Mentally ill and isolated: From a rural family home to homeless in St. John's

It was the last night of November 2016, and more than a hundred volunteers and front-line staff hit the streets of St. John's to count every homeless person they could — anyone without a stable roof over their heads.

Jonni-Lynn Caines was one of them.

At 21, Caines was among 38 homeless youths between the ages of 16 and 24 on that cold fall night.

"It was probably one of the scariest moments of my life, because I've never actually been in a place where I didn't know where I was going to go," Caines told CBC News this month.

"The shelters at the time were full. My friends at the time couldn't help me out."

She ended up squeezing into a shelter instead of spending the night on the streets, but said even being there was a frightening experience.

From family home, to homeless

For almost four years, Caines has been living between shelters, friends' couches, and short-term rentals with roommates in St. John's.

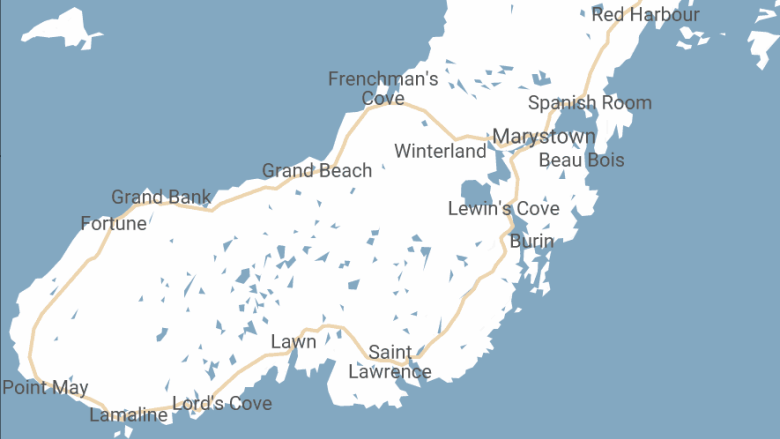

Growing up in Fortune at the edge of the Burin Peninsula on Newfoundland's south coast, she struggled with anxiety and depression for a long time, not knowing what it was.

"It was very stereotypical back home. Mental health wasn't looked at the same as it is now," she said.

So one night in January 2014, Caines talked to her mom about going into St. John's to get help — and made the difficult decision to leave.

The next day, she took a bus to St. John's, spending that night in a shelter. She was 17.

"It was hard for me to get used to a shelter, because I was so connected to my family and I was living at home," she said.

"People at the shelter, they weren't connected to family, they didn't have any supports, they didn't have anything."

At the shelter, Caines met others who were struggling with similar mental health issues.

She also met people with more complex illnesses and addictions — and she was shocked one night when the girl in the bed next to her injected drugs.

Battling addiction

Jonni-Lynn Caines had her own battle with drug addiction. She spent 2015 hooked on opioids. She was 18.

"That was probably one of the roughest times … It was just a cover-up, really. I needed something to get me through the day."

At the time, Caines was dating a guy who had a lot of money and a prescription for Percocet, so they were easily accessible. When she earned money, she immediately spent it on drugs.

Caines credits Choices for Youth with saving her life. But it's tough, especially being a four-hour drive away from her family. With two sisters and two brothers, Jonni-Lynn is in the middle.

"Me and my older sister are really close; we're like best friends. So separation anxiety is kind of crazy," said Caines.

Her family visits, and she knows she can go home to Fortune any time. But she's in a daily program that she relies on.

"I find even just to miss a day right now, it totally throws me off my schedule," she said.

Being thrown off can send her into a crisis.

"My anxiety goes crazy. I get really depressed," she said.

"Sometimes, I don't know that I'm a human. And for me, when that happens, I need to go to the hospital, I need to be brought back to reality."

'So unfortunate': Eastern Health

The agency that provides health care on the Burin Peninsula says Caines could have received some treatment closer to home.

There are seven full-time mental health employees based in Marystown — a psychologist, social workers, nurses, addictions counsellor, and a youth outreach worker — according to Eastern Health.

Staff go to different communities in the area, with a nurse spending one day a week in Grand Bank, near Fortune, and the addictions counsellors visiting every two weeks. Roughly 3,700 people live in the two towns.

"It's so unfortunate that when somebody is looking for help they're not familiar and not aware of the services that exist in their own area," said Kim Grant, regional director of mental health and addictions for Eastern Health.

"That's one thing we're hearing very clearly from the community."

Grant said the health authority is working on getting the message out to clients.

But Caines said the level of care and the difficulty in accessing it — there's no public transit system in the area — could not help her the way Choices for Youth has in St. John's.

A home to call her own

Caines spoke to CBC News one grey May day at Your Turn, Choices for Youth's secondhand boutique, where she works.

Two days later, she moved into her own home for the first time.

The organization set her up in a three-bedroom house that she'll share with two compatible roommates. She can stay until she's 25, and has supports to get used to living alone and to transition out of the program.

On moving day, Caines invited CBC to share in the moment.

Her anxiety was palpable.

"I'm going to be here by myself, and it's going to be my first time out [on my own]," she said.

"There's a lot of anxiety in the air."

She said she's always had someone to tuck her in at night — from her parents to the "amazing" friends she met through shelters and Choices for Youth. Still, she's getting comfortable on her own.

"It's good knowing that [my family] can come and be like, 'Oh this is Jonni-Lynn's house now,' instead of, 'Oh, this is Jonni-Lynn's friend's house.'"

Now that she has a stable home, Caines is planning a stable future. She wants to finish high school and go to university to be a counsellor because "experience is the best teacher."

"I'm excited, but it's definitely going to be something to work for and work on," Caines said.

"I can do it, especially with the supports I have now."