The Mississippi Sound feels like a bathtub. What does that mean for hurricane season?

The heat has forecasters in awe.

The Gulf of Mexico bakes each summer, and the sun always beats down on the shallow shores of the Mississippi Sound.

But this year, scientists say the water is sweltering.

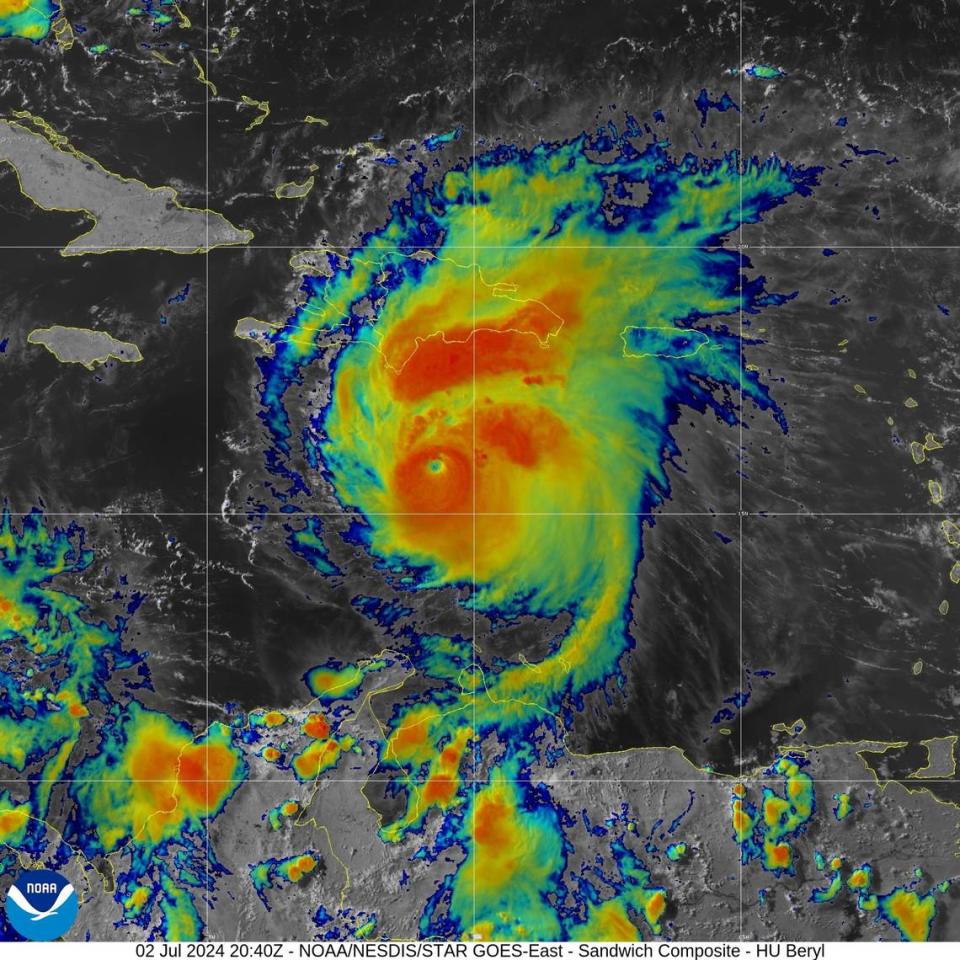

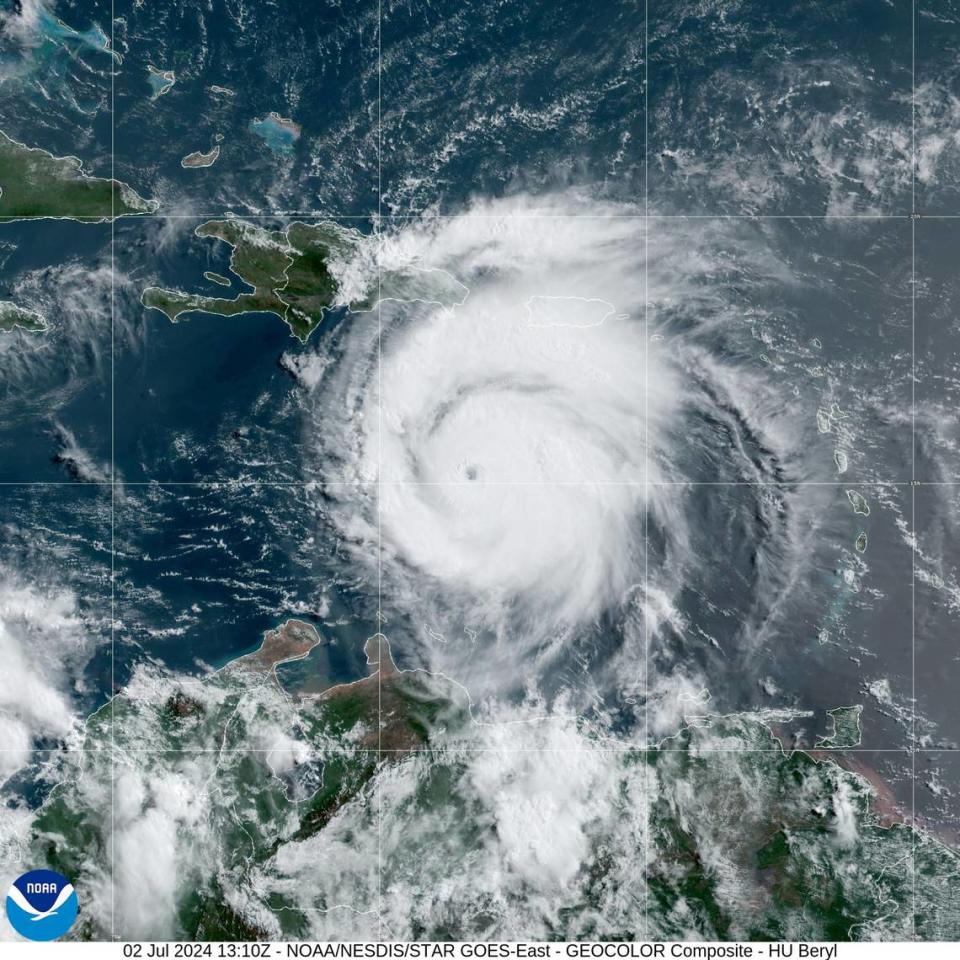

That’s bad news, they warned as Hurricane Beryl and its 160-mph winds stormed through the Caribbean this week, powered by a hot ocean that is red as a flame on most maps of its temperature.

“It’s very concerning,” said Diana Bernstein, an assistant professor at the University of South Mississippi’s School of Ocean Science and Engineering. The heat, she said, is “like bringing more fuel to a fire.”

Warm water is worrying forecasters across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, where a path of warmth fueled Beryl’s rise to becoming the earliest Atlantic Category 5 storm ever on Monday.

The heat has also spread to South Mississippi. A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration temperature gauge at the Bay Waveland Yacht Club measured nearly 90-degree water on Tuesday afternoon. In Pascagoula, at the NOAA Lab, the water was 89 degrees.

The numbers are higher than they normally are even in August.

And they mirror the temperatures in Beryl’s path.

The water near Beryl is so hot, Brian McNoldy, a researcher at the University of Miami wrote on social media, that “if you asked the water in the Caribbean Sea what day it was it would guess September 10.”

#Beryl will spend about 4 days in the Caribbean, beginning midday Monday. If you asked the water in the Caribbean Sea what day it was, it would guess September 10.

You'd think the shock value of this would wear off, but it's becoming MORE shocking!https://t.co/CdrzWVvKiZ pic.twitter.com/TWJTOIs7VI— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) June 29, 2024

How hot oceans fuel hurricanes

McNoldy tracks the heat in a series of graphs, and the lines are all moving up.

Ocean warming is caused by climate change: scientists say seas absorb the world’s heat like a sponge. The temperatures have mostly shocked scientists in an area of the Caribbean and Atlantic where hurricanes often develop, but temperatures have also been above normal since early May in the Gulf.

Forecasters credited Beryl’s development this week to record-hot ocean heat. The warmth helped Beryl become a Category 5 storm more than two weeks earlier than any other Atlantic storm of that category on record, according to Philip Klotzbach, a meteorologist who studies hurricane forecasts at Colorado State University.

One reason why #Hurricane #Beryl intensified to a Category 5 hurricane over two weeks earlier than any other Atlantic Cat. 5 on record is due to extremely high ocean heat content levels. Caribbean ocean heat content today is normally what we get in the middle of September. pic.twitter.com/dmEY7EFrLs

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) July 2, 2024

Warm water adds moisture and energy to hurricanes, said Megan Williams, a forecaster at the National Weather Service New Orleans. The heat from the ocean gets transferred into the storm, she said, helping it grow stronger and faster.

That creates a dangerous event called rapid intensification, when hurricanes approaching the shallow, often warmer waters near land, grow stronger as they barrel rapidly toward a coast.

Forecasters had already warned this hurricane season would be extraordinary, and now they say Beryl is proving it. As the storm churned over a stretch of the Caribbean Sea where temperatures are far hotter than they were 24 years ago, Beryl jumped from a tropical storm to a Category 1 hurricane Saturday afternoon. By Sunday it was a Category 4.

And on Monday, it pounded the Caribbean island of Carriacou and moved west as a Category 5.

Prior warmest May Atlantic Main Development Region (10-20°N, 85-20°W) in the high-resolution SST era (since 1982) was 2010. This animation shows just how much warmer 2024 is than 2010 was at this point. #hurricane pic.twitter.com/kWqGigyTVo

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) May 23, 2024

Where is the hottest water?

The Mississippi Sound is 1.5 degrees warmer than normal, Williams said. That means any hurricane approaching the Coast could gain a last-minute surge in power.

Williams said the Gulf is still cooler than the Caribbean, and the highest Gulf temperatures are off the Texas coast.

The concern is not new — the ocean was the warmest it has ever been last year — but the hot Gulf and Caribbean gained new focus this week because of Beryl’s fast, early and dangerous force.

“Someone needs to remind me what part of the hurricane season we are in,” Jim Cantore, the legendary Weather Channel meteorologist wrote on social media. “I guess these historic warm ocean temperatures are changing the game.”