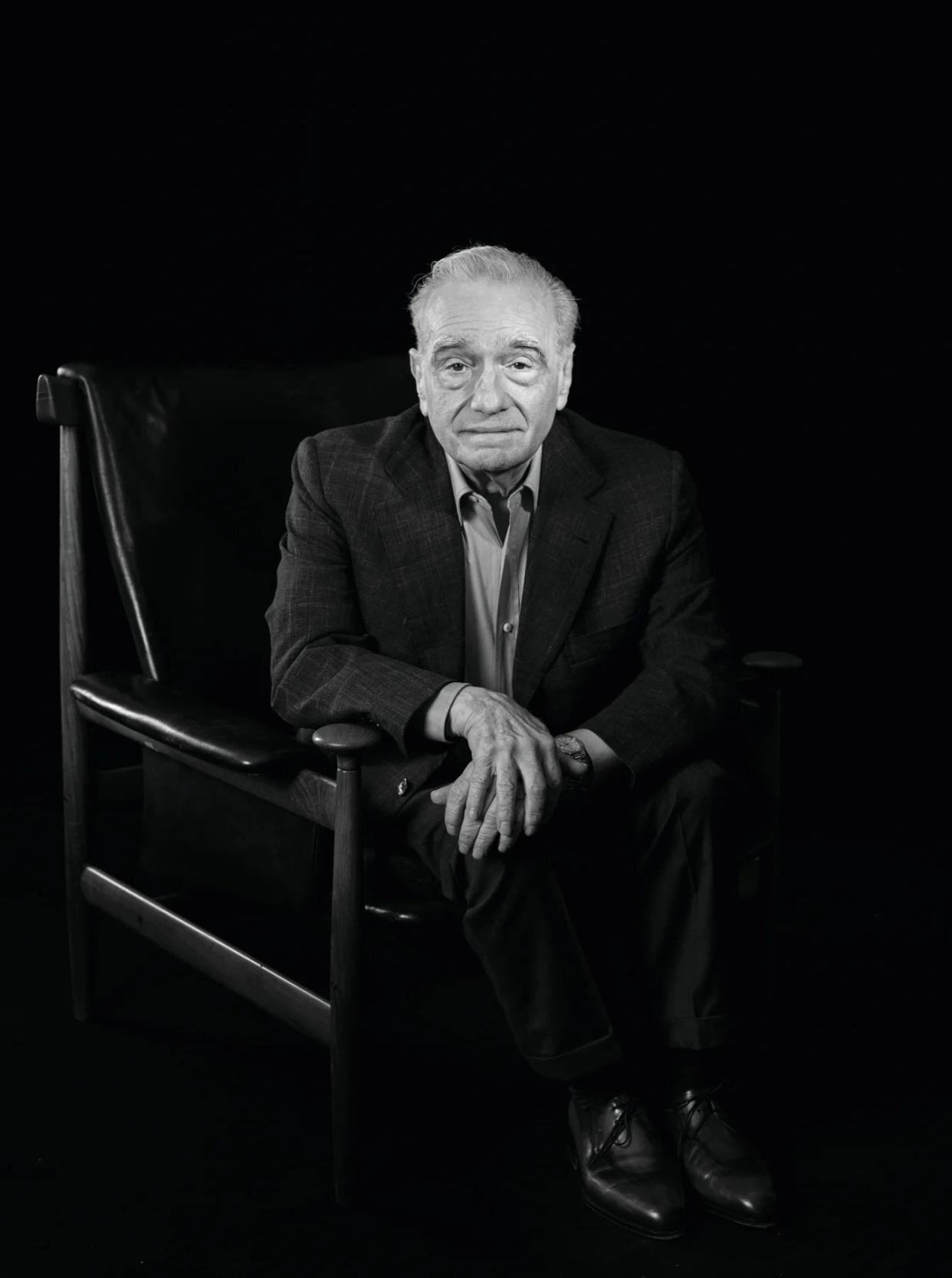

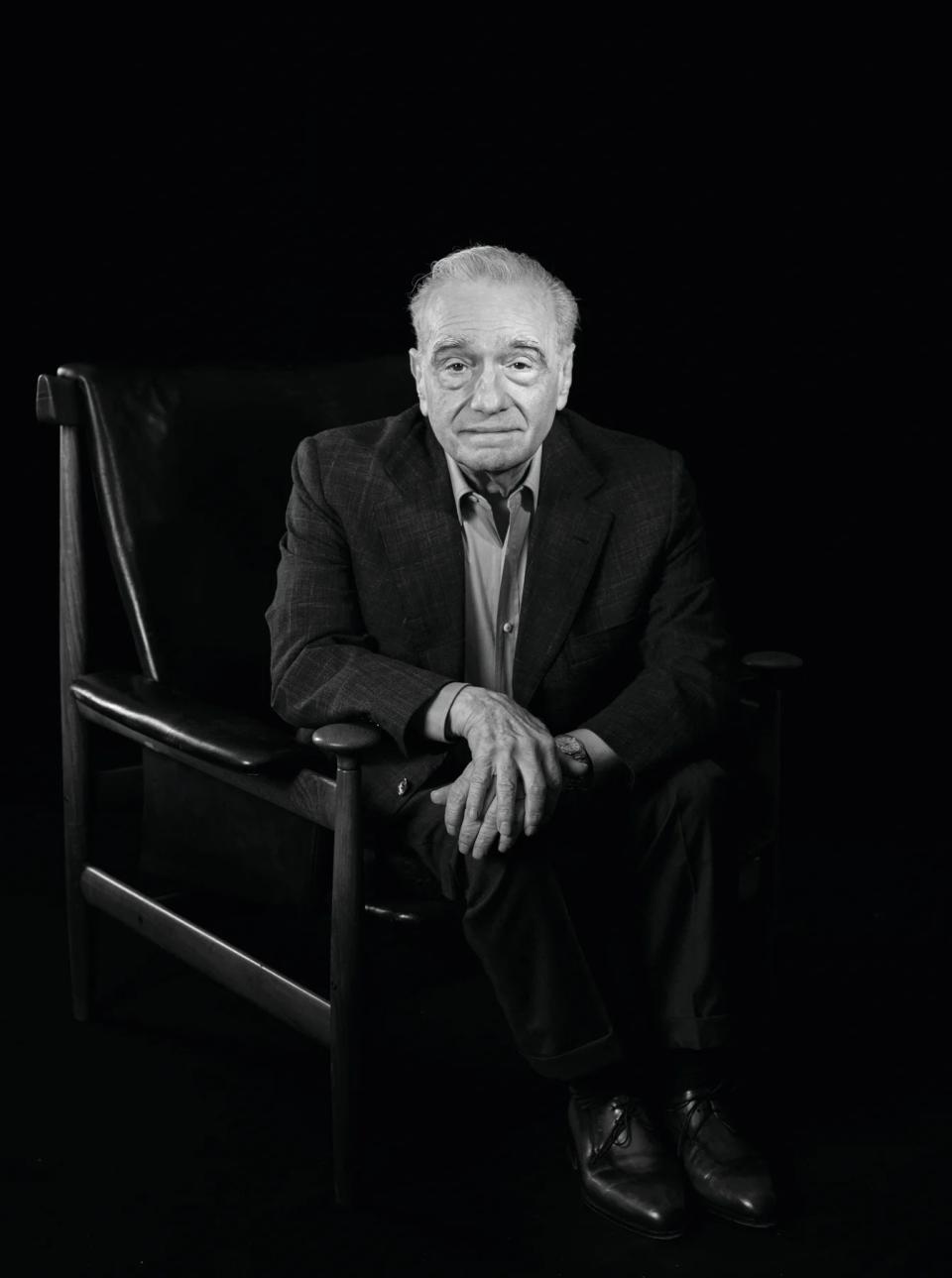

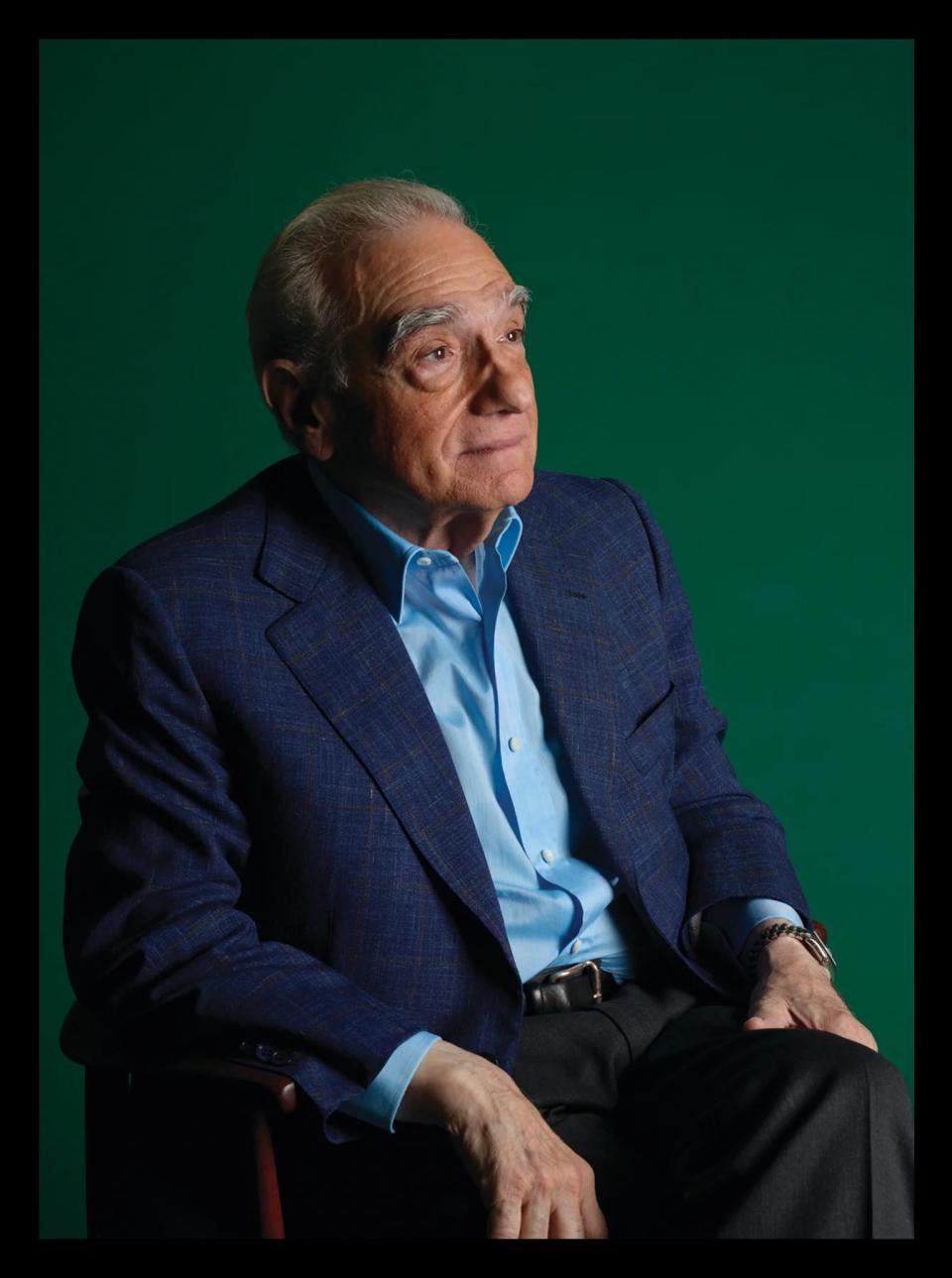

The Lion in Winter

Martin Scorsese figures he has one or two more movies left in him, but he’s making sure that the final act of his career is an epic one

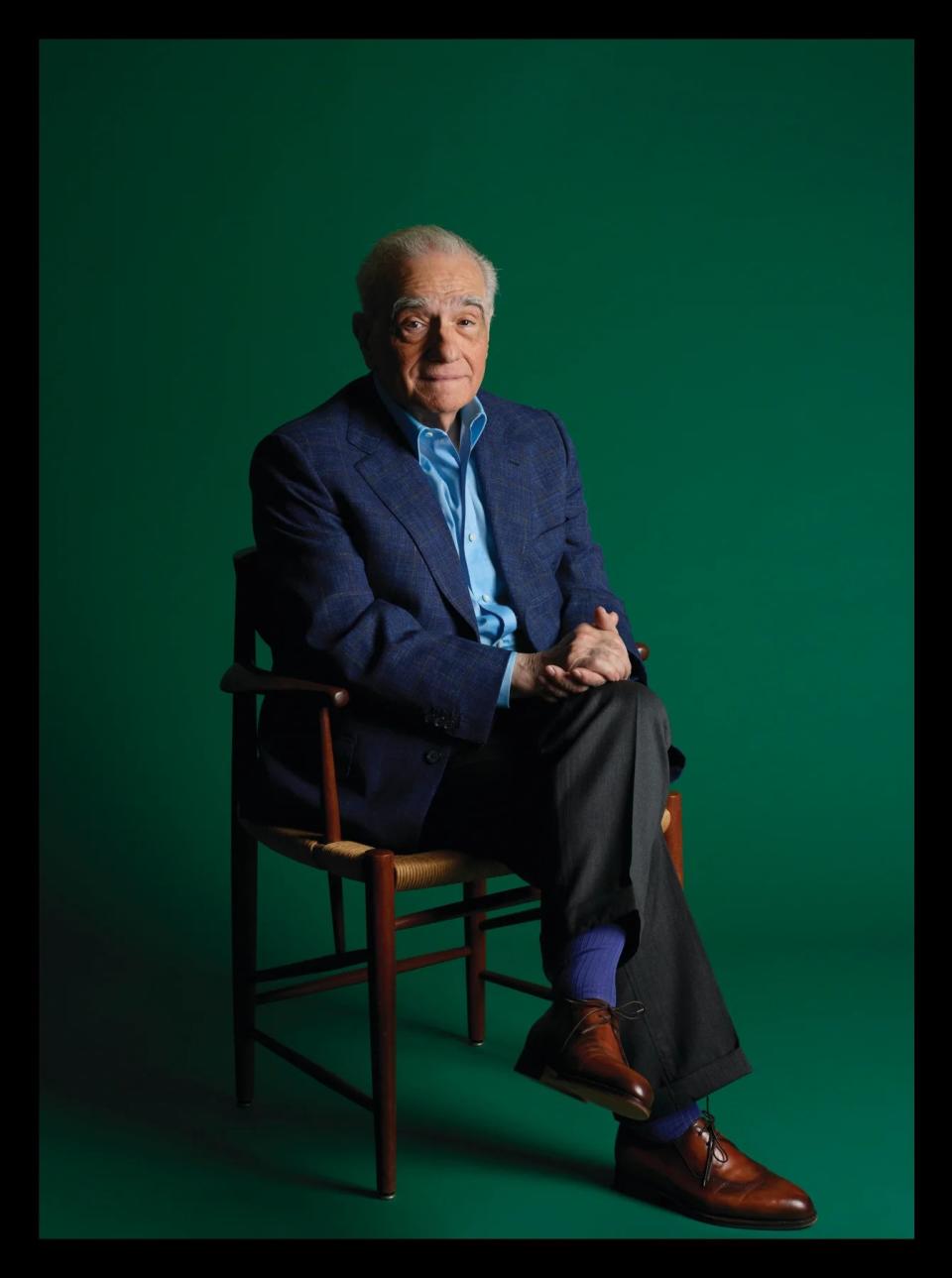

Photography by Catherine Opie

By Steve Pond

There was a time, and it doesn’t seem that long ago to some of us, when Martin Scorsese seemed to be a bundle of energy. Compact and wired, with a beard as black as the themes of many of his films, he cut a figure both brilliant and feral, and his movies hit hard both literally (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and figuratively (The King of Comedy, The Last Temptation of Christ). He was a quintessential member of the hot young directors who threatened to change Hollywood when they arrived in the late 1960s and early ’70s, and he remained the guy with a singularly fierce vision even when compadres like Spielberg and Lucas went full blockbuster.

The beard is now long gone, and the energy has dissipated. Scorsese turned 81 in November; he moves a little slower and tires a little faster, and there’s a sense that the people around him are working to conserve his energy. He’s matured into the guy we’ve known for years, the dapper New Yorker wearing a dark suit and sporting an authoritative air. But when he opens his mouth, the energy is still there as the astounding depth of his cinematic knowledge comes out in staccato sentences that swing through personal history and movie history simultaneously.

Case in point: Mention that his new film, Killers of the Flower Moon, is in a sense a Western, and you get five minutes on Marty and movies. “I grew up in the 1940s,” he begins, sitting in front of a picture window overlooking the canyons of the Bel Air neighborhood of Los Angeles, just up a winding road from the Bel Air Hotel where he typically stays when he’s in town. “I was born in ’42. With the asthma I had, I was not allowed to play sports or exert myself. So I went to the movies, and my experience of the outdoors was through the Western. I fell in love with that. Whether it was black and white or color, and particularly in color, it was extraordinary.”

Case in point: Mention that his new film, Killers of the Flower Moon, is in a sense a Western, and you get five minutes on Marty and movies. “I grew up in the 1940s,” he begins, sitting in front of a picture window overlooking the canyons of the Bel Air neighborhood of Los Angeles, just up a winding road from the Bel Air Hotel where he typically stays when he’s in town. “I was born in ’42.

With the asthma I had, I was not allowed to play sports or exert myself. So I went to the movies, and my experience of the outdoors was through the Western. I fell in love with that. Whether it was black and white or color, and particularly in color, it was extraordinary.”

He takes the briefest of pauses, then he revs up again. “I come from the generation that went through the best part of the Westerns, from 1945 to 1960 or ’62. And by ’68, the Westerns were over, with Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. So for me to even attempt to think of doing a Western after Hawks and Ford and Delmer Daves and Peckinpah, there was no place for me to go. It’s done. It was for that period of time and it was for that country and it was that for that world, you know? I may have been transported by them and I may have experienced certain truths and experienced life through them in the codification of the Western from the Hollywood system. But the world changed, and I was part of a new world.”

A shrug. “I don’t know if I could ever approach the Western that way. There were the modern Westerns, like The Getaway by Peckinpah, or what Terry Malick did, or Spielberg and The Sugarland Express, that sort of thing. I have a fascination for those, and I enjoyed doing Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in the Southwest back in 1974, ’75. I love that area. But I don’t know what the story would be. I don’t know what I could bring to it. But (Killers of the Flower Moon), there’s an oddness to it. Yes, one could say it’s a Western, but in reality, they have cars and airplanes they’re playing golf. I felt comfortable with that.”

But comfortable is not a word you’d ever associate with Martin Scorsese’s work, and certainly not his films over the last decade. Killers of the Flower Moon, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Lily Gladstone, is an expansive, relentless three-and-a-half-hour portrait of the methodical murders of dozens of Osage people for their money and oil rights in 1920s Oklahoma. Before that was The Irishman, which took the kind of gangsters who had populated Scorsese’s film for decades and forced them to look at the wreckage they’d created. Before that was Silence, a shattering two-hour-and-40-minute meditation on faith. Before that, he’d kicked off his 70s with The Wolf of Wall Street, which burst with the raucous energy of a director a fraction of his age.

For a director who’d demanded that Hollywood notice him in the 1970s with the one-two punch of Mean Streets and Taxi Driver and who’d entered the pantheon with a string of classics that includes Raging Bull, The King of Comedy, Goodfellas, Casino and whatever else you want to drop into that list, this final (?) act of his career has been an epic one. And he’s done it with a freewheeling sense of play, too, mixing in the HBO series Vinyl and documentaries about George Harrison, the New York Review of Books, David Johansen and Bob Dylan. The last of those, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, was a cheeky extended prank: Scorsese used footage from Dylan’s 1976 tour to construct a largely fictional story, but most viewers and reviewers assumed that because it looked and felt like a documentary and because it came from Martin Freakin’ Scorsese, it was true. (The Oscars even accepted it as a documentary, though they saved themselves some embarrassment by not nominating it as one.)

That’s Scorsese: an elder statesman with the credibility to do whatever he wants, but also a restless spirit who won’t stay in his lane. “Marty’s made two movies about me,” said author Fran Lebowitz, the subject of Public Speaking in 2010 and the series Pretend It’s a City in 2021. “And in the interim, he made 10 giant movies with casts of millions all over the world.”

She’s exaggerating: In the interim between the two Lebowitz docs, Scorsese made five giant movies with casts that probably only hit four figures. But she’s probably right when she explains why he returns to chronicling her acerbic thoughts on modern civilization: “Marty prefers to be in New York, so I’m guessing that’s why he likes to do things with me.” Not that the streets of New York City are the safest place for Scorsese. “Marty hates to be recognized,” Lebowitz says. “And he always is recognized. He wanted to shoot (Pretend It’s a City) in the street, and I said, ‘Marty, we won’t get 10 feet without someone stopping us.’ I only remember Marty being there once when we were shooting in the street. It was an extremely cold day and we were shooting in Soho, and within nine seconds, Marty was literally hiding in the doorway because people had noticed him.”

The changes in location, subject and tone are characteristic of Scorsese, according to Thelma Schoonmaker, who’s been editing his films since Who’s That Knocking at My Door in 1967 and who has nine Oscar nominations and three wins, both records, all for films she made with him. (One of her nominations is for the 1970 concert documentary Woodstock; Scorsese didn’t direct that film, but he was one of seven credited editors.) “He doesn’t want to repeat himself,” she says. “Almost all of his films are new challenges—but he’s so good, Marty, that he rarely does anything that doesn’t work.”

According to Jonah Hill, who was Oscar-nominated for The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese’s secret weapon is that when something doesn’t work, he knows how to fix it. “If you asked me the most impressive thing about Martin Scorsese as a director, which I’ve never seen even a millionth of from another director, there could be a shot or scene completely not working,” he says. “It could be an utter disaster, a complicated camera move or the acting or whatever. And while another good or great director would need to think intensely for an hour to figure out this massive problem, he fixes it quickly and efficiently. I’ve never seen anything like it. And then it works as beautifully as you’ve ever seen a scene work.”

Sometimes, Hill adds, Scorsese does that without seeming to do anything. “I was doing a phone booth scene one day, and he kept saying, ‘Do it again, do it again.’ I did it for about an hour. I don’t even know how many takes. I started getting a small anxiety attack because he’s not saying what to change and I don’t know what to do differently. And finally, his assistant comes up to me and says, ‘Jonah, are you OK?’ which then spirals me a million times deeper into my anxiety attack, because it means that everyone is noticing that I’m not nailing it. So my performance gets worse and worse.”

Eventually, he said, Scorsese stepped in. “He goes, ‘We’re going to take a break. Everyone step off the set. Kid, come here.’ And we go to his monitor, and he says, ‘Sit here.’ I sit down next to him and he just starts reading the paper for about 20 minutes. Doesn’t say anything to me. I sit there for 20 minutes, go through every range of emotion, and I finally just start to relax. Then he goes, ‘All right, kid, let’s try one.’ We do one, and it’s the take that’s in the movie.”

Hill still isn’t quite sure what happened. “I always think about, what was he trying to do?” he says. “And I guess it was, don’t think about the other people, don’t think about it’s not going right. Just relax and take a minute. You’re free to be good here.’”

For years, Martin Scorsese has been a voice in support of film, from his nonprofit film preservation organization the Film Foundation to his viral takes lamenting the Marvelization of the theatrical industry. But his recent work also finds him facing the inevitable: After decades of making films for major studios, he turned to streamers to find companies willing to bankroll his last two projects, both of which cost in the neighborhood of $200 million. Netflix backed and released The Irishman in 2019, and Apple did the same for Killers of the Flower Moon. And during the last 12 years, one of film’s greatest champions has also done work for HBO (George Harrison: Living in the Material World, The 50 Year Argument, the series Vinyl), Showtime (Personality Crisis: One Night Only) and Netflix (Pretend It’s a City, Rolling Thunder Revue).

It begs the question: Is there a place for him in the Hollywood studio system these days?

“No, I don’t think so,” Scorsese says without a pause. “First of all, I’m 81. If I’m lucky, I’ve got one or two more pictures that I can make. What are they gonna do with me at this point? The studios today, what are they interested in making? Can I fit in there? Honestly, I don’t think so.”

A shrug. “If a studio comes around and says, ‘We’d like to make something and give you creative freedom’—within the parameters of budget and length, et cetera, of course—I might go with it. But I would need the freedom. That’s all.”

Then again, you could probably go back 50 years, to when Scorsese had made Boxcar Bertha and Mean Streets and was about to begin work on Taxi Driver, and say that he didn’t really fit into the studio system then, either.

“Never did,” he says. “No. Even then, I was always an outsider. I wanted to belong, but I never belonged in that sense. I just didn’t. So you learn to accept that it’s all right to be an outsider.” He laughs. “And we worked together with some great people at certain studios over the years. Some people believed in what I was doing. There was Tom Pollock over at Universal, Brad Grey at Paramount. At UA it was Mike Medavoy and Eric Pleskow, and John Kelly at Warners, Terry Semel with Goodfellas… I was very lucky, you know?”

The luck held into the 2000s, by which point had enough clout to continue making his movies his way. He finally got his Best Director and Best Picture Oscars for 2006’s The Departed (part consolation prize for not getting it for Raging Bull or Goodfellas, you could argue), and he followed that with a couple of genre exercises: Shutter Island was a brain-teasing thriller with a nice twist, Hugo an adaptation of a children’s book that also served as a love letter to early cinema and a way for Scorsese to explore 3-D. (Forget about the expansive glories of Avatar—if you want a jaw-droppingly great 3-D shot, try the closeup of Sacha Baron Cohen’s face in Hugo, with his nose seemingly reaching into viewers’ laps.)

At that point, Scorsese seemed to be flitting here and there creatively, looking for sparks. Then came the wake-up call: The Wolf of Wall Street, an uproariously excessive black comedy about real-life stockbroker and convicted fraudster Jordan Belfort. People compared it to Goodfellas and Casino in its depiction of bad people behaving badly, but Wolf embraced moral ambiguity and made depravity fun. “It’s another look at America, another look at who we are,” Scorsese says of the comparisons. “I was hoping I could develop the style and push it further, so I just decided to go big. I told Thelma, ‘I want it ferocious. I want an attack.’”

His films since then haven’t been as ferocious or assaultive, but they’ve been every bit as epic; it’s as if, with a limited number of films left to make, Scorsese isn’t interested in genre exercises or amusing flicks. He wants epics. (Is it any surprise that he recently said his next movie will be an adaptation of the Shūsaku Endō novel A Life of Jesus?)

“That happened organically,” he says. “I didn’t intend it. I think once I got involved with the subject matter, I found myself creating worlds, so to speak—universes, maybe—that needed this time or this size. I didn’t plan it that way. I didn’t say, ‘We’re gonna make a 15-hour epic.’ But once I got into Wolf of Wall Street or even Silence, I became appreciative of the immersion into those worlds. And I thought we should take the time.”

He grins. “I know now everybody has TikTok and everybody is moving around real fast. But you go to a movie theater, maybe see this on a big screen with an audience you know, you feel it.”

He thinks about it a little more and realizes that maybe he’s overstated the case with all those “I didn’t plan it” declarations.

“I think in Wolf we did plan to make a sweeping epic of greed and lust and bad goings on,” he admits with a laugh. “I wanted to show flat-out what it is. And, you know, I think that taking advantage of the Osage is directly in line with Wolf of Wall Street. If that’s who we are, that has to change.”

For Scorsese, the road into Killers of the Flower Moon began by trying to find a way into the story told in David Grann’s nonfiction book about the Osage murders. It wasn’t hard. “I’m from another culture, an urban culture,” he says. “I found that in the behavior of the European Americans, the white people in Oklahoma, there’s a constant that streams through our culture, which is: Take as much as you can, win as much as you can. Winning is better than losing. Taking is better than giving. If you have this new land with these new resources, take as much as you can. If some people are in the way, work out a deal. If they can’t work out a deal, put ‘em in their place. If they can’t stay in their place, kill ‘em. Simple. It’s all for the sake of this new world that we’re creating, right? I felt that I could identify with that.”

The story underwent significant changes through an extended preproduction that included COVID delays and a rewrite when DiCaprio switched roles from a federal agent investigating the murders to Ernest Burkhardt, a World War I vet who marries Gladstone’s Mollie Kyle and may be wrapped up in her poisoning and the murder of her family. “Did he accept it or did he just embrace his delusion, his denial?” Scorsese says of Burkhardt. “Those scenes were like walking a tightrope. And it was the same with her. Did she think that he was involved? She knew that he was a roustabout, so to speak, and that he was under the influence of King Bill Hale (De Niro), but did she ever think he would betray her? And I’m not talking about betraying her with women or drinking or getting in trouble. I’m talking about serious betrayal of the heart to the point where he could kill her.”

Eventually, he decided that both people were probably in denial. “Love wipes away the truth,” he says. “I learned from the Osage people that Margie Burkhart, the great-granddaughter of Ernest and Mollie, said they were in love. This is not a matter necessarily of villain and victim. It isn’t that simple.”

Scorsese’s embrace of sources within the Osage community continued throughout the production and was one of the reasons why the indigenous actors in Killers were comfortable working on the film. “The great thing is that Marty had no interest in trying to be right, or trying to change Osage views and Osage concepts to whatever his concept was,” says Gladstone, an indigenous actress from the Blackfeet nation who has won numerous best-actress awards for her performance. “He was eager to bend whatever his thought might have been if there was something better. And there was always something better if it was coming from the Osage.”

Scorsese agrees. “(Cowriter) Eric Roth and I had to get it right,” he says. “It had to be as accurate, as authentic as possible. We had all our consultants and they kept us on the straight and narrow and also contributed a lot. They would walk by and say something and we’d say, ‘Let’s put that in.’” One particular scene that changed dramatically came when Ernest visits Mollie when a thunderstorm hits. The script had them doing shots and Mollie drinking Ernest under the table as the storm rages, but that was changed to a gentle sequence in which she tells him to sit quietly and feel the power of the deluge. “The idea of a thunderstorm being a gift from God came from one of the Osage guys who’s a lawyer,” Scorsese said. “He said he didn’t understand what was going on in the scene, and then he said, ‘Just experience the storm.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s great.’”

Even with its input from Osage and other indigenous people, Killers has been criticized for telling the story of the Osage murders from the perspective of the perpetrators rather than the victims; it’s part of a larger conversation about who has the right to tell stories, particularly if they’re coming from groups that traditionally have not had platforms on which to tell their own stories. In a way, the film acknowledges this point in its final sequence, which recaps the murders through the staging of a radio play being put on by white people many years later. “This is how the story has been told,” the scene essentially says—and then Scorsese himself appears onscreen as a radio announcer who sums up Mollie’s fate. If nothing else, it’s an acknowledgment that once again, we’ve had an indigenous story being told by perpetrators and outsiders, including the dapper outsider who gives himself the last words.

“Absolutely,” Scorsese says of that scene. “I felt something, and I felt I should say it. I didn’t know how to direct the last lines of the picture, so I said, I’d better try it myself. It’s my own sense of atonement, I guess, on one level. I just felt it was right.”

In a way, it’s also a retort to the argument made in some circles that it’s damaging to teach the dark side of American history. Killers, and indeed many of Scorsese’s films since the 1970s, make a counter-argument that you have to acknowledge those things, put them on screen and face them.

“It’s like hiding the secrets in the house,” he says. “At some point, when it does come out, it’s gonna be too traumatic. Why don’t we just say the truth, or at least give the facts of what happened? Then you could say, ‘Why did it happen? Why did Nazism rise in Germany after World War I? How did it happen? How did they allow it to happen? How did fascism begin with Mussolini in Italy, and what tradition are they coming from?’

“This is another world, but it can happen here and it may be happening here. So the more we learn about even the unpleasant truths, we can work on a new world. We can make it different. How could you make up for the terrorism, the horrors that occurred? You do that by respecting people, giving them the dignity they deserve and the love, if you can. And maybe by acknowledging the past, as unpleasant as it is, we can make a change in the future. Hiding, it’s not gonna go away. It’s gonna get worse when it comes out.”

The post The Lion in Winter appeared first on TheWrap.