The Mississippi River is an iconic part of America. Why doesn't it get more love?

NEAR READS LANDING, Minnesota – At the edge of the Mississippi River, eight kayaks floated in an orderly row.

The group of paddlers had spent the last hour meandering the languid channels that connect the Chippewa River to the Mississippi, spotting flowers that popped with color on the gray September day and watching eagles swoop overhead. Now, they needed to cross the river’s main channel.

Michael Anderson, the owner of Broken Paddle Guiding Co., in Wabasha, Minnesota, parked his kayak at one end of the row. At the other end was his fellow guide, Isabel McNally, who instructed the kayakers to cross together and move fast, lest they come upon a boat or barge.

Then they were off, navigating the stronger current until they reached calmer waters on the other side.

Anderson, who founded the professional river guiding company in 2012, said the idea of paddling on the main channel can be daunting for people – which makes it even more rewarding when he sees them enjoying it. His passion is to help people have a positive experience with the river.

That’s crucial, McNally said, because not everyone expects it. She called the river system a “criminally underrated” place to explore, and the people she’s guided come in with preconceived notions. They believe it’s too big and too scary; they fear getting hit by a barge.

“I wish more people thought they had access to it,” she said. “I want this to be for everyone.”

The Mississippi River is a big deal. One of the world’s great rivers, it hosts an abundance of wildlife habitat, provides drinking water for almost 20 million people and carries more than 500 million tons of freight per year, including 60% of all grain exports from the U.S. It also holds an important place in America’s cultural history, from the Indigenous communities that built their lives around it, to the development of the Mississippi Delta blues, to Mark Twain’s classic tale about Huckleberry Finn’s river journey.

As writer Albert Tousley put it in his 1928 book, “Where Goes the River,” an accounting of a canoe trip from the Mississippi’s headwaters to the Gulf of Mexico, “It’s all the best and worst of these United States … it is more American than any other thing.”

But it seems to carry less reverence than other iconic water bodies across the country. It doesn’t adorn car bumpers or keychains like the image of the Great Lakes. People may view it as a working river, not to be played with, or a source of problems. Worse, they might not think too much about it at all.

That attitude has serious consequences. While the Great Lakes have benefited for years from a billion-dollar program to protect and restore their health, legislative efforts to set up a similar program for the Mississippi have stalled. Meanwhile, the environmental challenges the river faces continue to stack up.

River advocates are finding their own ways to help people connect. Anderson said he likes to think his company has been a small part of a change in how the river is perceived.

And he hopes that once people forge a relationship to it, they’ll be able to learn one of the biggest lessons the Mississippi River can teach: that it connects all of us, and what happens in one place has impact downstream.

“I don’t think that’s a bad thing, for us to have a lens beyond the ‘me,’ beyond what is happening to myself in this moment,” Anderson said. “The river is a very literal sense of that.”

People lack a connection to the Mississippi River basin

Jessie Ritter, director of water resources and coastal policy for the National Wildlife Federation, said the organization’s staff recently conducted more than 70 interviews with people living along the river, including landowners, faith leaders, state agency personnel, nonprofit groups and tribal representatives.

One of their most common findings, Ritter said, was that people don’t feel a particularly strong connection to the Mississippi.

She wasn’t surprised, and believes that the way the river has been engineered plays a role in the disconnect. Many people who live along the Mississippi, for example, see a levee, not the river itself.

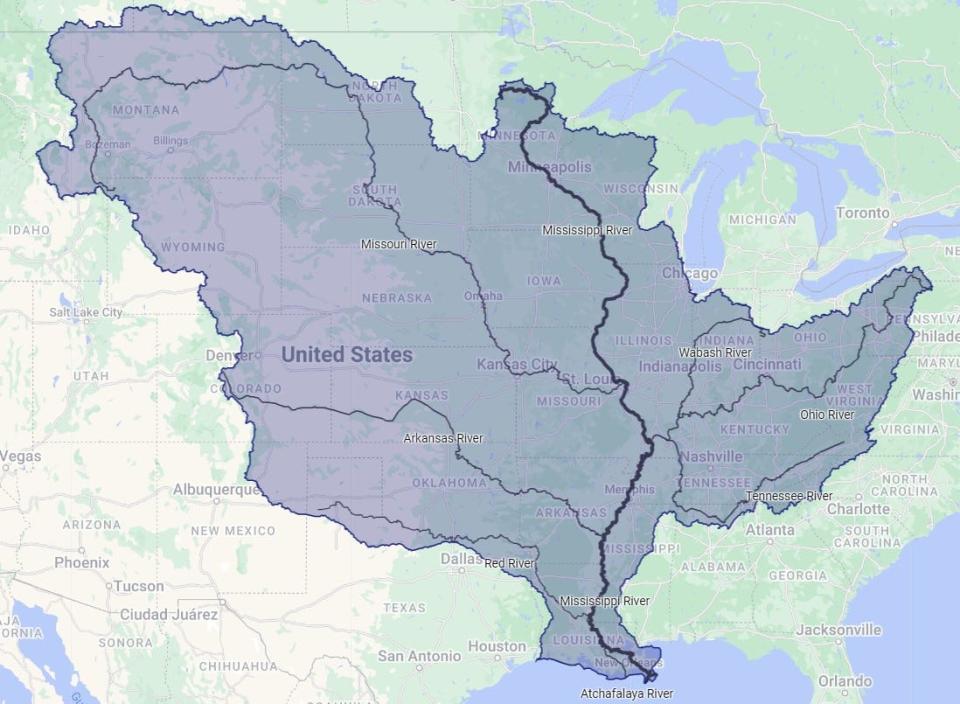

The idea of living in the Mississippi River basin is even more amorphous. All of the rain and snow that falls over a large chunk of the middle U.S. ends up in the Mississippi River, which means activities on that land – like farming and industry – affect the health of the river. But many people don’t realize it.

In Wisconsin, for example, the majority of the state is part of the river basin, not the Great Lakes basin, though the sentimental tie seems stronger to the lakes.

A landmark study out of the Missouri School of Journalism asked respondents in the 10 states that border the river how they felt about living in the river basin. While about half said it was important or very important that their state was a part of the basin, others expressed apathy or loose personal connections. About 15% said they never think about belonging to the basin.

Assistant Professor Kate Rose, the lead author on the study, said the results confirm how much people need to be educated about their place in the basin and the impact of what happens downstream.

“If you don’t understand how water in this area can flow into (another) area, it’s a lot harder to make the case for this,” Rose said.

'It’s very hard to have a love affair with the Mississippi River'

Ritter’s theory – that decades of river manipulation have disconnected people from it – looms large near the mouth of the Mississippi.

Between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, oil, gas and chemical plants line the river, an area that environmental advocates call Cancer Alley because of the increased risks of the disease posed by toxic air pollution. And the Port of New Orleans is a bustling transportation hub, connecting cargo from the U.S. to the rest of the world and vice versa.

More: As Mississippi River swings between historic highs and lows, shipping industry struggles to adapt

All this makes the river unsuitable for swimming and more difficult for recreational enjoyment.

In the mind of Louisianans, it’s a working river, not a sacred place, said Oliver Houck, a law professor at Tulane University. He believes environmental consciousness takes second place to industry, and that because of how it’s been engineered, the river is viewed as dangerous.

“I think it’s very hard to have a love affair with the Mississippi River,” Houck said.

While industry doesn’t hug the shores as much further upriver, there are other changes that may have affected people’s relationship with it.

Decades ago, the Mississippi played an intimate role in people’s livelihoods. When commercial fishing on the upper river was at its peak in the mid-1960s, the industry produced more than 6,000 tons of fish and generated about $9 million, according to a 2018 study in Fisheries Magazine.

Today, just a few commercial fishers are left. Mike Valley, who smokes and sells his catches at Valley Fish and Cheese in Prairie du Chien, is one of them.

Valley has seen many changes on the river but perceives a big shift in what it’s used for. He thinks the current focus is on entertainment, such as fishing tournaments, which he views as taking more than they give back.

“When I was a kid, you could take 50 kids from the ages of 12 to 15 and out of those 50 kids, 45 of them could clean any fish out of the river … and prepare it for the table,” Valley said. Today, he bet, there wouldn’t be more than two.

Even when recreation is drummed up, the river lays claim to a small portion of it. In Minnesota, Anderson said, state tourism points people to the woods and the lakes, particularly the North Shore on the edge of Lake Superior.

The Mississippi lacks protections of Great Lakes, other waters

Anderson said he senses a deeper, more psychological divide — lakes are enclosed and may feel safe to people, while rivers are ever-changing and sometimes flood.

Down in New Orleans, Houck was involved in many cases aiming to prevent environmental abuse of Lake Pontchartrain when he first moved to the city in the 1980s.

“The place we loved enough to save was Lake Pontchartrain,” he said.

Americans have loved plenty of water bodies enough to save them. In some cases, that’s meant forming massive restoration programs with bipartisan buy-in. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, which launched in 2010, is widely recognized as a success story, having funded more than 6,500 projects to clean up the lakes. Republicans and Democrats alike have voted to increase funding for the initiative nearly every year since it passed.

The Chesapeake Bay Program has done the same on the East Coast since 1983, similar to the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan in Florida, which was authorized in 2000.

The Mississippi lacks such a program, and recent efforts to create one have lost momentum in Congress.

“There’s growing recognition that this (Mississippi River) system is not receiving the comprehensive attention that we have for some of our other iconic waterways,” Ritter said. “I definitely think that is a gap, given its size and significance … that we don’t have something from the headwaters to the Gulf.”

John Anfinson, a Mississippi River environmental historian, said that’s had a particular impact on threats to the river. For example, while entities are willing to spend billions to keep invasive carp out of the Great Lakes, he said, it’s been more difficult to find the funds to keep destructive fish species out of the Mississippi.

Here's one place where the river is worshiped

But models exist for getting people to care about and connect to the river again. There are places where it’s almost hard to imagine that not everything revolves around the Mississippi.

One of those places is what’s known as Pool 9 of the upper river, where it forms the border between northeastern Iowa and southwestern Wisconsin. There, the river cuts through the Driftless region, home to a unique topography of towering bluffs.

Larry Quamme, who lives on a bluff in Ferryville, Wisconsin, said that in his part of the world, it’s a banner time for “worship of the Mississippi River.”

“We don’t hear too much about the Great Lakes,” he said. “Everything is about the Big River.”

In 2006, Quamme was among the founding members of Friends of Pool 9, a group of area residents who wanted to protect the natural resources in the area. Today, it has more than 800 members.

In recent years, they’ve teamed up with area schools to offer Mississippi River “adventure days,” where students visit the river and learn how to protect it. They also get a kayak lesson and get to paddle the backwaters – an integral part of the day, Quamme said, because some students haven’t had that kind of access to the river before.

Even though access may look different further south, Macon Fry still believes it’s the key to getting people to appreciate the Mississippi and want to enhance it.

Fry is a writer who lives in New Orleans along the batture, the space between the river and the levee that walls it off from the city proper. Though people have questioned his choice of location – including an old girlfriend who told him if he wanted to live like Huck Finn, he’d have to go it alone – he never has.

More: Is pumping Mississippi River water west a drought solution or a pipe dream?

“The attraction was the river, the endless horizon. It’s like having 1,000 acres as my backyard,” he said.

Although not everyone wants to live on the batture, Fry said he’s noticed more New Orleanians recreating on the river’s shores today than at any other point in the four decades he’s called it home.

He’s hopeful that attitudes might return to those of the early American era, when people treated the river as a public space that was integral to their lives.

“If you can’t see it and you can’t occasionally put your toes in it, then how are you going to appreciate it?” he said. To get people to care, “I don’t think you have to do a whole lot else other than creating access.”

Education about downstream impact could make a difference

It’s fair to wonder, of course, if simply seeing the Mississippi River – even on a regular basis – could prompt someone to care enough to take steps to protect it. Some say more education on its history, challenges and opportunities could make people more thoughtful about its future.

That education can start in the classroom. Tammy Drazkowski, who teaches middle school science at a Catholic school in Winona, Minnesota, asked her students a few years back whether they’d ever learned about the Mississippi in elementary school. To her surprise, none had, despite the fact that their city is on the river.

Today, when time allows, she does a unit on it – including going out to connecting streams and measuring the levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in them, two of the Mississippi’s most persistent pollutants. She talks about the sources of those pollutants, and has found that even students who knew a little about the river are surprised at what’s happening where it bottoms out into the Gulf.

“‘The things we do really affect it,’” she said she tells the students. “If they know more about (the river), they’re going to take care of it more.

Maisah Khan, policy director for the Mississippi River Network, said she sees the 15% of respondents to the Missouri School of Journalism study who never thought about the fact that they lived in the Mississippi River basin as a new audience to be reached.

“A lot of the things that we work on … (are) rooted in the idea that we can’t work on river issues piecemeal,” Khan said. “The connection (between upstream and downstream) not being there is an opportunity we have to educate.”

Ritter, with the National Wildlife Federation, believes that education should also involve highlighting nature-based solutions – in other words, helping people see that the river can be an ally instead of something that has to be controlled. That could look like restoring its floodplain to once again provide natural protection against floods, she said, or rebuilding wildlife habitat.

She thinks people are hungry for that type of information. In the interviews her organization conducted with river residents, many of them expressed wanting to feel more connected to it.

What they want, and could have, Ritter said, is “a relationship with the system beyond its importance for economy and commerce – but also something that can be enjoyed and celebrated for all of its different values.”

Madeline Heim is a Report for America corps reporter who writes about environmental issues in the Mississippi River watershed and across Wisconsin. Contact her at 920-996-7266 or mheim@gannett.com.

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an editorially independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in partnership with Report For America and the Society of Environmental Journalists, funded by the Walton Family Foundation.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Mississippi River is part of America's story. But we don't embrace it.