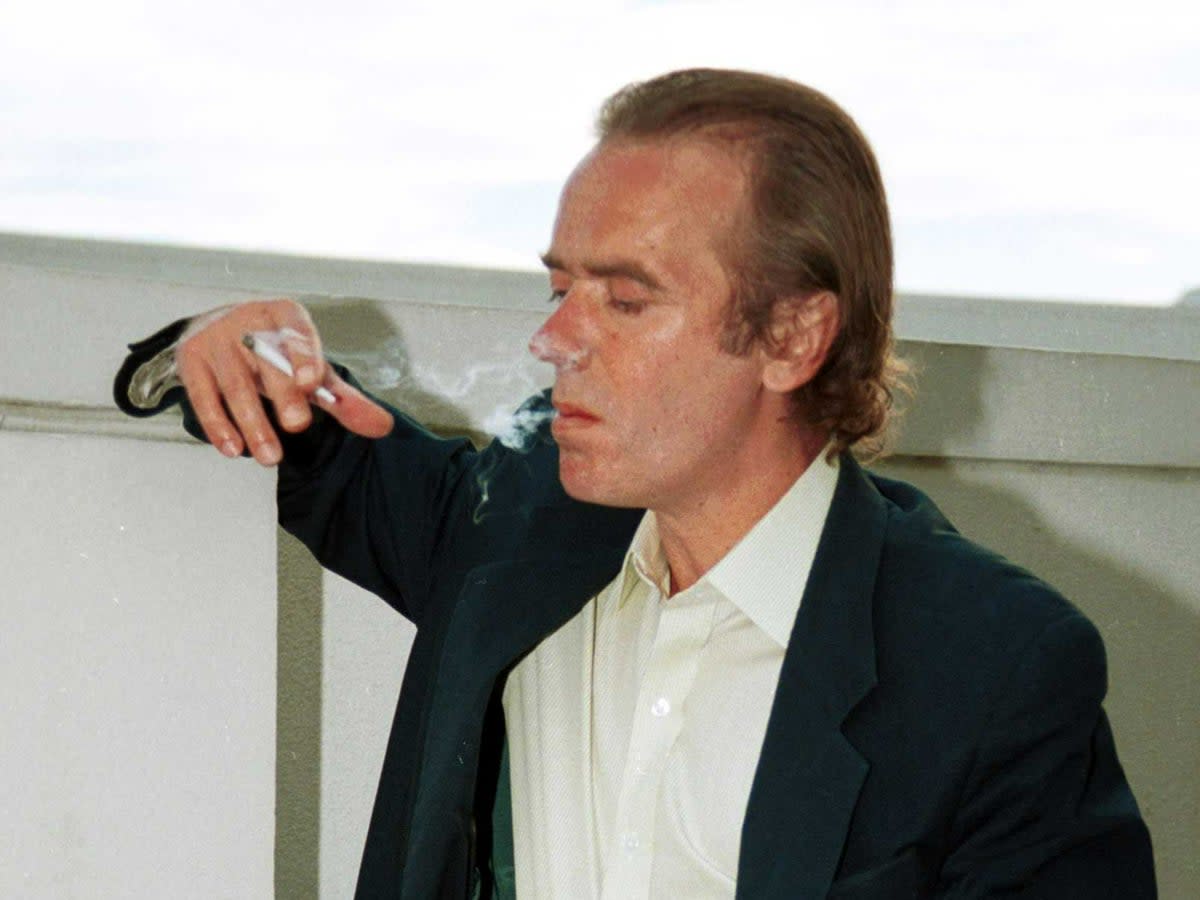

Martin Amis, literary ‘enfant terrible’, dies aged 73

Martin Amis, the “literary agitator” behind acclaimed novels including London Fields, Money and The Information, has died aged 73.

The news of his death was announced by his wife, the writer Isabel Fonseca, who said he had been battling cancer of the oesophagus, according to The New York Times.

Born in Swansea, Wales, the son of celebrated author Kingsley Amis and Hilary Bardwell, he was the author of 15 novels, two story collections and seven non-fiction works that included his memoir Experience, released in 2000. His 1984 novel Money: A Suicide Note, which satirised the excess witnessed in Thatcher’s Britain, was praised as an “era-defining” work whose main character, John Self, was a memorable junk food-eating, chainsmoking, pill-popping monster of a man.

After graduating from Exeter College, Oxford, Amis worked at The Times Literary Supplement before becoming literary editor at the New Statesmen, aged 27, where he met The Observer feature writer Christopher Hitchens. The pair became best friends and remained so, despite frequent (and often public) sparring over their opposing personal and political views, until Hitchens’ death in 2011.

An enfant terrible of the literary world, Amis regularly divided opinion with his work, as well as his personal views, drawing accusations of misogyny along with criticism over his stance on the war in Iraq and views on Islam post-9/11. His male characters were frequently presented as sex-obsessed rogues yearning for success by any means, while recurring themes in his novels included a particularly dark sense of humour. His 1989 novel London Fields was controversially omitted from that year’s Booker Prize shortlist after two female panel members objected to the treatment of his women characters.

“It was an incredible row,” Booker Prize director Martyn Goff told The Independent in 1997. “Maggie [Gee] and Helen [McNeil] felt that Amis treated women appallingly in the book. That is not to say they thought books which treated women badly couldn’t be good, they simply felt that the author should make it clear he didn’t favour or bless that sort of treatment. Really, there were only two of them and they should have been outnumbered as the other three were in agreement, but such was the sheer force of their argument and passion that they won. David [Lodge, chair of judges] has told me he regrets it to this day, he feels he failed somehow by not saying, `It’s two against three, Martin’s on the list’.”

Yet in an interview with The Independent in 2009, Amis described himself as a “gynocrat” who wished the world was run by women. “I was quoted by, I’m pleased to say, Germaine Greer, as saying that all men should be locked up until they’re 28,” he recalled, while discussing his novel The Pregnant Widow. “Boot camp. That would knock some sense into them. We’re terrible. We can’t help it!”

For her part, Greer admitted she struggled to work up any enthusiasm for Amis’s writing. “I read the early novels,” she told The Independent that same year. “He was outstanding. Then I was a friend of his. I’m not a friend anymore, our paths have diverged.

“I don’t think he’s any more misogynist than the average Englishman. Martin is a small man and not quite perfectly formed. He had a polished routine of seduction, but that’s very ordinary. The only thing that’s not ordinary about Martin is that he’s a writer – and he could have been a very good one. He might still be a very good one. We thought he was going to be brilliant when he wrote The Rachel Papers and then Success.

“But then it all went a bit wrong. There was magical realism, restless surface glitter in the prose. It became exhausting and tedious and irritating. It’s very hard to watch clever boys showing off because all the time there’s a different kind of writer, writing perfect stories.”

Few other authors succeeded so thoroughly in dividing public opinion. Romance novelist Jilly Cooper believed Amis wrote with “passion and tenderness” (she also thought him a “charming and attractive man”), while biographer Claire Tomalin called him one of the greatest prose writers of his generation. “I always thought Martin Amis was a bit of a wannabe,” broadcaster and writer Bidisha said. “A dude in the body of a dud. Desperate for the kind of nocturnal, street-side cool which comprehends the nastier impulses and baser instincts of people’s psyches. Emotional r****ds, physical troglodytes, fakes, failures, also-rans: they cram the pages of Amis’s novels. But ultimately, there’s no deep psychology operating behind the work, only a kind of neurotic, infantile fascination with emotional, sexual and physical gore. Martin Amis will never be as gay, Black, depressed, horny or nuts as he wants to be.”

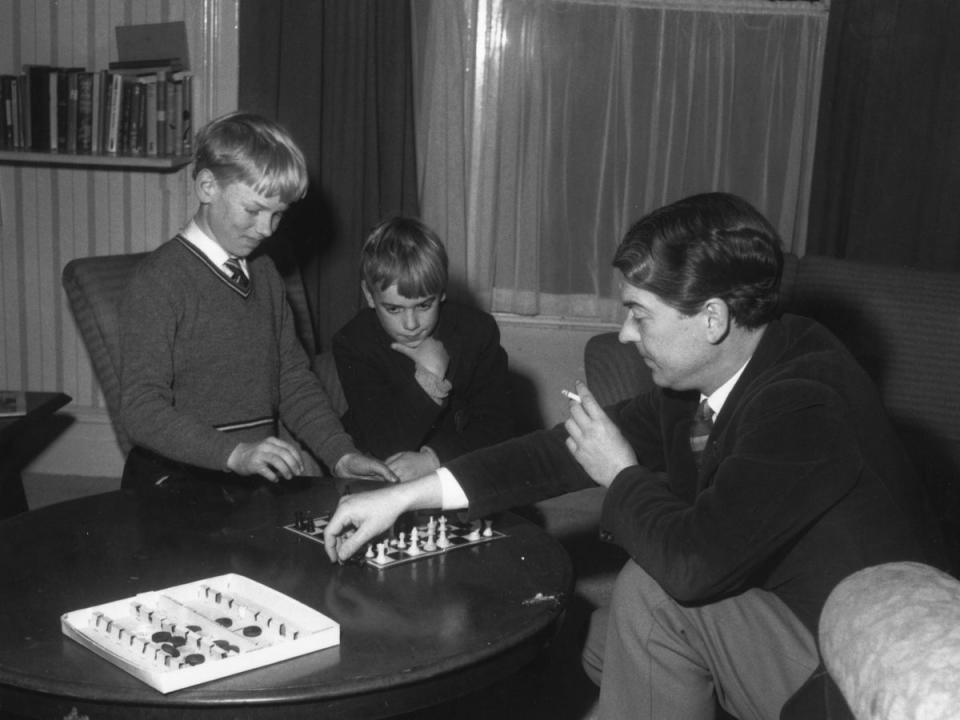

Amis’s family was “very poor” when he was born, but their circumstances improved after the publication of his father’s debut novel, Lucky Jim, in 1954, the success of which prompted the family to move to Princeton, New Jersey, where Kingsley Amis was a lecturer. By the time he reached his mid-teens, Amis Jr was “obsessed” with class and an ambition to rise above what he called his “lower middle-class origins”. Yet he was also derisive of his father’s attempts to do the same, mocking him for early interviews in which he talked in “that lah-di-dah way, hoity-toity, giving himself airs.”

It was Amis’s stepmother, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, who coaxed him away from his love of comic books and into a love of Jane Austen. In an interview with The Guardian at the Perth Festival in 2014, he recalled how he had grown “alienated” and “adrift” following the disintegration of his parents’ marriage. “Jane got me going on literature,” he said. “She gave me a reading list and began leerily with Pride and Prejudice and, after an hour, I went and knocked on her study door and said: ‘I’ve got to know: does Elizabeth marry Darcy?’ I expected her to say: ‘Well, you’ll have to finish it to find out’ but she said, perfectly imitating an aristocratic swoon: ‘Yes!’“

When Howard and Kingsley Amis’s marriage ended in 1983, he stopped reading his stepmother’s work “out of spite, because it was so disruptive when she dumped my father. His three children had to rotate to look after him”. Yet they managed to stay close until Howard’s death in 2014, even if Amis admitted to The Guardian that he felt some guilt about not offering her more praise.

“One of the perks of being the son of a writer is not that you come automatically equipped to write novels, it’s that you don’t bother much about praise,” he said. “Kingsley never bothered much about praise and dispraise. My stepmother did care. She was desperate for praise, and very much wanted it from me.”

Having a famous novelist as a father, Amis was what many would now describe as a “nepo baby”. His father’s success was both a blessing and a curse in his own career, he said, acknowledging the “slight boost” it gave to his profile when he first started out. “Then the culture changed: it became a curse. It was tainted by heredity – by inherited elitism. And so it became accepted that you could say whatever you f***ing well liked about me because, so to speak, I didn’t earn it.”

Despite this, Amis described his personal relationship with his father as “terrific … [my friend] Christopher Hitchens said it was the best father-son relationship he’d ever seen,” he told Esquire. He seemed to credit his father’s liberal – to put it mildly – attitude towards sex as the reason for this: “Any promiscuity excited my father. Though I never saw him being less than courteous to women. And it’s not the case that someone said, ‘Did he make passes at your girlfriends?’ No. I think he fancied one or two of them. But he certainly would not have taken it further than that.

“So the deck was clear for my brother and I to have sex lives unfrowned on by my father or Jane. And it’s different for daughters. But a permission was given, in the broadest sense. And that ensured a very close relationship with him. It was a good father-son relationship.”

Amis himself was married twice, first to Antonia Phillips in 1984, then to American-Uruguayan author and journalist Isabel Foncesca. In a BBC interview, he observed how a move to New York with Foncesca and their two children was interpreted as his saying, “England can go f*** itself”. In the last few years of his life, he and Foncesca lived between downtown Brooklyn and a vacation home on Long Island.

He certainly never shied from criticism of the UK. A 2014 interview with The Independent saw him declare that the monarchy was “nearing the end of the road”, and gripe about the “peculiar atmosphere” that descends in the event of a coronation or jubilee, calling it “entirely irrational but entirely benign”. He admitted that he himself was not immune to the “tribal” pull of football, particularly when England was up against Germany: “A sort of mass hysteria comes over you – I am invaded by the emotions of religion and war. I don’t like it and I can’t watch those matches sometimes. I very much distrust the feelings it awakens in me. I hate the opponents and I love my team and it’s shameful that that’s real.”

Arguably his most controversial writing was on Islam after 9/11. Amis, along with peers including Zadie Smith, Jonathan Franzen, Salman Rushdie and John Updike, grappled with the ramifications of the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. But while Rushdie summarised it as a “dreadful blow” and Smith felt “sick of sound of own voice”, Amis described the collapse of the Twin Towers as the “majestic abjection of that double surrender”.

Five years later, a row was sparked by an interview in which he remarked: “The Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order. What sort of suffering? Not let them travel. Deportation – further down the road. Curtailing of freedoms. Strip-searching people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan... Discriminatory stuff, until it hurts the whole community and they start getting tough with their children...”

In 2007, Amis’s comments resurfaced when his colleague, Professor Terry Eagleton of Manchester University, attacked his argument in a new introduction to his book, Ideology: An Introduction as a means of “hounding and humiliating [Muslims] as a whole [so] they would return home and teach their children to be obedient to the White Man’s law”. He also branded Kingsley Amis as a “racist, anti-Semitic boor, a drinksodden, sel-hating reviler of women, gays and liberals”, adding: “Amis fils has clearly learned more from [his father] than how to turn a shapely phrase.”

Amis acknowledged at Cheltenham Literary Festival that his father was “mildly anti-Semitic” but believed himself to be “pretty free of racism, but I get little impulses, urges and atavisms now and then”.

“I can palpably feel that my children are less racist than I am,” he said. “Their children will be less racist than they are and so it goes on.”

He also defended himself against criticism from The Independent’s then-columnist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, who wrote in October 2007 that Amis was “with the beasts” when it came to his stance on Islam. He argued that her opinion had been “distorted” by Eagleton’s.

“It was a thought experiment or a mood experiment,” he wrote in a letter to Alibhai-Brown, “and the remarks were preceded by the following: ‘There’s a definite urge – don’t you have it? – to say... [etc, etc].’ I felt that urge, for a day or two. My mood, I admit, was bleak – how I longed, Yasmin, for your soothing hand on my brow! It was, in its way, one of the bitterest moments, one of the moments of wormwood, in the strange tale that began five years earlier, in September 2001.”

He later remarked: “The retaliatory ‘urge’ soon evaporated, and I went back to feeling that we must, of course, build all the bridges we can between ourselves and the Muslim majority, which we know to be moderate ... Meanwhile, I don’t want to strip-search you, Yasmin, or do anything else that would trouble or even momentarily surprise your dignity, or that of any other eirenic Muslim.”

Amis’s most recent novel, Inside Story, was published in 2020, and detailed a fictionalised account of the author’s relationship with three men: the poet Philip Larkin, US writer Saul Bellow, and his friend Hitchens. In one of his last interviews, with Esquire, he described Inside Story as “a summation [and] and farewell… I don’t think I’m going to write another novel.”

He is survived by Foncesca and his five children.