As luxury apartments spring up in Garden City, some homeowners get displaced

Gary Gallipeau is running out of time to find a new place to live — forced to leave a rare affordable housing option to make way for another big development near the Boise River.

“It’s frustrating, stressful,” Gallipeau told the Idaho Statesman. “It’s making me sick.”

Even with high interest rates, expensive materials and a labor shortage, longtime residents of some areas of the Treasure Valley are being forced to move as the region continues to see a torrent of new hotels, office buildings and apartment complexes go up.

That includes Garden City, where property along the Boise River has become developer catnip as luxury housing like the 138-unit Boardwalk Apartments have taken positions along, or near, the Greenbelt.

The Boardwalk is not the only one. The city has approved several proposals for apartments and town houses along or near the Greenbelt, from roughly 39th Street to 43rd Street, in the past year.

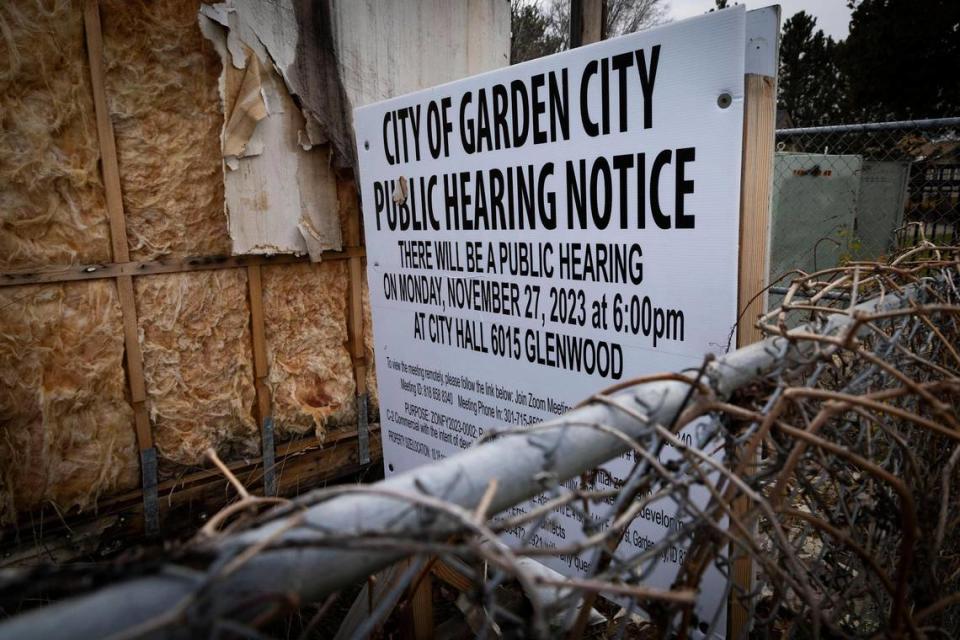

And many of these developments sit on the site of a former, or soon-to-be former, mobile home park such as the Dee Mar Mobile Home Park at 411 E. 43rd St. in Garden City.

That’s where Gallipeau has lived for nearly 14 years.

The last remaining residents of the 20-unit park are scrambling to leave with a Dec. 31 deadline to vacate before Vida Properties, the developer, converts the property into a five-story, 90-unit luxury housing development called Dee Mar Apartments. Vida Properties also developed the Boardwalk.

When Chop It Up Investments LLC bought the land under the park in 2019, many of the residents, who own their homes, knew redevelopment could come eventually.

That day arrived in January, when the company gave residents a 180-day notice to vacate the property — either by moving their trailers or by moving out. The company extended the deadline twice, with the final date set for Dec. 31.

Gallipeau still lives at the park and doesn’t know where he’ll go or what will happen when the deadline arrives.

“The whole thing sucks, just to put it in plain English,” Gallipeau said.

Owners of mobile homes seek help to vacate

Gallipeau, who lives with his fiancee, said Chop It Up Investments sent him a letter when the development was announced that indicated it would help move the trailers and provide other concessions.

“(We) never saw any of those at all,” Gallipeau said.

Gallipeau and his fiancee are both disabled and live on fixed incomes. With little money to move his trailer, he has struggled to find a place for the two of them.

“My stance is not that I don’t want to leave, it’s just that I can’t until I can secure another place for us to live,” Gallipeau said.

According to Lori Dicaire, investigator for the Intermountain Fair Housing Council, or IFHC, many of the homes in Dee Mar were built before 1976 and need significant rehabilitation before residents can move them.

Dicaire and the Intermountain Fair Housing Council wrote three letters over the past year to Chop It Up Investments, Vida Properties and the city of Garden City asking for help for the park residents. The organization has heard nothing back, she said.

One request asked that the city or developer pay for some of the value of some of the residents’ homes.

“I’m not looking for a bunch of money. This trailer is not worth that much, but at least give me something,” Gallipeau said. “I mean I’ve never been a homeowner until I bought this trailer and I’ve been here for 14 years.”

Chop It Up Investments and Vida Properties did not return multiple phone calls requesting comment.

“There’s still a large expense ahead of me and they’re not willing to help us at all,” Gallipeau said. “So it is what it is. There’s nothing I can do about it.”

Mobile home options vanishing

The number of mobile homes in Garden City has been decreasing for years, Dicaire wrote in a letter submitted to the developers, owners and Garden City in October.

“According to the data provided by Garden City, IFHC has learned that an alarming rate of mobile home park closures has occurred in Garden City over the last 12 years,” she wrote. “Since 2011, 21 parks have closed, which represents over 180 units.”

The city’s 2019 comprehensive plan update, she wrote, showed mobile home units declined from 29% of the city’s housing stock in 2000 to 19% in 2016.

Dicaire told the Statesman that the demolition of mobile home parks takes away housing from some of the community’s most vulnerable residents, including seniors, veterans and those on fixed incomes, like Gallipeau.

“These are essential members of our community,” said Dicaire. “They are people who work in our businesses. They are longtime residents.”

According to Vanessa Fry, director and associate research professor at the Idaho Policy Institute at Boise State University, mobile home parks are one of the last naturally affordable housing options — meaning housing that is not subsidized by the government.

“As that type of housing goes away, we’re losing a tool in the toolbox for affordable housing options,” Fry said.

In some states, there’s policies in place where if the owner of land wants to sell, the residents have an opportunity to make a competitive offer for the land first, Fry said. Idaho has no such laws.

‘These are tough situations,’ mayor says

Garden City Mayor John Evans told the Statesman by phone that there’s not much he can do.

“We’ve got a park owner who chose to sell their property and retire,” Evans said. “We got a developer who bought the property who wants to do something else with it.”

The city is not in any position to help the residents of the park, he said.

“These are tough situations, but there’s a real risk if you own a mobile home and you rent a space on a month-to-month (basis),” Evans said.

Even though the park residents own their homes, Evans said, they did not have a legal standing to stay on the property if the new owners properly notified the residents. In this situation, residents would move from tenants to trespassers.

“With Dee Mar, the developer gave twice the notice that he was required to by law and the city … has no capability even if we wanted to mitigate the expense of folks that have to leave,” Evans said.

One resident of Dee Mar needed a waiver to move her trailer into a new park and Evans said the city granted that waiver. But forcing the developer to pay for the mobile homes like Gallipeau requested is out of the purview of the city, he said.

“There’s really not a mechanism for the city to force one party to give money to another party,” Evans said. “That’s beyond the reach of the city to rectify.”

In these circumstances, Evans said, the role of the city is to make sure that the new owners properly follow Idaho code for notifying residents — which he says the developers of the proposed Dee Mar Apartments did.

“People get trapped with these aging mobile homes, many of which can’t be moved,” Evans said. “The ground is sold out from under them. That’s where we try to rely on nonprofits and grants.”

Economics, real estate interests take over

The value of land and homes near the Boise River dramatically rose as demand increased throughout the Treasure Valley, Evans said.

According to the Ada County Assessor’s Office, the Dee Mar Mobile Home Park’s total assessed value was $704,500 in 2019. By 2023, the property sat at over $1.5 million.

Increasing demand and the rise in land prices has led to the replacement of mobile home parks with luxury listings, Evans said, rather than any concentrated effort by the city to attract apartments.

An additional factor in the demolition of these parks has come from the limited amount of space to work with as Boise entirely surrounds the city, he said.

“We don’t have green fields to expand into,” Evans said. “It’s going to be higher-density residential and mixed use.”

Much of the “dramatic rise in value” that Evans has seen occurs along Chinden Boulevard and the Boise River, with the most acute rise along the Greenbelt.

“You’ve got a finite circumstance there,” he said.

Few protections for mobile-home owners

There are few options for owners of mobile homes when the landowner wants to sell their property.

Leap Housing, a Boise-based nonprofit focused on helping vulnerable populations buy homes, offers one solution through ROC USA — a national nonprofit that helps form resident-owned communities, or ROCs.

The organizations help mobile home park residents organize and buy the land they live on together from willing sellers. Leap works to provide technical assistance to residents, negotiate between the two parties and secure financing for the deal.

The residents form a nonprofit cooperation and a volunteer board acts as the owner, said Holly Apsley, ROC program manager for Leap. Everyone who lives in the park and wants to join can become a member of the cooperation.

Idaho has two such resident-owned communities: one formed in Caldwell in 2019 and one in Garden City in 2020. The Garden City location combined two mobile home parks, Buddy Manor and Native Dancer, into one entity named Buddy Dancer near the Boardwalk development.

Getting rid of mobile homes, Apsley said, doesn’t help with the lack of affordable housing in the Treasure Valley.

“You can’t just add to your affordable housing stock if you’re losing a lot of it,” she said.

Mobile homes, she said, allow residents a space of their own and serve as a lower-cost option for those who can’t, or don’t want to, live in a luxury apartment. Despite a stigmatized perception, they contribute to filling the “missing middle housing” between single-family homes and apartments, Apsley said.

“To me, it’s a real happy medium in terms of density,” she said.

However, she noted that there are downsides to mobile homes. They’re difficult and expensive to move and paying rent on the dirt under them can lead to a precarious situation like what’s happening at Dee Mar Mobile Home Park.

When asked if there were any other protections for mobile home owners, Apsley’s answer was simple:

“No,” she said. “There’s not really anything else they can do.”