Long hours, emotional toll pushed tissue bank specialist to leave province

During her time as a certified tissue bank specialist in New Brunswick, Parise Léger commonly worked more than 30 hours in a stretch.

At one point, Léger said, she was one of only two specialists assigned to collect tissue donations, such as bones, tendons, heart valves and occasionally corneas, from anywhere in the province.

But after four years on the job, the long hours and emotionally draining work drove Léger to leave the province and her job with the New Brunswick organ and tissue program in 2017.

She's now speaking out after hearing the story of 16-year-old Avery Astle, who died following an Easter long weekend crash.

His parents wanted to donate his organs and tissues, especially his blue eyes, but said they were told no one was available to facilitate the donation at Moncton Hospital.

"I was heartbroken," said Léger, who now lives in Nova Scotia.

But according to Léger, it's not a recent problem. It's one she flagged to management at Horizon Health Network as recently as 2016.

"It's unfortunate that it's still happening in 2019, when the province was made aware that there was a staff shortage and a big problem in New Brunswick when it came to the tissue division."

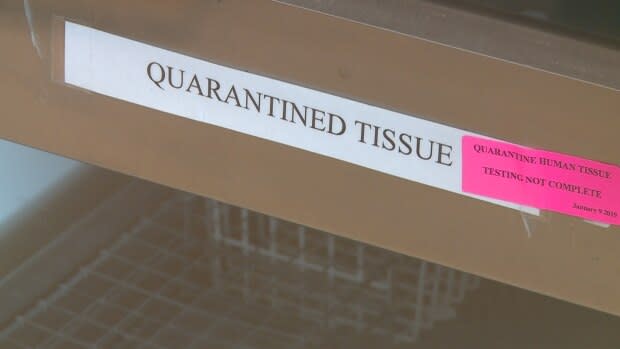

Last week, Horizon said there are gaps in its tissue donation coverage, citing "recent turnover within the tissue team." The gap doesn't affect its organ donation team, which is a separate division of the program.

"Until our newly recruited team members have been fully trained, there may be times when we are unable to provide the service," the health authority said in a written statement.

Long hours on the road

Léger said the tissue team, which is primarily based in Moncton, was rarely fully staffed at four during her four years on the job.

The staffing problems were brought up "numerous times" to management in Horizon, but according to Léger, nothing changed. She said the program should have had enough staff to cover 30 days, while also allowing those staff members to have a work-life balance.

Léger estimated this would have required six to eight staff to cover the whole province, so it wouldn't just be the same staff members on call all the time.

As a specialist on the tissue team, Léger was required to take nearly two years of training to be certified by the American Association of Tissue Banks.

Her job usually consisted of working four days in the office, working on charts or processing tissue donations. Then she would be on call for 20 to 22 days on average.

After a death was reported, the tissue team would be called in if the person qualified for tissue donation. The person on call would then call a nurse and go through the chain of events leading to the death to learn more about the donor's eligibility, Léger said.

"From then on, if they (the donor) qualify, we would contact the family and obtain consent," Léger said.

It could mean travelling from her home in Moncton to as far away as Edmundston on a moment's notice, then spending hours with families or in the operating room, collecting tissues.

Typically, Horizon Health Network would pay for a car to drive the technician if they were going more than an hour or two away and had already worked long hours.

A 'complex' problem

Last week, New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs questioned whether it's possible to have round-the-clock donation service across the province.

"I don't think it's realistic to say it's possible all over the province, 24/7, but I don't know that for a fact," Higgs said.

"But I have asked, we've had the discussions, [Health Minister Ted Flemming] wants to understand it as well and he's asked the department to understand."

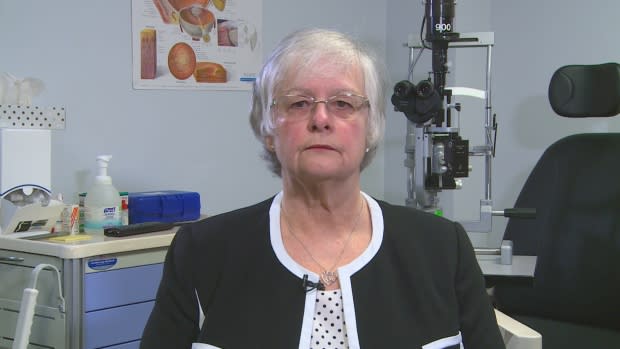

It's a question Mary Gatien wrestled with as director of the New Brunswick Organ and Tissue Program, a job she retired from last year after 25 years.

"Under the current staffing, and the model that most banks have, to every person in the province it's probably not realistic," said Gatien, now a quality consultant with the ocular division of the program.

According to Gatien, the program struggles with both retention and funding. Training someone to be a specialist can take upwards of 18 months.

But the nature of the job coupled with long hours make keeping those employees challenging.

"You can put a lot of money into the program, but it does not guarantee staff retention," she said.

Neither Gatien nor Horizon Health Network could provide details on the program's current budget before deadline.

You could have technicians working as nurses in the hospital and then pull them off the floor when there's a potential donor, but that would leave the hospital short-staffed, Gatien said.

But having someone dedicated to collection full time could also be challenging in small or rural hospitals, where days might pass before there's a potential donor.

"To pay an RN, it's $90,000, so if they're in a small hospital and they're dedicated to this, what do they do when there's no donor?" Gatien said.

Donors could also be processed in one central area, which could make things simpler for staffing, but not everyone would want to have loved ones moved to another area. Plus, according to Gatien, the transport could affect the quality of the tissue.

"It's a very complex situation and it's a complex problem," she said.

Gatien said the current gap opened after the retirement of several senior staff members. Horizon Health Network could not provide the number of times someone has wanted to donate tissue and no one was available to collect it.

The current director of the program was not made available for an interview.

A mental toll

While the job could be physically exhausting, it also took a mental toll on Léger.

The job involved talking to families "on their worst day." Sometimes they were still in shock, she said.

"Sometimes, you're the first person that they talk to, they haven't talked to family yet," Léger said.

There wasn't always an opportunity to debrief after each donation, Léger said, so the tissue team members relied on each other for support.

Léger said her breaking point came at the end of 2016, when her family and friends started noticing the toll it was taking on her. She was always on the road and "always tired." She decided to take her health into her own hands.

"Coming back in January, I just found that I was stressed to the point of being burned out," she said.

"I went to see my family physician and I went on sick leave for a couple months."

She gave her notice to leave her job in April 2017, moving to Ontario to take a job with the Trillium Gift of Life Network.

Now in Dartmouth, N.S., she's no longer working in tissue donation. But she continues to be passionate about the issue, and would like to see the province add more funding to the program.

Léger said she was "speechless" to hear the premier question whether it's realistic to have round-the-clock coverage.

"When we're talking about no coverage on holidays and long weekends, it's a huge problem," she said.

"I think that there should be coverage 365 days of the year."

While tissue donations aren't necessarily life saving, like an organ donation, they can change a person's life, Gatien said.

A tissue transplant could reduce pain and increase mobility for someone who has been in a car accident, or who has a hip replacement or torn the ACL, a key ligament that stabilizes the knee, for example.

"It is, and I'll quote a family, a feeling that cannot be put in words," Gatien said.