or even homelessness if a child gets booted from their home by an unaccepting parent.

“It’s very hard for me to understand how people want to tell these kids they’re wrong for actually living their truth and living who they truly are,” Jones said.

Jones and her wife opened their home about four years ago. Her wife used to run a lawn care business that cut grass for multiple teachers who would tell her about local children “coming out to their parents and then being kicked out of the home and not having anywhere to go,” Jones said.

The importance of community

But finding community is essential, especially in a place where an accepting group of people hasn’t always been easy to find.

Members of Pikeville Pride know that well. The group started in 2017 as an organized counter protest to a white nationalist march in the city’s downtown. After that protest, about 20-25 people continued to meet, and decided to put together Pikeville’s first pride event in 2018 in an attempt to “highlight the diversity and inclusion that we actually do have here in Pikeville, that maybe people don’t realize,” Ellis said.

Jones, who was among the original group that started the organization, said they had a free hugs booth at the first event.

“I had someone just come up and just wrap their arms around me and just start bawling,” Jones said. “Because they said it was the first time anyone accepted them for who they truly were.”

They’ve held multiple pride events since including the booth at Hillbilly Days and pride proms. The 2023 celebration will be September 30 at the plaza at Appalachian Wireless Arena, the group’s largest venue yet.

Pikeville Pride also isn’t the only LGBTQ-focused group to crop up in the region in recent years. In 2018, TriPride held their first event in Johnson City, Tennessee, despite a small amount of protesters. Back in Kentucky, Ashland Pride got its start in 2019.

Ellis said she’s always struck by the amount of young people that attend the events. Many of them thank the Pikeville Pride folks for the event because “they finally feel represented.”

“I have a really joyous time, because it’s a celebration,” Ellis said. “But it also makes me cry, because I’m seeing the future tell us that they feel safe.”

When Ellis was in high school, she found community and role models in a lesbian couple who lived down the street. They were in their mid-to-late 20s, old enough to tell Ellis that despite the bullying, things will get better.

‘Very proudly, a hillbilly’

They also defied a common misconception that Ellis said she’s encountered in her work with Pikeville Pride. Many assume that those in the group have moved in from bigger cities and aren’t native Appalachians.

“It’s like, no, we’ve been born here,” Ellis said. “We’ve been raised here. We’re from here, we stay here.”

According to Jonathan Coleman — a historian and co-founder of the Faulkner Morgan Archive, a nonprofit that saves and shares Kentucky’s LGBTQ history — the typical narrative told about Eastern Kentucky is an incomplete one.

“The story of what it is to be queer in Eastern Kentucky is always a really flattened out simple narrative,” Coleman said. “You leave if you can, as soon as you can. You’re traumatized and then you try to escape. That, of course, is not accurate for lots and lots of folks.”

The story of Lige Clarke, a mid-20th century LGBTQ activist and journalist, flies in the face of that narrative, Coleman said. Clarke was born in and raised in Hindman. He would leave and much of his work — which included starting the first national LGBTQ newspaper in the wake of the famous Stonewall riots — never really forgot his hometown. His geographic identity informs “everything he does,” Coleman said.

Living and writing in the 70s from New York City’s Greenwich Village, the heart of the early gay liberation movement, Clarke was “very proudly, a hillbilly,” Coleman said. In multiple editorials, Clarke would expound on how he felt “a greater sense of sexual liberation in Hindman” than in New York.

“In Hindman his experience was one of much more fluidity when it came to sexuality, that even the modern gay liberation movement as it was going on (at the time), was forcing people into channels that were unnatural,” said Coleman, who wrote an article on Clarke for the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. “And that a true sexual revolution would be a sexual revolution for everybody. So pretty forward thinking.”

Clarke, whose work spanned multiple books and writings, was murdered in Mexico under mysterious circumstances in 1975. He was buried in Hindman.

Appalachia’s LGBTQ history has also been one of struggle. In 1987, native Mike Sisco returned to his hometown of Williamson, West Virginia, after being diagnosed with AIDS. He swam in the public pool in Williamson, a small town which sits across the Tug Fork River from Kentucky’s Pike County. Sisco was already the subject of local gossip and panic set off at the pool and in the community. The town closed the pool and became a national flashpoint.

“I went through a social death,” Sisco told Oprah Winfrey, who came to Williamson to hold a contentious, televised town hall to discuss the issue. “I stayed in a backroom a lot of the times at my sister’s apartment. Pretty much laid around and wished that I could hurry up and die.”

Eastern Kentucky came into the national headlines in 2015 as well when then Rowan County clerk Kim Davis refused to sign the marriage licenses of same-sex couples following the U.S. Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage.

The continued coverage of Davis nationally speaks to the continued assumptions made about the region, Coleman said. Other county clerks in other states were doing similar things at the time, he said, “but they don’t get the national press that Kim Davis does.”

“I think part of that is simply, she is such an easily identifiable narrative,” Coleman said.

David Ermold and his now-husband David Moore, who were denied a license from Davis, are also Eastern Kentuckians.

“No one ever focuses on that fact,” Coleman said.

‘I want you to see that you can live.’

A Floyd County native, Carver grew up in the mountains and came out publicly while he was in college at Morehead State University. Carver was a research assistant to one of his French professors and went with her to conferences.

At one conference, she insisted that he meet several of her colleagues, which Carver said he soon realized were mostly older gay men. Carver asked her why she insisted on him meeting them.

“She said, ‘Because I want you to see that you can live. I want you to see that someday you can be an adult man and be gay,’” Carver said. “I’d never seen one and I think that’s what the role model aspect is.”

Emma Lowe, a 37-year-old transgender woman living in Pike County, said she’s hoping to be that sort of role model. Lowe has had graying hair since her mid 20s. While watching a video online of another transgender person with gray hair, she noticed a comment that elicited surprise at seeing a transgender person live that long.

“Young trans people just assume that they will not have that opportunity to live long enough to have gray hair,” said Lowe, who is also a member of Pikeville Pride. “It makes me want to show mine off more and let people know you can have support. You can survive. You can thrive.”

A 2022 study from UCLA’s Williams Institute estimates Kentucky’s adult transgender population to be about 17,700 — about 0.51% of the total adult population.

Fraley said he’d only seen older transgender people in videos online. The rise of anti-trans rhetoric nationally makes no sense to him because “we don’t harm anybody.”

He said he could see why some LGBTQ+ Eastern Kentuckians might want to leave the region, especially if they don’t have the support system he does in his family, which he said keeps him home.

What is missing in Eastern Kentucky is some sort of safe, physical space for the LGBTQ+ community to meet and exist, Lowe said. There isn’t necessarily a place where Lowe and her wife can simply hold hands and not get a few looks.

For Pikeville Pride and their parent nonprofit Big Sandy Safe Space, that is a long-term goal, Ellis said.

Sarah Ratliff, Pikeville Pride’s treasurer and a professor at the University of Pikeville, said it feels like they’re “getting somewhere.”

“I think we’re doing a good job of breaking some stereotypes and stigmas and showing that this is all we do,” Ratliff said. “You know, it’s not perverted. It’s not sexual. It’s not nudity, it’s none of that. It’s just, I’m gay.”