Missouri banned abortion. But has it prevented any, or just pushed them out of state?

Reality Check is a Star series holding those with power to account and shining a light on their decisions. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at RealityCheck@kcstar.com.

Anti-abortion advocates and lawmakers long championed the prospect of ending abortion in Missouri, but two years after the state’s ban took effect data shows thousands of Missouri women are still getting abortions — just out of state.

Missouri’s near-total abortion ban took effect minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court on June 24, 2022, struck down Roe v. Wade in a case called Dobbs. The state law includes a medical emergency exception but contains no exemptions for rape or incest.

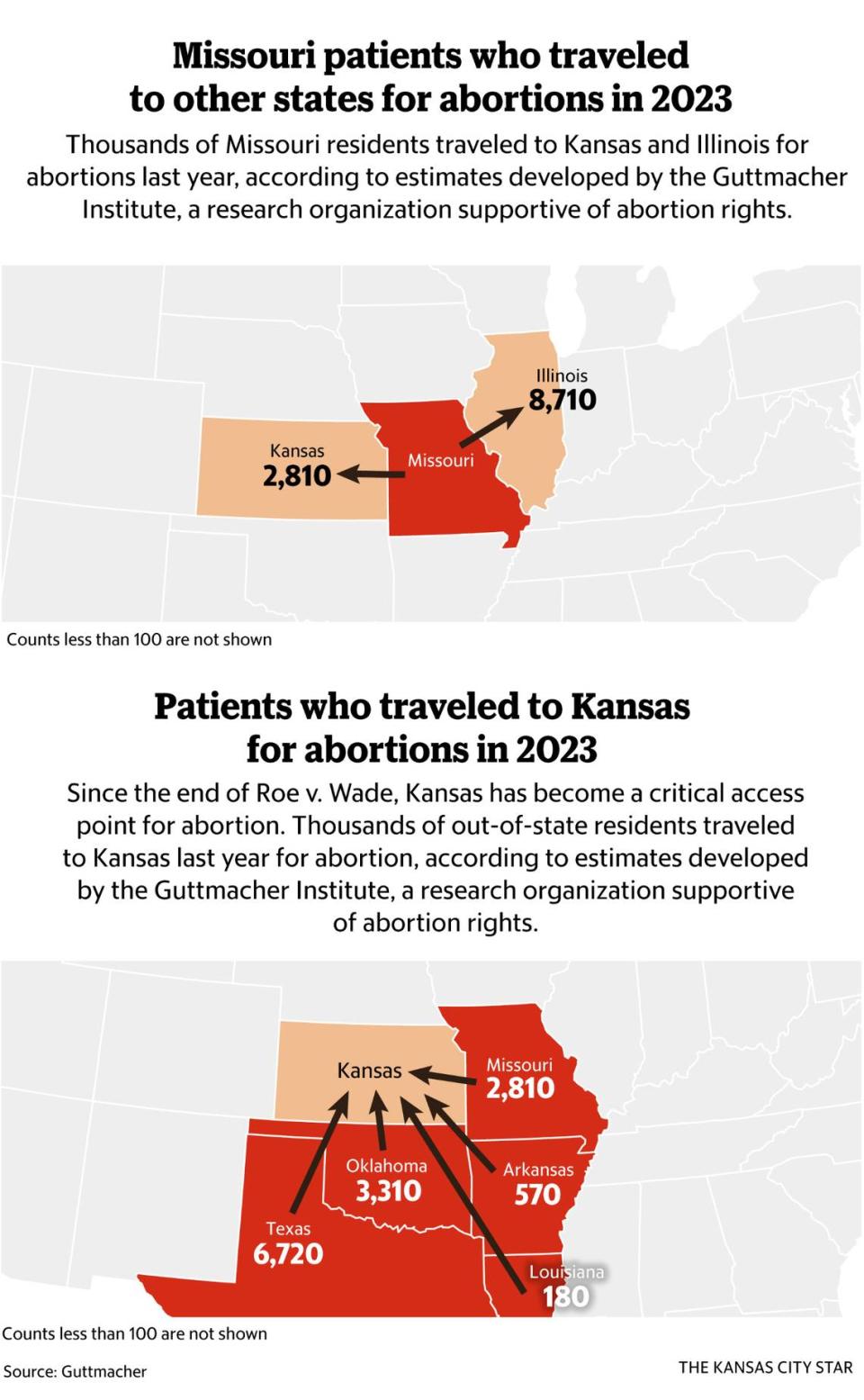

A growing amount of data makes clear that thousands of Missouri women have received abortions in other states, primarily Kansas and Illinois, since the Dobbs decision. At the same time, Missouri residents are now competing for appointments with residents of other states, including Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas, where abortion is also banned.

Even before Dobbs, Missouri residents were crossing state lines for abortion in large numbers. Decades of restrictions passed by the Missouri General Assembly steadily chipped away at access, leaving just one abortion clinic, in St. Louis, operating at the time of the Supreme Court decision.

Anti-abortion lawmakers were so successful in the years leading up to Dobbs that once the ban came, it represented a final blow to abortion access in Missouri rather than a dramatic reduction.

“Missourians had basically been living in a post-Roe reality for a very long time and that the vast majority of Missourians who were accessing clinical abortion care were doing so out of state as far back as 2017,” said Maggie Olivia, senior policy manager at Abortion Action Missouri.

Olivia and other proponents of abortion rights say that reality hasn’t decreased the need for access in the state. Indeed, abortion rights supporters are seeking to restore access through a state constitutional amendment that may go before Missouri voters in November. Election officials are currently verifying initiative petition signatures.

The amendment would enshrine the right to an abortion in the Missouri Constitution, paving the way for abortion clinics to open or reopen in the state. However, rebuilding the state’s clinic infrastructure could take years and Missouri Republicans are also attempting to limit access to a common abortion drug.

Abortion opponents readily acknowledge that the number of Missouri women obtaining abortions out of state hasn’t changed significantly since the ban.

“That has not changed and it’s unfortunate and we’re disappointed in that,” said Samuel Lee, a longtime anti-abortion activist and president of Missouri Stands with Women, the main campaign operation opposing the amendment.

The challenge, Lee said, is “how does the pro-life movement do a better job of reaching out to women who are pregnant, who are considering abortion and saying, ‘You know, we have an alternative and we can help you with an alternative.’”

“That, I think, is still difficult for us as a movement to grasp with. Not from lack of desire, but what is the best way?” Lee said.

Kansas’ critical role in abortion access

For now, Kansas and Illinois play a critical role in providing abortion access to Missouri women. More than 11,500 Missouri residents traveled to the two states in total for abortions in 2023, according to estimates released in June by the Guttmacher Institute, a research organization supportive of abortion rights.

Guttmacher estimates Kansas clinics saw 2,860 Missouri patients, while Illinois saw 8,710. If those estimates prove accurate, it would mean roughly the same number of Missouri residents traveled to Kansas in 2023 as in 2022, according to official state statistics (state of residence data isn’t publicly available in Illinois).

The estimate signals that while Kansas remains a central access point for Missourians, fewer residents are obtaining abortions there following the ban. Before 2022, the number of Missouri residents traveling to Kansas each year routinely exceeded 3,000. Now it sits closer to 2,800.

Providers say clinic appointments that used to go to Missourians are now more often going to residents from other states.

“We used to be able to see a lot of Missourians at the health centers we operate in Kansas,” said Emily Wales, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Great Plains Votes, the organization’s political advocacy operation.

Those Kansas health centers in the past often saw roughly half Kansans and half Missourians, Wales said. Today more patients from elsewhere are competing for the same number of appointments.

Fourteen states have total or near-total bans on abortion. An additional seven states restrict abortion between six and 18 weeks of pregnancy. The states include the entire South, along with the upper Great Plains.

For many residents living in Southern states, Kansas or Illinois are the closest states with legal abortion.

“Now you may call our health centers in Kansas and find out that a whole lot of Texans are taking those appointments and people from Oklahoma and Arkansas, Louisiana,” Wales said.

“And even though you may live 15 minutes across the state line from one of our health centers, you are going to have to wait a long time for care or even be referred to Colorado or New Mexico because we don’t have an appointment quick enough for you to access it.”

In addition, official Missouri data shows the number of abortions performed in hospitals — often because of health complications — has dropped since the state’s ban took effect. The ban’s only exception is for medical emergencies, but the number of in-hospital abortions has fallen from 102 in 2022 to just 29 in 2023. That’s the lowest number in at least a decade, according to an analysis of the data by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Even if Missouri voters approve the abortion amendment, restoring access isn’t like flipping a switch. Setting up new clinics, with enough geographic diversity so that most residents don’t have to travel long distances, could take years. And lawsuits challenging existing abortion restrictions in state law will take time to pass through the legal system.

Jennifer Smith, a St. Louis-based OB-GYN who supports the amendment, said she anticipates that if it passes, finding additional medical professionals willing to provide abortions wouldn’t be a significant issue in the Kansas City and St. Louis regions. But other parts of the state could prove challenging.

“I think that will be an issue,” Smith said.

In the years following the Roe decision in 1973, more than two dozen clinics were established in the state, peaking in the 1980s before steadily declining ever since. By 2017, a Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis was the only one still performing abortions.

Rebuilding access will take time, supporters of abortion rights say.

“We have to think long term about this, and it would be irresponsible to not,” said Mallory Schwarz, the executive director of Abortion Action Missouri.

Schwarz said that despite Missouri having just one clinic offering abortions at the time of Dobbs, the state has a strong infrastructure for sexual reproductive health. Schwarz said that “when we win this, and as we begin the next phases of litigation to challenge the existing laws, that infrastructure, those providers, are itching to be able to reopen this line of care.”

More out-of-state travel

Interstate travel for abortion has exploded in recent years. Between 2020 and 2023, the percentage of abortions obtained by patients traveling out of state grew from 9% to 17% nationwide, according to Guttmacher.

In Kansas, the percentage of out-of-state patients jumped from 52% to 69%. In Illinois, the percentage went from 21% to 41%.

“Traveling for abortion care requires individuals to overcome huge financial and logistical barriers, and our findings show just how far people will travel to obtain the care they want and deserve,” Isaac Maddow-Zimet, a Guttmacher data scientist, said in a statement.

“Despite the amazing resiliency of abortion patients and providers, we can’t lose sight of the fact that this is neither normal nor acceptable: A person should not have to travel hundreds or thousands of miles to receive basic health care.”

Jocelyn Frye, president of the National Partnership for Women and Families, told a U.S. Senate hearing in June that most women seeking abortions already have difficulties paying for food, housing and transportation. Any additional costs associated with traveling for an abortion present a substantial barrier to access, Frye said.

A 2023 study published in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management found that an increase from zero to 100 miles in the travel distance required for an abortion was estimated to reduce abortion rates by 19.4% and increase birth rates by 2.2%. Another 100 miles reduced abortions by another 12.8% and increased births by an additional 1.6%.

“For many, being forced to travel often pushes abortion care entirely out of reach,” Frye said.

Some anti-abortion activists say that since Missouri’s ban took effect, state lawmakers have shown a greater focus on pregnant women and mothers. Lee pointed to an additional $2 million appropriated by lawmakers this year for alternatives to abortion services — above the $8.6 million already budgeted.

Missouri’s Alternatives to Abortion program provides pregnant women and new mothers with free assistance, including supplies, drug and alcohol treatment and transportation aid. Critics say these kinds of programs effectively operate simply as an effort to dissuade women from having abortions.

Lee said the major needs of clients of pregnancy centers and maternity homes are child care, housing and transportation.

“Those are determining factors for women,” Lee said.

Growing role of medication abortion

As abortion bans have taken hold in Missouri and elsewhere over the past two years, providers have increasingly turned to medication abortions.

Medication abortions accounted for 63% of all abortions in the United States in 2023, according to Guttmacher data, up from 53% in 2020. In Kansas in 2022, the last year for which full data is available, 59.6% of abortions were attributed to mifepristone, a common abortion drug that extensive research has shown is generally safe.

Mifepristone holds the potential to significantly undercut abortion bans if patients can obtain the pills through the mail after a telehealth appointment — eliminating the need to travel to another state.

The FDA has approved mifepristone for online prescribing and mail delivery, but Missouri law requires that when any drug is used to induce an abortion, the initial pill must be taken in the presence of the prescribing physician. In Kansas, Planned Parenthood Great Plains offers medication abortion via telehealth but requires that the first pill — mifepristone — is taken at a clinic.

Missouri Republicans have fought to limit access to mifepristone. While the U.S. Supreme Court in June tossed a challenge to the drug on procedural grounds, Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey and Kansas Attorney General Kris Kobach are continuing to pursue a lawsuit seeking to overturn the FDA’s approval of the medication.

Bailey and Kobach have previously argued in court papers that their states were affected by the FDA’s decision allowing abortion medication by mail because it could lead to people in Missouri receiving the medication despite the state’s ban. They also argued that the states would have to contribute more to Medicaid because women could end up in the emergency room after taking the drug.

A group of Texas doctors had sued to block the FDA’s decision, but the U.S. Supreme Court found they lacked standing to challenge the authorization. The doctors were represented at the Supreme Court by Erin Morrow Hawley, an attorney with Alliance Defending Freedom and the spouse of U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican.

Bailey and Kobach — along with Idaho — say their challenge won’t be dismissed for lack of standing.

“My case is still alive at the district court,” Bailey said on social media recently. Referring to Hawley, Bailey said, “We will zealously continue her great work to protect both women and their unborn children.”

The outcome of the case is critical to the future of abortion access in Missouri. Even if voters approve the amendment in November, a federal court decision severely restricting mifepristone would prove a big obstacle to providers’ efforts to offer abortions in the state.

But if voters approve the amendment and the legal challenge fails, the Missouri Constitution will almost certainly protect wide access to mifepristone.

“Part of the role of the campaign is increasing people’s awareness of what it means to live in a banned state,” Schwarz said, “and then empowering them to understand that we can change this, and we can do it now.”