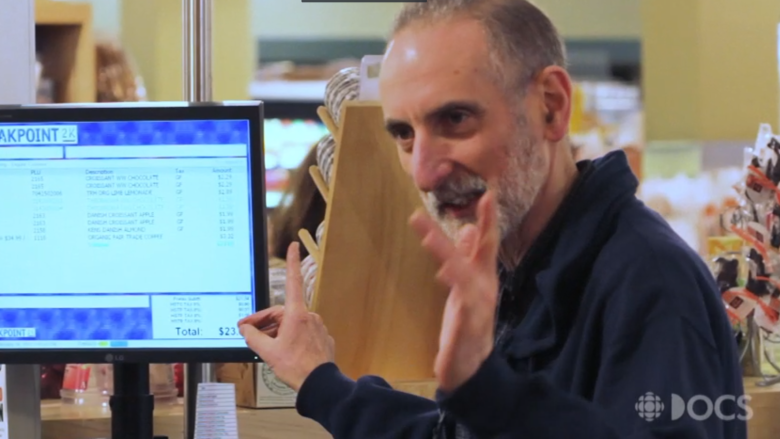

Meet Toronto's genius cashier - a man with a steel trap mind for numbers

For David Teitel, there's magic in numbers.

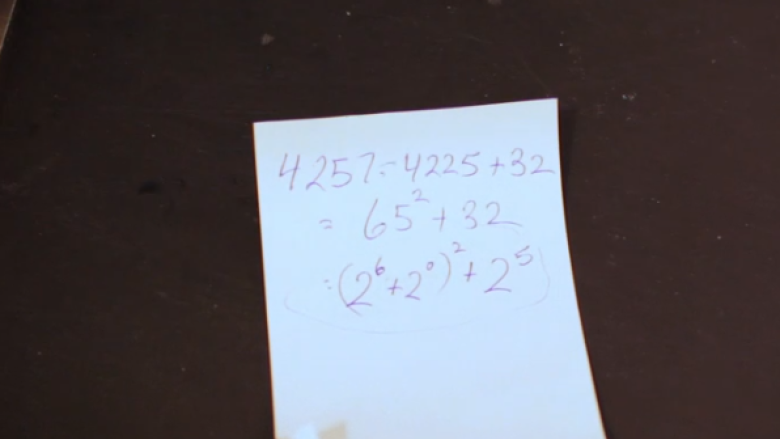

It's the sort of magic most people can't see. But for the cashier who's become a fixture at The Big Carrot health food store on Danforth Avenue in Toronto, the price tags he rings in at the checkout counter evoke historical dates, Guinness World Records and baseball stats — at a ratio of 5:3:2, to be exact.

And he'll tell anyone who will listen.

"The very first time that I correlated a customer's total to a fact just came out of my mouth: 3.43, Don Mattingly's batting average for the 1984 Yankees … I was just relying on the facts that were already in my head."

Teitel calls himself an "idiot savant," for the talent he and his parents first noticed he had when he was four years old.

Never part of the plan

His gift for numbers had both Teitel and his parents believing he was destined for academia — perhaps emerging with a career in architecture.

It was never part of his plan to end up a cashier.

"When I was young I didn't say, 'I'm going to be a cashier when I grow up,'" Teitel recently told CBC Radio's Here and Now, reminiscing on the turns his life took.

Teitel's story was recently the subject of a short documentary, called Numbers Guy, directed by Vanessa Jung.

Teitel was born in 1952, the second of three brothers to parents who had survived the Holocaust. His father had an almost encyclopedic knowledge of geography but was almost always working, the two barely seeing each other.

As a child, Teitel says he was socially awkward.

"I was just doing my homework and getting good marks. I was trying to live up to my mother's image of me as ... the smartest kid on the planet," he says in the documentary.

Ambitions dashed

But as the expectations built, so did the pressure — with Teitel battling mental illness and eventually attempting suicide.

"The worst thing that could happen to me was winning that big scholarship … My parents were holding it over me … 'Your family died in the Holocaust and what, you're going to throw away money?'"

In his 20s, Teitel found himself an architecture-school dropout, living in rooming houses, wandering the streets of Toronto and battling Hepatitis C.

His parents hopes dashed, their relations with Teitel became strained. When he became independent enough, he cut them off.

But the guilt was consuming

"I was caught in a loop of guilt-ridden thoughts… 'Why am I doing this to myself? Why am I so lonely? Why am I so miserable?'"

'Self-image was no longer a mental patient'

In 1977, Teitel finally moved into an apartment he could continue to stay in. Within a few years, he found a job at a health-food store in Kensington Market, with a boss who — like his parents — was also a Holocaust survivor.

At the checkout counter, Teitel came alive — coming out of isolation and connecting with people for what was the first time in many years.

"Over the years, slowly, slowly I developed some social skills — the ability to read customers," he told Here and Now. The biggest challenge there was working out which might be receptive to the facts in his mind and which weren't.

"My self-image was no longer a mental patient," said Teitel, reflecting on the experience in the documentary.

His parents noticed the change too and relations began to mend. Both they and Teitel imagined university was still in the cards for him.

A different kind of success

"When I picked up the pieces I just found myself working in retail and really enjoying it … But eventually I became a veteran cashier."

Teitel's now spent more than 30 years behind the checkout counter and it's a place where he feels comfortable, able to feel most like himself.

In fact, that's where Jung first met him.

"I think I bought something under $20 and he gave me a historical date," she told CBC.

The connection was instant and the two struck up a friendship that left Jung questioning her conventional notions of success.

"I feel like we have this idea of what success is and I feel like David doesn't kind of fit that narrative ... But he did find a kind of success and I think it's just something that the audience is left to think about and think about their own lives and what success means to them."