The Militiamen, the Governor, and the Kidnapping That Wasn’t

In these fragile and fractured times, terrible people seek to do terrible things. We reel from one assault to the next, facing down a relentless barrage of devilry and depravity. But—give thanks—sometimes, just in time, the forces of good catch a break. Sometimes those we rely upon to protect us do manage to intervene. Sometimes the terrible people’s most terrible deeds are prevented from ever happening.

That, in general terms, was pretty much the story unveiled on October 8, 2020. As Andrew Birge, U. S. attorney for the Western District of Michigan, declared at that day’s press conference: “All of us standing here today, we want the public to know that federal and state law enforcement are committed to working together to make sure violent extremists never succeed with their plans, particularly when they target our duly elected leaders.” The specifics of the plot in question, recounted in the accompanying criminal complaint and related court filings, were intricate and horrifying, laying out a conspiracy to “unlawfully seize, confine, kidnap, abduct and carry away, and hold for ransom and reward, or otherwise, the Governor of the State of Michigan.” (“Or otherwise”—what awful and chilling chasms of possibility lay left unsaid there?) Copious documents described how, in the spring and summer of 2020, a dark design coalesced among a group of men aligned with various militias and laid out some of the steps subsequently taken as these men prepared for action: conducting daytime and nighttime surveillance on Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer’s vacation home; undergoing focused military training to rehearse for their mission, including drills run through a “shoot house” that served as a mock-up of the governor’s home; testing explosive devices that could be used as antipersonnel devices during the kidnapping; seeking high explosives to bring down a bridge they’d reconnoitered near Whitmer’s home to hinder the expected police response; and so on. When not plotting face-to-face, they would practice meticulous OPSEC (operational security), methodically cloaking their ugly schemings by using code words and encrypted chat apps.

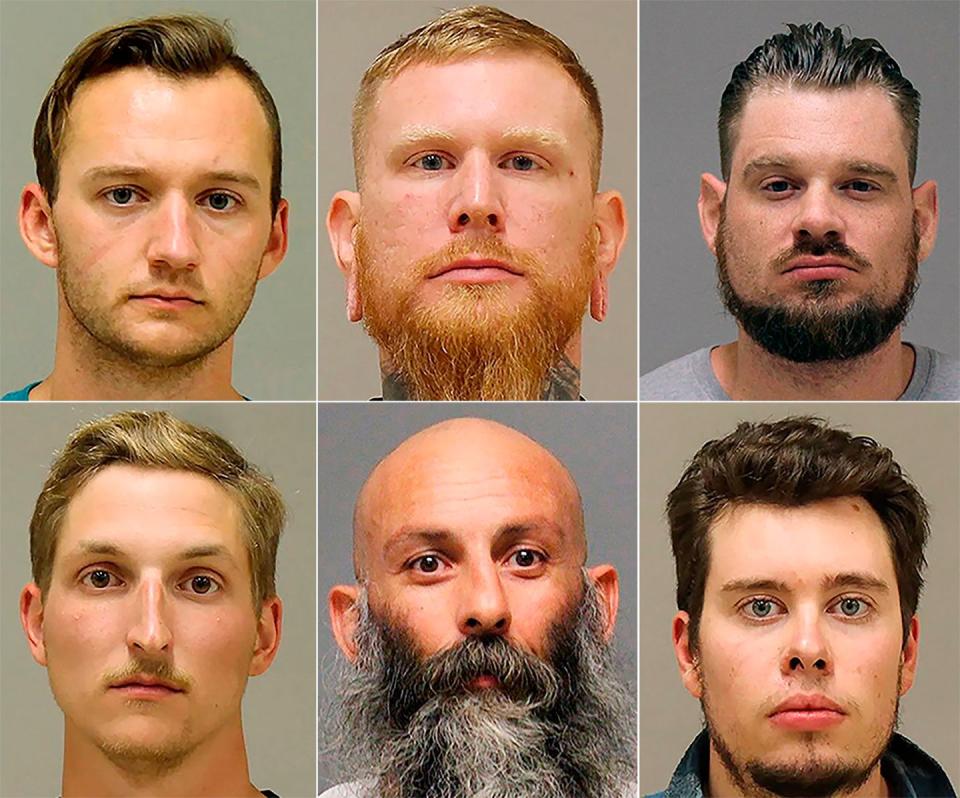

But, mercifully, they were being watched. That’s how, just under a month before the presidential election in a country still reeling from the ideological divides exposed by Covid, on that October day six men came to be charged with the main conspiracy-to-kidnap charge—a potential life sentence—and subsequently with various explosives and weapons charges. “The latest example,” summarized The New York Times,“of anti-government domestic terrorism among far-right extremists.”

Further corroboration, if even required, that these men were just who they seemed to be came when two of the six (Ty Garbin and Kaleb Franks) struck plea bargains, agreeing to plead guilty and testify against their accomplices in hopes of receiving a reduced sentence. Need more? Among the property confiscated from those arrested were at least seventy guns, along with sundry magazines, suppressors, scopes, and silencers; abundant ammunition; and various explosives. Even more? Well, perhaps it’s easiest to get a clear flavor of who the remaining four men (Adam Fox, Barry Croft, Daniel Harris, and Brandon Caserta) were, and of how they thought, and of their intentions, by listening to their own words, recorded while under surveillance.

Fox: “Snatch and grab, man. Grab the fuckin’ governor. Just grab the bitch. Because at that point, we do that, dude—it’s over.”

Caserta: “When the time comes, there will be no need to try and strike fear through presence. The fear will be manifested through bullets.”

Croft: “Wham! A quick, precise grab on that fucking governor. And all you’re going to end up having to possibly take out is her armed guard.”

Harris: “Have one person go to her house. Knock on the door, and when she answers it just cap her . . . at this point. Fuck it.”

Fox: “I want to have the governor hog-tied, laid out on a table, while we all pose around like we just made the world’s biggest goddamn drug bust, bro.”

Caserta: “And I’m telling you what, right now, man, I’m going to make this shit 100 percent clear, dude, if this shit goes down. Okay? If this whole thing starts to happen. I’m telling you what, dude, I’m taking out as many of those motherfuckers as I can. Every single one, dude. Every single one.”

Reading all this, maybe you’re thinking that the only other words you really want to hear are a succinct confirmation that the speakers will all be in prison for a very long time.

That from these particular terrible men, at least, we’re all safe.

May 2022

Brandon Caserta messages me to say that he can’t speak just now. “I’m helping my mom clean behind these shutters of wasp nests right now so I can txt but can’t talk on the phone just yet.” He promises to call soon.

When I initially started digging into the story of these four men a few weeks before their long-delayed trial this past March, my agenda was straightforward. First, I hoped to piece together, in as much detail as possible, the narrative of what they had actually done and said as they careened down such a toxic and alarming path. Second, I wanted to discover all I could about each individual who had somehow ended up in this place. The basic facts of what they had planned appeared well established, but it still seemed that if I could burrow deep enough into the visceral mess of it all, there would be something worthwhile to learn here. There always is. Whether as warning or wisdom or inoculation, we can never understand too much about all the ways in which lives can go wrong.

I found no shortage of material to look at. Even aside from the collected media coverage from the seventeen months between the men’s arrest and the trial, there were an implausible number of court filings—530 of them by the time the trial started, nearly all available to read. In a large number of these, the prosecution and defense lawyers were effectively bickering about what evidence would be allowed to be presented to a jury. There was a staggering volume of material that had been collected by the FBI—one document refers to more than a thousand hours of recordings and “what appears to be over 400,000 direct electronic messages.” While the bulk of this material was inaccessible to the public, protected by court order, one quirk of the legal system is that as the lawyers argued back and forth—typically quoting from the recordings and texts they respectively found most incriminating or most exculpatory—more and more of this material was, incrementally, made public. And so, even though the judge would often rule to exclude from the forthcoming trial what had been quoted, by reading through hundreds of these documents I could submerge myself in the morass.

As I did so, I found myself somewhat taken aback to be contemplating thoughts I hadn’t expected to entertain. For instance, it became increasingly apparent to me that, despite all the surveillance and recording over many months before these men were arrested, the connective tissue of the purported conspiracy seemed perplexingly elusive. By cherry-picking and stitching together disparate statements, incidents, and circumstances, you could certainly fashion an argument that such a conspiracy may have existed—just as the prosecution maintained—but it did seem surprising that the kinds of sustained conversation you might have assumed would be there, in which the principal participants sat around and discussed both the broad scope and the practical minutiae of what they intended to do, didn’t appear to exist.

It was also perplexing to see how much of the connective tissue that did exist involved people who were acting on behalf of the FBI. Take, for instance, what seemed, at first glance, to be one of the more damning events in the alleged narrative of this conspiracy. It is one thing to be told that, on the night of September 12, 2020, Adam Fox and Barry Croft, who according to the prosecutors were the plot’s de facto ringleaders, conducted a nighttime reconnaissance of Whitmer’s Elk Rapids vacation home, driving around the area after first stopping to inspect the underside of the bridge on Highway 31, where they might plant explosives. But it is perhaps another to piece together that the truck in question, a Chevy Silverado, had five people in it. And that Fox and Croft were in the backseat, Croft in the middle, next to a man who turned out to be an FBI informant. And that the truck was being driven by its owner, Dan Chappel, who had been at the center of everything that had or hadn’t been happening for several months. And that he was also an FBI informant. And that next to him up front was another man, whom Chappel had introduced to the group as an explosives expert. And that this man was not an FBI informant. He was an FBI agent.

Not that this strange circumstance—three of the five people in a car at such a crucial moment being affiliated with the FBI—itself absolves the accused men of criminality. The law offers extraordinary leeway for undercover operatives to interpose themselves in such situations in order to expose wrongdoing. But as I learned more about this, and similar scenarios—one defense filing claimed to have identified twelve government informants contributing to this case in one way or another, “assisted by FBI agents working undercover”—it felt as though it cast a more complex and problematic gloss over what was taking place and what it might have meant.

Also, there were times when these different kinds of problems—the curiously prominent role of informants and the strangely disjointed and unexpected nature and tone of the allegedly incriminatory material—seemed to compound each other. Here’s just one example: The prosecution drew attention in the indictment to the fact that the demolish-a-bridge plan apparently emerged shortly after the first daytime reconnaissance trip to the area of Whitmer’s vacation home. “In an encrypted message on or about August 30, 2020, Ty Gerard Garbin suggested taking down a highway bridge near the Governor’s vacation home would hinder a law enforcement response.” So does it make any difference to know that the relevant text exchange between Garbin and the FBI informant Chappel included nine emojis, two Borat GIFs, multiple movie references (one to Monty Python and the Holy Grail), and an “LOL”? Agreed, there is no particular qualifying degree of gravitas required to make evil plans. Flippancy and playfulness are not reliable indications of innocence. But it certainly wasn’t how I’d expected methodical, hate-spewing terrorist extremists hell-bent on destruction would be strategizing, and it made me even more curious to know more.

Daniel Harris was a twenty-four-year-old ex-Marine—ages are as of the March 2022 trial—who had been honorably discharged and received disability benefits. Back in Michigan, he moved into the basement of his parents’ house. He was working locally as a security guard and was looking for a similar job in Afghanistan. In June 2020, Harris had been interviewed by a Michigan news outlet as he took part in a Black Lives Matter protest in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing, telling a reporter, “Everyone’s voice should be heard, no matter the color on your skin. . . . Protesting is important to me because it gives us all a voice to be heard.”

Adam Fox, thirty-eight, lived in the basement of a Grand Rapids vacuum-cleaner business, the Vac Shack, where he sometimes worked behind the counter. To descend into his improvised living space, visitors went through the door with the Building the Best Vacuums of Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow poster on it. He reportedly had two dogs, a black Labrador named Bruno and a white pit-bull mix. Fox liked to get high and had a Twitter feed that, since 2016, had called out perceived foes: Bernie Sanders (“fucking idiot,” “you’re commy ass is a traitor to this country”), Nancy Pelosi (“shut up hag”), Chuck Schumer (“you little bitch”), Barack Obama (“everything you represent is weakness,” “go fuck yourself”), Jimmy Kimmel (“freedom hating commie”), Hillary Clinton (“Shut up traitor”), and, um, Twitter itself (“fuck you Twitter”). Many of the most inflammatory statements netted by the government were Fox’s and, as already noted, painted him as one of the plot’s leaders.

Barry Croft, forty-six, was a long-distance truck driver from Delaware raising three girls, from an earlier relationship, with his partner Chastity Knight. An avid constitutionalist, Croft had a wild graying beard and liked to wear a tricorn hat—“because,” he would explain, “I feel like we’ve forgotten our past and our history.” On the back of Croft’s left hand is a large tattoo depicting a Roman numeral III inside a circle of thirteen stars, the symbol of the militia movement the Three Percenters, whose name pays tribute to the highly dubious claim that only 3 percent of people in the thirteen original colonies rose up against the British. According to the prosecutors, Croft “held himself out as a national leader of the Three Percenters group.” My search for any clear corroboration or visible traces of this role came up cold, though finding disturbing things Croft has said was not hard. Take, say, this Facebook video message from May 2020: “I don’t play part in that stupid-ass political mafia shit that you dumbasses wash your heads in. I don’t do any of that. That’s gay to me. I want to hang all them motherfuckers, all of them. There is not one motherfucker serving in this bullshit government that I don’t want to take, stick to a motherfucking tree, and dangle until they ass tongue hang out their mouth.”

That certainly made him sound like a monstrous, tightly wound ball of hatred, though not everything did. Croft gave an interview for a YouTube channel, The Bradley Bennett Show, in July 2020, before he was incarcerated—when, according to the prosecution, Croft was neck-deep in a secretive and extreme kidnapping conspiracy. In this forum, you find a much politer Croft. “One of the things I do,” he tells Bennett, “is educate people on constitutional awareness, sir.” He also has a peculiar understanding of the etiquette of doing a video interview. Early on—the video lasts an uninterrupted forty-nine minutes—Croft starts moving around his home in Bear, Delaware. Then, without explaining—and never breaking his flow—he leaves the house (wearing his tricorn hat), gets into his car, starts driving, arrives at a local store, orders “two packs of Marlboro Red, box” (giving out his phone number, presumably for some kind of discount program—where’s the OPSEC here?), gets back into his car, and arrives home, carrying on talking all this time.

During this conversation, Croft makes a range of cultural references that I hadn’t anticipated. Laying out his principles of living, he says this: “Don’t just demand that somebody be a good person. You take the initiative to be that good person and I guarantee you it’ll rub off on other people—they’ll rise to be around you. They’ll bring themselves up to be around you. You know, I took that from Biggie Smalls, the rapper. He said, ‘Excellence is my presence, never tense, never hesitant.’ And I thought, well, that’s an awesome place to be. How do you attain that? Superior knowledge, wisdom, experience, a culmination of intelligence. Pour it together: never tense, never hesitant. And guess what—I’m a truck driver, but excellence is my presence. Sir.”

I’m not callow enough to suggest that knowing the lyrics to a nineties rap song absolves anyone of any kind of bigotry, or of anything else. Or that Croft’s genial affect here precludes a wide variety of other beliefs and actions. But if we care to understand him, maybe we’ll need to understand this, too.

The last of the four men facing trial, Brandon Caserta, thirty-three, lived alone in an apartment in the Detroit suburb of Canton and worked as a CNC machinist at a factory called Master Automatic. He was an avowed anarchist—the reflex assumption that these men were all hardcore MAGA cheerleaders, and that this could all be neatly linked to the country’s wider political ructions, took a hit sometime after the arrest when an old clip circulated of Caserta speaking about Trump: “You know, Trump is not your friend, dude. And it amazes me that people actually, like, believe that. When he’s shown over and over and over again that he’s a tyrant. Every single person that works for government is your enemy, dude.”

I found myself particularly intrigued by Caserta. At first glance, he seemed to ooze all the right kinds of guilt. He spouted violent rhetoric about potential vaccine mandates and forced quarantines—“A possibility should be on the table to eliminate some contact tracers. . . . We’re going to create a dynamic where no one wants to be a contact tracer ’cause they might fucking die”—and a video released by the prosecution that had been filmed by Caserta in the early hours of October 7, the day of his arrest, was certainly scary enough. Caserta had just been waylaid by the police for not using his blinker, his second traffic stop in recent weeks. After the first stop, he had been plenty angry, venting immoderately in one of the online encrypted chats: “The end times are approaching for these piece of shit cops. I mean that with every cell in my body.” In this new video, speaking into the camera back in his apartment, the fury overflows further. He explains that he is sick of being robbed and enslaved by the state and that if they come across any of these “gang fucking criminal-ass government thugs” during a recon who don’t leave immediately, “they are going to die . . . because they are the fucking enemy. Period.”

This article appeared in the Oct/Nov 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

If that didn’t give a clear enough indication of who he was, well, maybe you just needed to look at him. When the Detroit Free Press published a story topped by Caserta’s mug shot—a photo in which he stares into the camera, the tattoos snaking up his neck just visible on either side of his orange beard, his long earlobes hanging distended, their inserted tunnels removed by law enforcement—the comment section took it from there: “Are his eyes too close together?” “The eyes are looking at each other.” “Yep, probably inbred.” “Evil little white dudes . . .” “Someone in prison is going to have sex with those ear holes.” “These people always look genetically . . . off.” “Dead eyes.” “Small brain.” “Does anyone else hear banjo music?”

Perhaps the most savage measure of the minuscule level of sympathy, or of even the vaguest open-mindedness to other possibilities, in the air in the days after the arrests is what happened when Caserta’s mother started a “Help Brandon fight for his freedom” GoFundMe page. She declared that “Brandon is one of the most kind, honest and generous people you will meet” and requested the wider world’s support. But why sully yourself by touching the untouchable? Why waste time or money trying to save the unsavable? Where is the kindness in enabling the delusions of a mother who won’t accept the obvious truth of what her terrible son has done? The world responded with $120.

Brandon Caserta calls me from the road, telling me about what it is to no longer be where he has been.

“Like, eating good food and then having silence. Having peace. Being able to be comfortable. In jail, you could never get in a comfortable position. Everything is designed for you to be uncomfortable, mentally and physically. And they keep you uncomfortable mentally by keeping you uncomfortable physically. So having physical comfort. Taking a real shower with real soap. Just really simple stuff like that. Enjoying seeing the sky. And clouds is what was really mesmerizing for me.”

Caserta is driving to Grand Rapids. An errand, you might say. Today he will pick up the guns and other property that the government confiscated when he was arrested.

In a dusty corner of the Internet that seemed to have eluded those writing about the case sits a cache of Brandon Caserta’s YouTube videos, videos someone had archived before they were deleted. There were hours and hours of footage, filmed in the two years before his arrest, and though he looked like the same man in his mug shot and his post-traffic-stop rant, he sounded quite different. Mostly these videos consisted of Caserta talking to the camera, patiently expounding and debating his anarchist beliefs, talking about books he’d read, dilemmas he was thinking through, ideas he was mulling over. In one, arguing against the fetish for imagining that constitutionalism might solve all ills, he bolstered his argument by calling up web pages on a screen behind him of all the countries with a constitution. I didn’t find myself agreeing with too many of his conclusions, but there was often something sincere, open, thoughtful, and curious about the way he talked that took me by surprise. And there was one video—on the face of it, the least relevant one of all—that I couldn’t stop thinking about.

I was already finding plenty of reasons to question my initial prejudices about these men and this case: the lacunae in the legal evidence; the disconcertingly heavy-handed role the FBI seemed to have played; the dissonant signals communicated by the accused men’s actual speech, writing, and actions. But the odd truth is that, for some reason, it was this one Caserta video that most jarred me, that forced me to think again. In it, as Caserta speaks, he circles and backtracks through his apartment, in constant motion, so that you can see some of the markers of his life: an anarchy flag on one wall, the Bill of Rights on the wall opposite, a Gadsden-flag coiled snake with the slogans Don’t Tread on Me and Liberty or Death, the Second Amendment Since 1789 banner. There’s no indication that he’s high or acting out in any way for an audience. He just seems genuinely, sincerely interested in exploring the philosophical paradoxes and recursive loops of logic of the topic suggested by the video’s title, that title being “Contemplating on whether or not I friggen suck.”

This, in full, is what Caserta says:

“You know, I’m kind of just walking around my apartment . . . and I was thinking, how do you really know if you suck? You know what I mean? I mean, I don’t know, like, I got a decent place here. How do I really know, though, if I suck or not? Know what I mean? Like, maybe I do. ’Cause you already know there’s a bunch of people out there who think they’re really sweet, but they actually fucking suck. And you know that. You know that’s true. I guess I could maybe, like, believe that I don’t suck, but what if I actually do? You know? What if I actually suck real fucking hard and I just, like, can’t see it? I just don’t know it, you know? [Laughs.] You ever think about that? Like, what if that’s true, man? Like, what if you’re just a big, fat, sucky loser? You know? How do you really know? How do you really, actually know? You can believe that you don’t fucking suck ass, but what if you do? What if you’ll always suck? You know? How do you really know? What, are you going to ask someone else? ‘Hey, do you think I suck?’ Maybe you’re asking another sucky-assed person if you suck. And they say, ‘Nah, you don’t suck.’ Even though in reality they fucking suck. How do you know? There’s people that think they fucking suck, and they actually don’t suck. At all! Who decides who sucks? [Laughs.] How do you know? I’m trying to figure it out, dude. I think it’s possible that I fucking suck. At least a little bit. You know? I kind of think I suck a little bit. I think it’s gotten better. I don’t know, man. I’m kind of just looking around. I think it’s possible that I might fucking suck a little bit. I think I need to do something about that. Later, guys.”

I’m aware that far meeker, geekier, more likable, and more thoughtful people have proved capable of the most heinous acts. But—and I don’t quite know how to put this without it sounding like some kind of weird and oblique personal confession—in these moments, I somehow felt like I recognized something fundamental about who this guy was. As with his other videos, it wasn’t that I agreed with a lot of what he said, but I did understand the way that he thought. And that threw me. I couldn’t work out how to square the person I believed I saw in this video with the person who appeared in the government narrative of this plot. Maybe that was my failing.

In Brandon Caserta’s memory, it happened like this: One day in October 2020, he went to work and never came home.

Caserta worked the mid-shift, 2:30 P.M. to 12:30 A.M., five days a week. Fifty hours a week, a little more than twenty dollars an hour, making steering columns for Ford trucks. Around 6:20 P.M., he ordered his usual sandwich from Bode’s Corned Beef, a combination of his own devising, “a double bacon cheeseburger with jalapeño, onion, and avocado” that they’d named the Spicy Brando. That Wednesday, just as he was about to go out for his regular Spicy Brando, he was told that the plant manager wanted a quick word. Walking into the room where he expected the manager to be, Caserta was surprised to discover that the lights were out. Then they flipped on and about fifteen plainclothes law-enforcement agents, their faces covered by balaclavas, jumped on him.

“Stop resisting!” they kept yelling. “Stop resisting!”

“I’m not resisting at all,” he pointed out.

At first, he hadn’t a clue who was doing this and was a little relieved—funny, he would wryly observe, in retrospect—when he realized that his captors were working for the government. “I had no idea what was going on,” he says. It was maybe two hours later that he began to understand that he was accused of being part of a conspiracy, one that involved Adam Fox and Barry Croft.

“Are you serious?” he asked.

In the buildup to the trial, there were other developments that seemed more screenplay than reality. In July 2021, Richard Trask, the FBI agent whose account had formed the central narrative of the initial complaint, was arrested, having viciously assaulted his wife after they returned home from a swingers’ party, and subsequently fired. The following month, BuzzFeed’s Ken Bensinger and Jessica Garrison broke the news that a Twitter account describing itself as run by the CEO of a cyber-intelligence firm called Exeintel had, ahead of the Whitmer kidnapping arrests, tweeted coded celebratory tweets about this impending law-enforcement triumph. According to the story, one of the firm’s listed owners was another FBI agent, Jayson Chambers, a man so integral to the investigation that, according to one defense attorney, between March and October 2020 he had allegedly exchanged 3,236 messages with the embedded informant Dan Chappel. These potential FBI misdeeds would be adjudged inadmissible in court, but even if you weren’t minded to believe the most extreme conspiracy theories—that the whole kidnapping plot had been fabricated by people within the FBI, say, to draw attention and business to this private company—it all felt very untoward and disconcerting.

Even so, I found it difficult to imagine that the defendants wouldn’t be found guilty. For one thing, even if the FBI’s immersive role might offend an everyday sense of fairness, I knew that, legally, the bar to using entrapment as a successful defense was generally a high one. Likewise, what was required to establish guilt on the main charge of conspiracy to kidnapping was slighter than you might assume. Whether the plan was confused or impractical, or in all likelihood would never have been carried out, was irrelevant. What was required was that two or more people conspired or agreed to commit the crime of kidnapping, that anyone involved joined knowingly and voluntarily, and that at least one member of the conspiracy committed a single overt act to advance or help the conspiracy. That’s it. The indictment detailed nineteen such acts, and the jury need only be convinced of one.

To prepare for their defense, defendants were provided access in jail to all of the FBI’s surveillance material on laptops. Caserta spent months, up to ten hours a day, listening and reading, trying to understand the case against him. “I wanted to know what was really going on,” he says, “because it didn’t make any sense to me why I got in charged with this.” He knew there was plenty of stuff said in private that sounded bad. “All this rhetoric from us,” he says. “It’s pretty gruesome, I’m not going to lie.” But he maintained that that was all. “I didn’t do anything. I just said mean stuff.” He and his legal team scoured the material nonetheless, searching for any moment when it might seem like he had agreed to be part of this plot. “Looking for this thing, right?” he says. “And it was just never there, dude. It was never there.”

As he thought back, even when he’d been aware of some component of what was now considered this grand plot, it just hadn’t been like that. He remembers, for instance, a moment during a September training weekend in Luther, Michigan, when Adam Fox referred to the idea of a trip to the governor’s house.

“It seemed like a joke to me,” Caserta says. “Like, Oh yeah, you’re going to go look at her house? What, are you going to go and TP her house or something like that? Are you going to go poop in a brown bag and put it on her porch and set it on fire and be like, ‘Screw you, dumb bitch,’ you know what I mean? That’s literally what it seemed like to me.”

In the second week of March 2022, the four defendants were brought to Grand Rapids for the trial. As it began, the two sides started to lay out their positions. The government’s tale was of a terrifying, focused plan: “The Defendants agreed, planned, trained, and were ready to break into a woman’s home where she slept with her family in the middle of the night, and with violence and at gunpoint they would tie her up and take her from that home, and to accomplish that they would shoot, blow up, and kill anybody who got in their way, in their own words, creating a war zone here in Michigan.” Statement after statement, and action after action, over a period of months was portrayed as articulating, propelling, and fulfilling this plan.

The defense’s counterargument reiterated a series of themes. First, that while the accused may have said terrible things, it was all talk. Second, that much of the worst talk that the government presented as relating to this purported conspiracy was often about other things altogether. Third, that despite some of the things said and done, there was never a clear and sustained plan to do what was alleged. Fourth, that insomuch as there was ever even the vaguest semblance of a plan, it was one that was pushed forward at crucial moments by the FBI and its informants.

I don’t want to belittle the substance of some of what the government presented. The worst of the defendants’ statements—some of those I’ve already quoted, as well as very many others—were abominably nasty and callous and threatening, and often gave good reason to wonder and worry whether these words reflected actions that the speaker might take. To actually hear the sound of the words spoken, as the recordings were played out loud in the courtroom, was deeply disturbing.

Aside from anything else, it was clear that the defense would need to undermine the prosecution’s implication that these statements were practical declarations of intent. An early, memorable preview of one way in which this might be done was given in the opening statement of Barry Croft’s attorney, Joshua Blanchard. Croft’s statements were probably, at face value, the most damaging in their full, untrammeled unpleasantness. Proclamations like this: “I’m going to hurt people. I’m going to hurt people real fucking bad. I’m going to burn motherfucking houses down and blow shit up. I’m going to do some of the most nasty, disgusting things that you have ever read about in the history of your life.” If the jury believed that these outbursts bore any definite relation to actual plans, only one verdict seemed likely.

Given that there was no disavowing what Croft had actually said, Blanchard instead argued that his client’s speech should be considered not as a practical road map to future real-world action but as a subset of a rich and wide seam of Barry Croft crazy talk—talk that generally erupted when Croft was, in Blanchard’s vivid non-legalistic phrasing, “absolutely bonkers, out-of-your-mind stoned.”

And then Blanchard offered a colorful list of other outbursts that he knew the authorities had listened to:

“When they heard Mr. Croft was talking about diverting rivers into underground caverns in the Shenandoah Valley so he could grow food by redirecting light using mirrors, they should have known this was stoned crazy talk and not a plan. When their snitch reported back that Mr. Croft was telling him about how the Egyptian pyramids create a counter magnetic flow that would allow a celestial chariot to enter the atmosphere at three times the speed of light without crashing into the earth’s crust, they knew it was crazy stoned talk, not a plan. . . . When the snitches heard that Mr. Croft said, well, what we should do is we should cut down all the trees along the Indiana/Ohio/Michigan border to protect the state . . . because, I don’t know, people can’t step over trees? They knew it was stoned crazy talk and not a plan. . . . When they heard talk about shooting down airships . . . .” And so on—there was quite a bit more of this.

A good argument, maybe. But there was far more to the government’s case than that.

June 2022

I drive to Michigan to meet with Caserta. He has been strangely evasive about where exactly he is staying and texts to suggest that we meet in a tiny park off a road near a lake in the northern outskirts of Detroit. I sit at the single picnic table and wait. There’s no one else around.

According to what I’ve heard in court, I should be worried. Dan Chappel—an Army vet and firearms instructor with an impressive Iraq service record—testified that when he visited Caserta at his apartment, he hadn’t felt safe alone in Caserta’s presence. In fact, Chappel explained how he’d been sufficiently concerned that he always made sure that the door was behind him as they talked, so that, if need be, he could escape. “He just had violence in him,” Chappel said.

Today, Caserta arrives on a bicycle. “Hey,” he says. “What’s up?” When we start talking, the sun is bright. Before we stop, it’s dark. There’s still no one here but us and the evening mosquitoes. At one point he mentions how it’s good to be able to “show people that I’m not this crazy, psychopathic terrorist that they kept saying I was, you know what I mean? I’m just a regular guy, works at a machine shop in Detroit, Michigan. That likes shooting guns, that likes freedom. And yeah, my philosophical beliefs may not be in agreeance with everyone else’s, and I may have opinions that offend people, but, you know, I’m not a bad guy, you know what I mean?”

After a while, I discover what he hadn’t explained about where he was staying. He’s still piecing his life back together, and a few days ago he was invited to move in for a while at the nearby home of a friend’s parents. As the night’s conversation winds toward an end, the dark is broken by the headlights of a car pulling up, and the driver—the person Caserta is staying with—walks over.

“Nice to meet you,” says Caserta’s friend, his fellow defendant Daniel Harris.

The government’s case wasn’t, on the surface, a flimsy one—it was built up over twelve days and featured thirty witnesses. The key points of dispute were often less about what had happened than about what each event meant, and this was never more apparent than in talking about the various militia-training sessions that had taken place. Even though the prosecution tacitly acknowledged that non-incriminatory versions of such events do exist—after all, the ostensible reason informant-to-be Chappel gave for having joined the Michigan militia group known as the Wolverine Watchmen was to keep up with his firearms training—they relentlessly portrayed a series of such training events in the summer of 2020 as specific preparation for this kidnapping plot. In this context, some of what took place—practicing maneuvers in a “shoot house” or “kill house,” say—at first glance sounded pretty bad, especially if, like me, you know next to nothing about gun-training routines. But on closer scrutiny, moments like these often felt less conclusive. For one thing, this kind of training maneuver turns out to be a fairly generic and commonplace one. The testimony suggested that everyone participating at training events took part in these exercises, including participants not implicated in this plot. And there was no persuasive evidence that the defendants had ever obtained details of the layout of any Gretchen Whitmer residence, let alone specifically styled what happened in these shoot houses on such information. It might still be true that the defendants had privately agreed to be practicing particular skills for a particular goal, but from what was presented in court, that seemed far from proven.

At times, so different were the narratives being presented that it felt as though the same evidence seemed equally satisfactory to both prosecution and defense. One example was what might be called the Dorito recording, an audio clip the prosecution considered damning enough to visit twice. Along with the conspiracy-to-kidnap charge, Croft and Harris were charged with possession of an unregistered destructive device, related to their attempts at blowing up improvised explosive devices at two training events, the first time unsuccessfully, the second successfully. The defense view seemed to be that these were nothing but glorified fireworks, being blown up for the reasons anyone blows up fireworks. The prosecution asserted something very different and far more sinister: “These IEDs were meant to use to kill police or security who may be with the governor when they attacked.”

The audio in question had been recorded at a weekend-long training event in Cambria, Wisconsin, in July 2020. As it begins, Croft can be heard being approached by his twelve-year-old daughter, Amber.

Amber: “Daddy!”

Croft: “What, honey?”

Amber: “Do you want a Dorito?”

Croft: “Honey, I’m making explosives. Can you get away from me, please?”

Amber: “Oh, okay.”

Croft: “Yeah, thank you. I love you. Get out of here.”

It felt as though the prosecution imagined that the casual brutality and inhumanity of the whole despicable affair was laid bare right here, in these few naked seconds, for all to hear. And you might see it like that. But maybe you could see it another way. Those at this weekend event emphasized that it was a family occasion. Other people had kids there, too. There was a swimming pool, a barbecue. This might not be everyone’s idea of a great weekend out—it’s certainly not mine—but if you’re unaware that there are people who see great appeal in a family get-together with food, swimming, running around with guns, and maybe a bit of extra fun blowing shit up, without there necessarily being any actively seditious or felonious agenda, then you may wish to consider whose ignorance that reflects.

Hearing this clip, I also wondered whether listening to Croft here might influence the jury in a more intuitive way, one the prosecution didn’t anticipate. The jury had effectively been told that this man was a monster, and they had already been played a series of other recordings in which Croft did a fair job of living up to that billing. But here, if the presence of explosives didn’t make you disregard everything else, as presumably the prosecution hoped or assumed it must, you could hear someone who sounded far less like a monster than like a parent, one who seemed to have a sweet, respectful, and gentle rapport with his daughter, one it wasn’t easy to imagine he was preparing to throw away.

Caserta and I talk at some length about his journey to become the man who would be arrested on October 7, 2020. After what he describes as “a pretty normal childhood”—skateboarding, shooting his BB gun, learning guitar, fantasizing about being a rock star, mountain biking—in his mid-twenties he found himself feeling adrift. His life wasn’t going the way that he wanted it to go. “I felt like kind of like Morpheus says in The Matrix, it was ‘like a splinter in your mind.’ It’s bugging you. You know there’s something wrong with the world and you know something’s going on, but you don’t know what it is. And that’s kind of what I felt. So I started reading a lot more books about philosophy and freedom.”

When Caserta reels off a list of the people whom he subsequently discovered and found useful or influential—David Icke, Alex Jones, Lloyd Pye, Jordan Peterson, Mark Passio, G. Edward Griffin, Ron Paul, Larken Rose, and Lysander Spooner—I flinch more than once. Even so, when Caserta explains what he took from them, it’s hard to see how it differs from a standard liberal we’d-like-the-young-to-think-for-themselves screed. “Things weren’t going my way, and I realized, You know what?” he says. “The problem isn’t the world. The problem isn’t outside. The problem is me. The reason why I’m not getting what I want and what I desire is because of me. So I need to change myself, and then the external world will change for me. If I enact good behaviors into the world, the consequences that I’ll receive will be better, especially if I work hard at it. So I developed that mentality to where the taking on of personal responsibility will generate happiness. I kind of learned that from Jordan Peterson. And I said, You know what? I’m going to try this. And it worked.”

Guns became important to him after the March 2019 mass shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand. To him, the New Zealand government’s subsequent moves to restrict gun ownership made no sense. “I thought to myself, We have a lot of those mass shootings in America, and there’s a lot of people that are in fear,” he says. “So the best thing I can do for myself and for people I care about is to actually get a firearm and really, really learn how to use it in case something like that happened.” He bought a Smith & Wesson SD40 VE, then a Bushmaster XM15-E2S, then a Glock 29. The Glock 29 is what he’s carrying right now—he has a concealed-pistol license. He notes that he’s never shot, or even drawn, a gun in anger.

He had also begun to identify as an anarchist, again inspired by his latest reading, specifically Larken Rose’s The Most Dangerous Superstition and Lysander Spooner’s No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority. “When they were explaining the concepts of authority, that is something that really helped me wake up,” he says. “I realized that the state is an institution of violence and that everything that it does is predicated on the initiation of force. And that’s in violation of the anarchist principle, which is the nonaggression principle. And that’s a huge problem that we have going on today is that everyone thinks that anarchy means chaos and mayhem. So when you say you’re identifying as anarchist, they think that you want people to die.”

In 2020, as the Covid weeks turned into months, Caserta decided he wanted to find people to train with. “Prior to that, I’ve been training on my own, like in my apartment and stuff.” He started researching militias and was soon invited to Wolverine Watchmen training events, though as far as he’s concerned he was never a formal member. “The way I would explain to someone is just like: a group of guys getting together and going out in the woods and shooting guns and just having fun. And that’s how it was the whole time. It was never like this secretive, in-depth, conspiratorial, like, ‘Let’s figure out how we can attack the government.’ It was never like that. They took random conversations out of context, applied their own context to it, and then tried to leave the context out of court and make it to where the defense couldn’t actually put the context into the statements so that the government’s narrative would hold water, essentially. But yeah, it was always like just a friendly camaraderie type of environment where people just had fun and being American and shooting guns in the woods, man.”

Caserta had been prepping for some time before that. “Spending money on storage-able food, water, filtration, ammunition, knives, saws, fire-starting kits, stuff like that. I already had everything pretty much ready in case something bad happened.” One bit of common ground among people he would meet in this world was a sense that you have to prepare for WTSHTF. When the shit hits the fan. Many of the statements that, in court, were taken as references to “when we kidnap the governor” were, says Caserta, references to this more general sense of a coming upheaval. “They think we’re this apocalyptic white-supremacist group of just gun-toting violent extremists that just absolutely hate the government and they want war to happen,” he says. “I’ve never met anyone that legitimately wanted war to happen.” The way Caserta paints it, what they’re readying for is what other people might do. “Pretty much everyone thought, Okay, well, if shit hits the fan, we’re going to defend ourselves.”

According to the government, as 2020 progressed, Caserta’s life was descending into darkness. It didn’t seem that way to him. “I mean, honestly, man, that was one of the best summers I had. I was doing so good. I was getting raises and excelling at my job even more. I mean, I got my car fixed to where I didn’t even have to worry about anything anymore about it. I just signed a new lease on my apartment. I was still hungry for knowledge, still hungry for life. I had multiple dates set up with a couple of different girls, getting back into the dating world again after taking a break for, like, six months. Things were great, man. . . . I mean, I had a blast, and I got to shoot guns and use my gear. And I learned so much skills. Life was going so good.”

Whatever stumbles the prosecution may have made, over these twelve days they were able to show the jury plenty that didn’t sound good. And even though two accused men who had pleaded guilty before the trial, Ty Garbin and Kaleb Franks, were far from perfect prosecution witnesses—they seemed to contradict each other on some details and got others demonstrably wrong—there was a forbidding power to having two men declare that this conspiracy had been real and that they had been part of it, along with the four defendants.

Then it was the defense’s turn. With it, a big surprise. The conventional wisdom was that it would be too risky for defendants in a case like this to testify. But against expectations, Daniel Harris, the youngest of the accused, took the stand.

To begin with, as his attorney, Julia Kelly, led him through a series of questions, it couldn’t have gone much better. Harris came across as kind of quiet and goofy, a politely spoken military kid who carefully explained all the many occasions on which he most definitely did not agree to kidnap the governor of Michigan. But this part isn’t why criminal-case defendants tend not to testify. It’s what comes next.

Harris was cross-examined by one of the prosecutors, Jonathan Roth. For about seven minutes, it went okay. Then Roth referred to the episode that supposedly triggered this whole investigation: the instance when Dan Chappel, having signed up with the Wolverine Watchmen to do some weapons training, was so horrified by what he saw in the group’s private chats that he called a friend in law enforcement, who put him in touch with the FBI.

“You heard testimony,” said Roth, “that Dan Chappel, he is so bothered by the things that are going on in the chats that he immediately calls the police, correct?”

Harris’s reply—it seemed to slip out. It was like he just couldn’t help himself.

“Well, he’s a bitch,” Harris said.

And in that moment, you could feel the air freeze, as though maybe more had changed in the past three seconds than had changed in the previous thirteen days.

You could sense Roth’s got him! excitement, like he knew this was the A Few Good Men moment he’d been dreaming of.

“I’m sorry, what was that?” Roth asked.

“He’s a bitch,” said Harris, quickly, as though if he said the same words fast enough they might somehow cancel out the first time.

“Tell me about that, sir,” demanded Roth.

Seconds ticked by before Harris answered, “Next question.” As if he’d be allowed out of a hole like that so easily.

“Nope,” snapped Roth, the swagger of triumph in his voice. “Tell me about it. Why is Dan Chappel a bitch?”

“I was like, Oh, shit, that’s not good,” Caserta remembers thinking as he watched this unfold. To Harris, on the witness stand, it felt much worse. “It just came out,” Harris tells me. “I’m like, Yeah, there’s two life sentences right there. I’m going away. That is it.” Harris could see how excited Roth was and that the defense lawyers were each clutching their head in their own way, just like, as he saw it, “the see-no-evil, hear-no-evil, speak-no-evil monkeys.” Later, he heard that one of the defense attorneys had received a two-word text from his wife, who had been listening to the trial’s live phone feed: “Oh fuck.”

On the stand, Harris still needed to answer Roth’s question. Again and again, he tried backing away from it, but Roth wasn’t going to let that happen. “Sir, you just told me that he is a bitch for being scared of these memes,” Roth pressed. “Tell me what was going on with these memes that he shouldn’t be afraid of them.”

Dan Chappel was someone Harris had trusted. Someone he had looked up to. Chappel had more military experience than anyone else around, had helped lead the Wolverine Watchmen’s weapons training, had shown Harris and others a video one of his buddies had filmed of operations in Iraq, had seen combat and been injured there, and had talked about being part of a quick-reaction force that had once saved Chris “American Sniper” Kyle. At times, Harris had called Chappel “Dad.” (Sometimes, because they were both Daniels but Chappel was both more senior and larger, Harris would also call him “Big Dan.”) But whatever admiration Harris once had for Chappel was long gone. And now he found himself standing here, fighting for his future, trying to explain why he had just blurted out that Chappel was a bitch. He realized that he might as well just tell the truth. He might as well explain to the jury—and he would look right at them as he finally gave his answer—exactly why he had just said what he said.

“You are scared by words,” Harris began, “but yet you say that you saved Chris Kyle? You went to Iraq, came out, right, hurt—but words hurt you? Words scare you? You are a bitch. Words are words.”

The jury began its deliberations; days passed. The defendants, who had been mostly kept apart for the previous seventeen months but were sharing a cell during the trial, sweated it out together, coping as they could. Caserta and Croft preferred to talk things through, trying to keep positive. Harris would read the Bible or the self-help books that his legal team had given him. Fox would just lie there, day and night, his eyes closed. On the fifth day—Caserta’s thirty-fourth birthday—word came that a verdict had been reached.

No one was found guilty. The jury couldn’t agree on the charges against Croft and Fox—a mistrial was declared and the government swiftly announced that it would try the two men again. Harris and Caserta were acquitted of all charges. Both slipped out of the courthouse undetected. Harris went straight home to play with his puppy, Ollie. Caserta ate Popeye’s chicken in a Grand Rapids hotel room, and those around him fetched what he most needed: toothpaste, deodorant, and a change of clothes.

That first time I meet Daniel Harris, after dark in a Michigan park, he is wearing a gray sweatshirt, a gift from his attorney’s brother-in-law the day after the verdict came through.

“I wear this everywhere,” he tells me.

On the front of the sweatshirt are five words, fourteen letters, in block capitals:

BIG DAN IS A BITCH

As much as the trial troubled me, so did the reaction to these verdicts. Out in the world, much of what was being said seemed to fall into two different camps of thoughtlessness, mirroring an all too familiar modern-day ideological divide. On one side—to give the most cartoonish version—the jurors were Trumpian fools who had been hoodwinked into allowing dangerous psychopaths to go unpunished. On the other, it was confidently proclaimed that a jury had stated unequivocally that the FBI had framed four innocent men in a fictitious plot. Neither presumption seemed justified—if the jury had fully embraced the entrapment defense, for instance, there could have been no mistrial—but few people seemed to bother to look at the very real, specific, and messy reasons why the jury could have sensibly come to the verdict it did.

Anyway, a jury’s verdict is a judgment on what can or cannot be proved, not a definitive pronouncement on what actually happened. So what did? Might it be that at least some of these men really did intend to do precisely what they were accused of doing, even if, despite the FBI’s labors, the assembled evidence remained frustratingly scattershot and tenuous? I suppose so.

Or, conversely, could it really be true that the FBI did, in fact, plan all this, fashioning what some commentators enjoyed calling a “fednapping” conspiracy out of thin air for its own purposes? We live in an era when people often seem only too eager to believe in such duplicitous machinations, but for what it’s worth, my own prejudices run against that. My default belief when faced with a choice between dastardly master plan and accidental shit show is that the latter is far more likely. What if the FBI truly believed it saw the seeds of something scary and dangerous and this belief then became—as beliefs sometimes may—a runaway train? Even setting aside my resistance to accepting that those who are supposed to work for us routinely work against us, one persuasive argument against the FBI having consciously engineered any of this is that, if it did, it made a pretty poor job of it. If it had really agreed to cross that moral line, surely it would have been simple enough to have concocted much clearer and much better evidence—evidence that would have been undeniable.

And there’s another possibility, one that sits in a messier middle ground—the stuff that we don’t much talk about and that the legal system is perhaps ill-equipped to judge, one that hovers in a real world where people think and say all kinds of immoderate blabber to each other without ever being sure how much of it they mean or what exactly is meant or understood by those they are talking to. In actual lives, how thin and ill-defined is the line that separates bluff, playacting, verbal entertainment, and braggadocio from those things that, if the right circumstances fell into place and the wrong kind of momentum gathered pace, someone could easily enough find themselves doing?

Does the truth of what was or wasn’t exist somewhere in that murky in-between?

Whatever the precise reality, it disturbs me how readily those who consider themselves in the mainstream presumed to know exactly what this was. We’re living through an epidemic of certainty, one not confined to the extremes. Sometimes, hearing what happened during both the investigation and the prosecution, it felt as though men who looked like this and spoke like this, who expressed fierce disaffection with the government, who believed in military training and advocated for gun rights, who talked about preparing for some future time when the shit hits the fan, were considered, by definition, already almost, say, 80 percent guilty of some serious crime. It’s one thing to be baffled or affronted or alienated or appalled by the beliefs or choices or lifestyles of others. But, as ever, anytime a society starts acting as though a subset of the population who acts or thinks differently in a way that might puzzle or unsettle others is, de facto, guilty of something, that sounds to me like a society in trouble. Sometimes it’s those who most fear a confrontation who create it.

Brandon Caserta and I sit talking, back at the same picnic table. I think one could have these kinds of measured, thoughtful conversations with Caserta for days, ones in which he’ll debate and acknowledge all manner of nuance—he’ll detail the parts of government that he considers valuable, for instance, and acknowledges the irony that the same legal system that he feels framed him also, in the end, set him free. But he’s not some kind of cuddly, sensitive savant. What I see on his social media I often find deeply troubling, and while he has a very carefully thought-out moral universe that doesn’t seek conflict, he’s ardently clear that there are possible scenarios in which, if sufficiently provoked by authorities he considers illegitimate, he would feel duty bound to respond with force.

Today, as we talk, the sun overhead is blazing. I fashion a shade from a cardboard folder because I know that otherwise my phone, recording our conversation, will soon overheat and switch off. But the wind keeps blowing the folder away. I need something heavier to hold it down. Helpfully, Caserta produces the extra magazine for his Glock 29, which he carefully lays over one edge of the cardboard, keeping everything in place.

In August, the second Barry Croft and Adam Fox trial took place in the same Grand Rapids courtroom. Neither Caserta nor Harris had really gotten to know Croft before they shared a cell for the earlier trial. “Barry is definitely a character, man,” says Caserta. “He gets riled up and he likes to talk a lot. But he’s not a terrorist. He’s not a dangerous person.” They knew Fox a little better and didn’t much like him—“that guy aggravated the crap out of me,” Caserta says—but having listened to and read all the interactions between Fox, Chappel, and other informants and FBI agents, they considered him a victim. “All those people were in his head,” says Caserta, “just pouring gasoline on the fire and getting him riled up and manipulating him and confusing him and making him feel that bad ideas are good ideas. You know, they propped him up to make him feel like he was actually a leader, like he was in control.”

For this second trial, both sides, predictably, had honed their cases. The defense relentlessly highlighted the logical gaps in the prosecution’s evidence and narrative, and hammered away at all the ways in which those associated with the FBI had played a role. The prosecution repeatedly argued that the earliest inflammatory statements from the defendants showed that a plot to kidnap Whitmer predated any FBI involvement; the defense maintained that these statements meant no such thing.

This time, by all accounts, the jury deliberated for just eight hours over two days: Croft and Fox guilty on all charges.

Caserta saw it as the system reasserting itself. “If you say anything wrong about the government or criticize the government in any way, they will spend millions of dollars to come after you and put you in a cage. And if they can’t get a conviction, they’ll retry you again and again and again until they get your body and your soul in a cage.” Outside the court, asked about appeals and other options, Fox’s attorney Christopher Gibbons declared, “We will be pursuing all avenues . . . vigorously”; they subsequently moved for a new trial. Meanwhile, the Department of Justice put out a press release in which Andrew Birge said, in words that seemed to balance triumph and relief, “Today’s verdict confirms this plot was very real and very dangerous.” The tone of much of the media coverage suggested that sanity and stability had belatedly prevailed.

That’s not how I felt. I can’t tell you with any confidence that none of these men would ever have done anything terrible. I can’t tell you with any confidence that, allowed the chance, none of them ever would. But neither can I tell you that I’m comfortable with any sense that an authentic and terrible threat has been satisfactorily and appropriately dealt with, its damage finally contained. What I can tell you is that, as our world evolves in ways that unnerve us, we might thank ourselves to be as careful as we can, every one of us, not to act as though we know for sure what we may not know in the least. And I can tell you this: If everything you knew about these men is what you heard on October 8, 2020, you knew almost nothing at all.

You Might Also Like