Lights out for multilateralism? Alarm as U.N. faces cash squeeze

By Emma Farge and Cecile Mantovani

GENEVA (Reuters) - During talks on disarmament at the U.N.'s Geneva headquarters last month, alarm bells went off in the chamber to indicate that delegates had infringed new cost-cutting rules that restrict the length of meetings.

Screens and microphones were also shut off, forcing ambassadors to shout their speeches across the hall as events became "chaotic, confusing and noisy", and some feared the lights would be next, according to one of several people present who described the scene to Reuters.

"I was really concerned about the lights," said the Pakistani chair, Ambassador Khalil Hashmi, who eventually managed to get a limited agreement after assembling participants in a huddle.

The disruptions - which have happened on at least two occasions - were the result of emergency measures to cut costs at U.N. centers such as Geneva and New York.

The cuts, now in their third month, are a response to a situation described by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as "extremely alarming".

The United Nations has a $768 million hole in its $2.85 billion 2019 general budget because 51 countries have not paid all their fees, including two big paymasters: the United States and Brazil. Both say they intend to pay most of their dues, but even if they do, arrears remain from past years and spill into future budgets.

"Cash deficits occur earlier in the year, linger longer and run deeper," said Guterres.

Diplomats and analysts say the cash crisis points to some states' weak commitment to multilateral diplomacy, as evidenced by the suspension of the Geneva-based World Trade Organization's top appeals court and U.N. climate talks in Madrid last week reaching only a limited deal.

France and Germany have launched an "Alliance for Multilateralism" to support the U.N. and other institutions.

Richard Gowan, a U.N. expert at the International Crisis Group think-tank, said cash shortages were a symptom of a broader "crisis of political confidence" in the institution. "Most U.N. members just aren't that bothered about the financial problems the organization faces," he said.

Ambassador Hashmi urged member states to pay their dues, saying important U.N. business should not be "held hostage" to financial constraints.

Some critics say the United Nations could spend less on perks and bloated, often tax-free, salaries for senior officials.

"There is huge waste in the U.N.," said Marc Limon, a former diplomat and Executive Director of Universal Rights Group. "Instead of focusing on the U.N. mandate ... the U.N. spends a lot of money on high salaries in many cases."

U.N. officials have said they are unwilling at this stage to cut permanent staff salaries and are focusing on cutting costs in other areas.

LIGHTS DIMMED

Built nearly 100 years ago to house the U.N.'s forerunner the League of Nations, Geneva's colossal Palais des Nations - the home of multilateralism - hosts thousands of meetings each year on everything from refugee rights to peace in Syria and is showing its age.

Telephone booths abound, its art deco facade is yellowing and a monument donated by the Woodrow Wilson Foundation needs treatment for corrosion. Switzerland is lending $800 million for works.

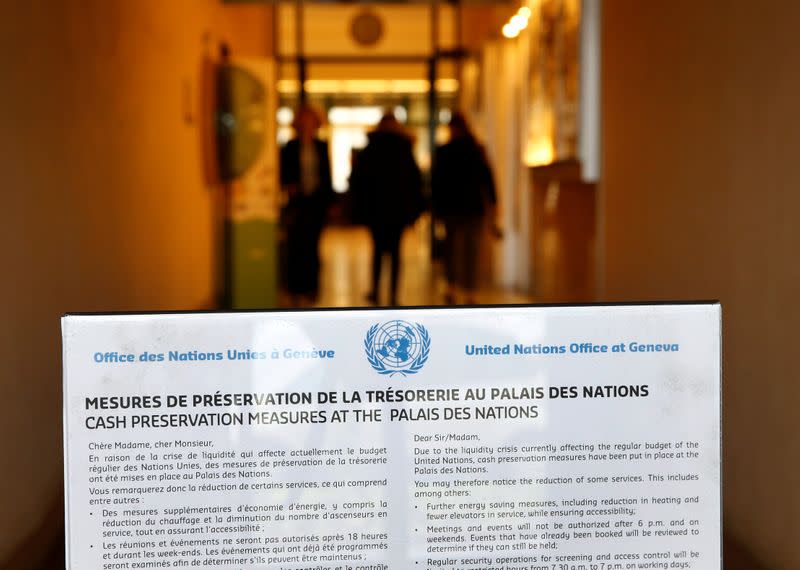

Corridor notices say the cash crisis has forced the closure of lifts and escalators. Hallway lights have been dimmed and some diplomats have brought in heaters as radiators have been dialed down despite the Swiss winter.

Nonetheless, a library exhibition celebrates 100 years of multilateralism since parades and fireworks first rang out in Geneva to celebrate the new "city of peace".

"The United Nations has been under pressure for many years to reduce its resources yet to deliver more. At one point it becomes very difficult," said Corinne Momal-Vanian, U.N. Geneva's director of conference management, who confirmed that meeting costs had been cut, for example, by using fewer interpreters and sound technicians.

Some speculate that cost-saving measures, thought to be making just small dents in the $14 million annual running costs for the Palais, are aimed more at annoying diplomats so they urge their capitals to pay up.

U.N. officials deny this and say savings are necessary.

Some critics question whether U.N. meetings such as deadlocked talks on nuclear weapons are worth pursuing at all, noting that any agreements get watered down by arms producers.

Mary Wareham, coordinator of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, described the process as zombie-like. "We are looking outside the U.N. to where the action is."

(Additional reporting by Michelle Nichols in New York, Cecile Mantovani in Geneva and Anthony Boadle in Brasilia; Editing by Giles Elgood)