Look up: How the Sistine Chapel changed this Canadian author's life

Even if you make it to Rome, it's no easy feat to get a glimpse of the most celebrated ceiling in the Western world: the Sistine Chapel.

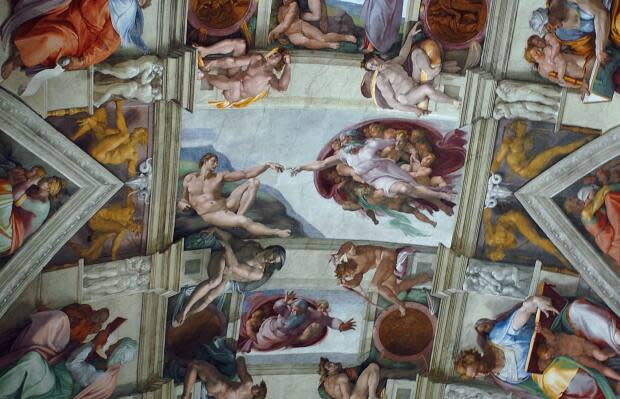

The Renaissance artistic tour de force, painstakingly painted by Michelangelo in the early 16th century, is the final showcase of the vast and masterpiece-laden Vatican Museums. But first you have to get in — and tickets can be hard to come by. Lineups wind under an unrelenting sun and the press of sweaty tourists is overwhelming.

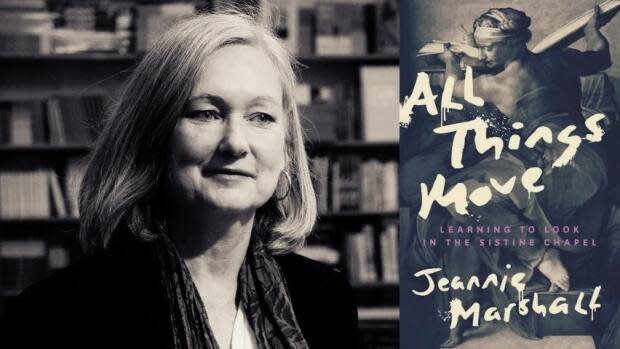

For years, Canadian writer Jeannie Marshall, who has lived in the Eternal City for two decades, stayed away. Mostly she was turned off by the crowds, but also because the Sistine Chapel is both complicated and obscure — too difficult to unravel in just one view — and overexposed.

"There are people with a religious interest who come to see it, but it's just one of the things you do on the tourist trail and you feel guilty if you come to Rome and don't see it," she said. "It's in guidebooks … like the Mona Lisa or The Last Supper."

Then, a decade after moving to Rome, Marshall's mother, a believing but resentful Catholic from Ontario, died. And something in Marshall, who is not religious, shifted.

Inexplicably, she found herself putting up with the crowds and standing under the dazzling array of Biblical scenes painted above her: God's finger reaching out to Adam's, infusing him with life; Adam and Eve being chased from the Garden of Eden; Jesus separating the saved from the damned; and the scene that first captivated her, Noah and the flood, otherwise known as The Deluge.

"I realized what was going on in the painting was not what I thought," said Marshall. "These are not survivors, but people who are pulling themselves out of rising floodwaters and they're going to drown. And the ark is floating away."

The modern relevance of the painting, with sea levels rising due to climate change, and the details Michelangelo included in the scene — such as a woman trying to get out of the water with a table balanced on her head — intimate a profound empathy Michelangelo had for those not saved by the ark. They moved Marshall to return.

Over the next decade, she visited the Sistine Chapel some 30 times, to look at, think and write about the religious masterpiece. Her observations and reflections, focused on the core question of why art moves us, are explored in her new book, All Things Move: Learning to Look in the Sistine Chapel.

"I'm not trying to pretend that I'm a scholar," said Marshall. "But I feel that art, in particular, is something for everyone. Anyone can be an artist, so why can't anyone think about it, contemplate it and write about it, rather than only critics and experts?"

Marshall may not be an art historian, but she nonetheless elegantly sets the Sistine Chapel in historical context, speculating about theological, philosophical and political influences on Michelangelo, describing his own transformation as Martin Luther began speaking out against the hypocrisy of the Catholic hierarchy, lighting the spark of the Protestant reformation.

Marshall also weaves throughout the book reflections about how our individual, private past informs our reaction to art.

Indeed, there's a long history of art eliciting overwhelming emotions in people. Thinkers and writers such Goethe, Simone Weil, Stendhal and many others have explored the ecstasy and dread that works of art provoked in them.

In the 1970s, Florentine psychiatrist Graziella Magherini coined a term for the mini-breakdowns tourists sometimes experience when faced with art: Stendhal syndrome. The panic attacks, she argued, were proof of the powerful connection between art and our psyches.

There are also the incidents of museum visitors who impulsively slash, smear or throw objects at priceless works of art.

"I've had strong reactions myself to some pieces of art and have never wanted to damage something. But sometimes I've been surprised at the level of feeling I might have, be it irritation or or great sadness in front of a piece of art," said Marshall.

"I don't know where it comes from exactly, but I grew up in an environment where there was a lot of anger, places that were somewhat impoverished and where people had a feeling of futility."

As Marshall began to write about her experience of the Sistine Chapel, to her surprise, connections emerged between her own past and the Michelangelo masterpiece.

Before Marshall's mother died, she revealed to her daughter, the youngest of nine children, that for complicated reasons, she had not been able to marry her children's father, who died when Marshall was a baby. Her mother, a faithful Catholic, had carried a lifetime of secret shame.

In her reflections on the history of the Sistine Chapel, Marshall writes about the 25-year-period between Michelangelo painting the ceiling and the altar wall, when a mercenary army sacked Rome, raping, pillaging and murdering. Part of that army's rage was fuelled by the writings of Martin Luther, who called out the Catholic Church for funding extravagant works of art in Rome by selling indulgences to peasants in northern Europe.

Michelangelo himself felt implicated. The touches of playfulness, like depicting God in the same position he assumed while painting, flashing his naked bum at viewers below – are absent from the altar wall, painted after the sack. There, Michelangelo places himself on the side of the damned.

In her book, Marshall also outlines an underground emotional conduit joining that explosive anger from 500 years ago, her mother's rage and her own unexpected feelings triggered by religious art.

"Everything fell apart if I didn't have the story of my mother and her relationship to Catholicism in the book," she said. "You don't necessarily interpret the link between your past and art it in a logical way.

"So sometimes you have to stand there and think, 'Why am I having this reaction? Why do I feel the way I do?' Even just the numerous images of Mary and the child in Rome. Why do some of them make me upset?"

As a non-believer, Marshall could have chosen any number of famous masterpieces to use as a launching canvas, so to speak, into her philosophic probing of the meaning of art. So why did she choose the most monumental Catholic one?

"It's a question I ask myself as well," said Marshall. "I think it's because as I was unravelling what the art itself meant, I realized that it was so connected to my mother's own problems with Catholicism. How she loved so much about it — all of the rituals and the art work — but also felt it oppressed her as a woman."

That feeling of oppression and rage at the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church have simmered — and at times, erupted — throughout the Church's history.

And Marshall says if you take the time to look — and look again — at the astonishing beauty, movement and mastery of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, you can even get a glimpse of it there.