Napoleon Dynamite 's ‘Vote For Pedro’ T-Shirt: A Definitive Oral History

Photograph: Everett Collection; Collage: Gabe Conte

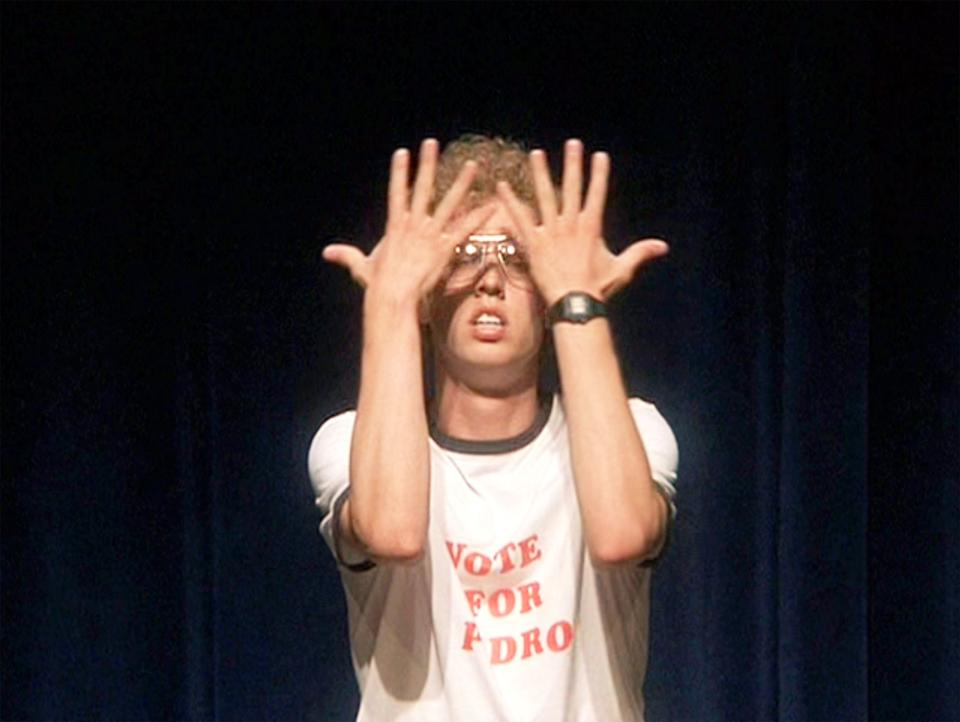

In the 2004 indie flick Napoleon Dynamite, the film’s title character makes an eleventh hour effort to save his friend Pedro’s long-shot bid for student body president — by getting onstage in front of the entire school and busting out an oddly enthralling dance to Jamiroquai’s “Canned Heat.” Performed by a gangly then-unknown actor rocking a perm, Moon Boots, and a ringer tee emblazoned with iron-on letters reading VOTE FOR PEDRO, the Napoleon Dynamite dance scene went nuclear at a time long before viral memes were a thing, and a year before the first-ever video was uploaded to a nascent platform called YouTube.

Driven largely by word of mouth (with an assist from MTV), Napoleon Dynamite—made for $400,000 by first-time director Jared Hess and a crew of Utah film school graduates, starring Jon Heder as an awkward rural teen who spends his days spinning grandiose stories about his Bo-staff skills—became a box office juggernaut, grossing over $44 million domestically. But the Vote for Pedro shirt itself, a last-minute idea that costume designer and co-writer Jerusha Hess came up with and made by hand during the film’s scrappy Southern Idaho shoot, was arguably what catapulted Napoleon Dynamite from indie hit to pop culture canon.

The classic-looking tee became the de facto symbol of a movie rife with memorable oddities (a pants pocket for tater tots, drawings of “ligers,” etc), but it also came to symbolize a particular time in the early aughts, when quirky comedies like Garden State, Little Miss Sunshine, and Juno had mainstream attention outside left-field subcultures, and ironic graphic t-shirts flew off the shelves at retailers like Urban Outfitters and reigned supreme within fashion.

Introduced as part of a broader merch line as the film’s profile grew, the “Vote for Pedro” shirt—much like Napoleon Dynamite itself—changed the fortunes of everyone involved and helped steer retailers like Hot Topic toward a more merch-driven business model. On the 20th anniversary of Napoleon Dynamite’s limited theatrical release, this is the story of how an ad hoc costume choice in a fringe indie film became a massive pop culture moment, as told by the filmmakers, the cast, crew, former executives, Hot Topic employees, and the shirt’s licensees.

napoleon hands

CBS Photo Archive/Getty ImagesIn 2003, Jared and Jerusha Hess were recently-married college students studying film at Brigham Young University. Jared had written and shot a short film, Peluca, based on his experience growing up in the small rural town of Preston, Idaho, that became a proof of concept for Napoleon Dynamite.

Cory Lorenzen (Napoleon Dynamite production designer): All of us met at BYU. I was studying design for theater and film, Jared was studying direction. Jerusha was in the school too. Our producer, Jeremy Coon, was in that producing program there. Our DP had gone to school there—he was a couple years older than us and was working in the local film and commercial scene. There was a lot that was being shot in Salt Lake at the time, not only things like features or TV series but also independent films.

Munn Powell (Napoleon Dynamite cinematographer): BYU is very unusual in that film students have access to a lot of production equipment. And they had an onsite laboratory, which was just bonkers.

Jeremy Coon (Napoleon Dynamite producer and editor): The best thing I can say about the film program is that if you were proactive, like Jared and I were, you could just do whatever you wanted. Like, they let you have equipment.

Jared Hess (Napoleon Dynamite co-writer and director): The faculty at BYU were just amazing.

Jerusha Hess (Napoleon Dynamite co-writer and costume designer): They said, “Yes, go shoot things. Go, here's money. Here's film stock.” And this is back when film stock was so expensive, and they put cameras in our hands. And we took advantage of every opportunity while at school.

Tim Skousen (Napoleon Dynamite first assistant director): We just all hung out together, we made movies together for years. I used to edit all of Jared’s movies when he was in film school.

There were two groups at this film school: There was one group that was doing, I would say, serious sci-fi type stuff. And then our group was this mixture of comedy and art. We all liked Wes Anderson. I mean, he had just had Rushmore come out and we really liked Bottle Rocket. So we were in the right place to be interested in comedy that had a dryness to it, kind of the tone that you would see in Napoleon Dynamite.

Lorenzen: [Jared and I] worked on a couple little films here and there….we actually came to LA to work on a little short film by a guy named Rob Thomas, who eventually created Veronica Mars and Party Down. Jared was always in the camera department. I was always in the art department. A lot of times when we were doing these other little projects together, we'd always talk about, “Hey, when we're doing Jared’s film, we'll do it this way.” A lot of that time was spent talking and hopefully planning for what our future work would be.

Powell: We worked together on different student projects for a couple of years, until [Jared] went on to serve a mission for the LDS church. But right before he left, he's like, “When I get back, we're going to shoot a feature film together. And I was like, “Whatever, dude.”

Yuka Ruell (Napoleon Dynamite costume department and actor): Jared introduced me and my future husband [Aaron Ruell, who plays Kip]. And then I was friends with Jerusha, and we introduced Jerusha to Jared.

Skousen: Jared and Jerusha were people who were early married in our group. Most of us were just single guys. And so I would just stop by and we'd hang out, we’d talk about scripts.

Jared Hess: Jon Heder was studying to become an animation student, but he was in a lot of the film classes. I’d written this short film called Peluca, which was the beginning of the Napoleon Dynamite character, and was like, “Oh my goodness, that guy can play an awesome mouth breather.”

Jon Heder (Napoleon Dynamite): When I read [Peluca] we were both kind of like, “Oh my gosh, we are 100% in sync with who this character is.” Like, I know this guy. This is me and my younger brothers. I made homemade nunchucks. I was pretty good with a Bo staff. At least, I thought I was pretty good with a Bo staff.

Jared Hess: [Jon] was kind of a cool dude. He had a twin brother and they would, like, go to dance clubs and do these weird twin choreographed dance routines. And so Jerusha was like, ‘You're gonna have to perm that man's hair to, like, really get him into the role.’

Heder: My brother, I think we danced together freshman year. I'm not sure exactly where they heard that from. Or that word got out. But there were definitely, like, solo dance sessions that I had done.

When we started talking about getting ready for the short film, [Jerusha] was like, “Jon, what do you think about getting a perm? How do you feel about that?” I didn't tell her this, but in my head, I was like, Aw, man. I'm still single. I'm still trying to find a lady friend. I'm still trying to hit the dating scene. I wasn't a big dater, but I was definitely interested in girls. And I was like, Hmm, a perm…that’s not gonna help me out. [Then] I was like, “Let's do it. It comes out right after, right?” She's like, “No. It’s called a ‘perm.’ It's—permanent.”

Jared Hess: We sent him to this hair academy in Provo where they use people's hair as guinea pigs. They permed his hair for free.

Around the same time, Jeremy Coon, a friend and fellow BYU classmate of Jared, Jerusha and co, had been wanting to produce a film. His older brother Jonathan Coon — who started 1-800-CONTACTS in his BYU dorm room in the ‘90s and had taken it public in 1998— agreed to financially back the venture.

Heder: [Jared had befriended Jeremy] and told him his dreams of making a feature film while he was a student: “I just need some money — probably not tons and tons of money — but just some money because I know I can get everything else put together here and shoot a movie in Preston that’s about some weird kid.”

Coon: My brother, he basically agreed to put up some money for me to do a feature film. And then after working with [Jared on Peluca]. I was like, “This is the team I want to bet on.”

Heder: Peluca, once [Jared] put it in the school festival and a couple of other [film] festivals…that’s really what the short film did for him. He’s like, “This works. This shows me this character works, this world works.”

Coon: My brother went to that [Peluca Slamdance] screening just like “Oh, this seems funny. People are reacting to it. I don't feel bad about putting up money.”

Skousen: Napoleon Dynamite, at the very beginning….that character wasn’t even the character. It was a guy going around a field making fake crop circles in Idaho. And then he abandoned that, and he and Jerusha worked more on the Peluca character as Napoleon Dynamite.

Jerusha Hess: We were literally just these kids in this rattletrap apartment. We couldn't afford a computer, and so our friend lent us this old, old Macintosh, when they were called Macintoshes. It was one of the bubble ones that had, like, neon blue casing. He lent it to us knowing that we were trying to write a script. Jared and I had one chair in the house that we also kind of just borrowed and stole from BYU. We sat at that desk and just typed out Napoleon so slow, and midway that computer started smoking.

Jared Hess: It started to have electronical issues and it would catch on fire. But it stayed alive long enough for us to finish the script.

Lorenzen: There was a lot of anticipation to getting the script, because [Jared had] been talking about it for a year and a half or two years before it actually came through.

Jared Hess: We both come from families of lots of boys. I have five younger brothers, I'm the oldest of six boys. [Jerusha] has seven brothers, she’s the only girl. And so we have a lot of overlap in our experiences. Everything that Napoleon and Kip do, their relationship, is probably like the strangest sibling moments that we both had growing up that made their way into the script. When Napoleon calls Kip to get his Chapstick? That really happened. [My brother] called me one time and asked for Chapstick when he was still in school.

Coon: The initial check was for $200,000. And then when he gave it to me, he goes, “Look, if this goes nowhere…you're still my brother. Just don't ask me for money again.”

Skousen: Jeremy Coon had access to some funding, and he really decided that Jared was the guy he wanted to back. And so Jared came out of school, and basically had this huge opportunity. And we just employed each other, we got some people out of LA to help out.

Ruell: My background is actually in post production. I was working on Bad Boys II or something in LA. And that was coming to an end, so I had the summer free and I was just wanting to help, And I was just going to do whatever they needed me to do. And that was the wardrobe.

Haylie Duff (Summer): My manager sent [the script] to me, and she was like, “This seems weird. I don't fully understand the humor.” The script itself was very funny, the way that it was written out.

Diedrich Bader (Rex Kwon Do): I was always looking for something to do in the summer, between [seasons of] The Drew Carey Show. We were in between our eighth and ninth season, and the timing was perfect. To this day, [Napoleon] is still the funniest script I've ever read. Seriously, honest to god, that was why I did it. Everybody but my wife discouraged me from doing it, because they had no money. My agent was like, “I don't know what's happening with this.”

It made me laugh harder than any script I've ever read, including Office Space, or any of the sitcoms I've been in. And part of what made me laugh so hard gets into the idea of Vote for Pedro. Because the thing that I look for anyway — and I've done some real stinkers — is a distinct voice. Something that's really, truly original. And that script is…I mean, that's the most original thing anybody could ever write.

Shondrella Avery (Lafawnduh): I had a show called Girls Behaving Badly with Chelsea Handler. We played pranks on people. We were doing pranks across America, and we had a break in Chicago. My agent called about this particular film. I went to Kinko's, I read [the script]. I figured either it was the weirdest, funniest thing I ever read, or I was the corniest Black person I knew. Probably a little bit of both. And I said yes.

It had no money attached to it. But it just had this really awkward thing about bullying, and the anti-bullying of it all. And I came from the inner city, so for me…I'm six feet, I always was different. I only went to one year of public high school in the community. Other than that, I lived with this wonderful Irish family during the weekdays to go to private school in an all-white area. So my upbringing was very awkward and very different, and this film felt like that for me. I was akin to it.

Tina Majorino (Deb): I had taken a break from acting to go back to school and recalibrate a little bit, have a real life. And then I decided that I was ready to come back, and I think the Napoleon script was maybe the first or second script that landed on my desk. Most of the time when you get scripts, you see potential, or you like the story, but some things need to change. To me, it was perfection. It was so new and interesting and different and funny. My career, up until that point, I mostly did dramatic roles. And I had a really difficult time having anyone see me for comedies.

Efren Ramirez (Pedro): At that time, things were not so easy for me. I was living with my friends and friend’s family out in Pomona, which is about an hour away [from LA]. And I would drive out and audition so many times…my agent called me up and said “Listen, you have an audition for The Alamo, a feature film. Then you also have an audition for Napoleon Dynamite.”

When you're starting out, they don't give you the script. You just get the pages of the script. And then I read Napoleon and thought, “This is weird, what is this?” The first scene was about running for president. And the other thing was the speech. When I [auditioned and] did the speech, the director kept on telling me: “Slower.” So I did it slower. Then he said, “Slower.” Then when I was done, I went home. My agent called me up and they said, “Listen, you booked these films but they [shoot] at the same time.” I made the choice to do Napoleon Dynamite.

Once the money is locked in and the actors are on board, the cast and crew head to Jared’s hometown of Preston to shoot Napoleon Dynamite in the summer of 2003.

Jared Hess: Jerusha I worked on the script and got it as lean as we could. We had 23 days to shoot it.

Coon: I know we had to wrap in July because the rodeo was coming to town. Jared, being smart as he was, wrote the script around locations. So we could do whatever there, which definitely made things easier.

Heder: They might have said Hollywood was coming to town, but little did they know, like, “Dude, we're just a student film crew from right over the border coming up.” Most of the crew were just people I knew. Either they had just graduated, or they've been working in the Utah film industry for a little bit [or] taught at BYU for a second.

Coon: [Preston] is a town of 2000 people, and we all clearly stuck out. We’d be shooting or walking down the street and like a pickup truck would drive by and be like, “Hollywood!” The city just opened up the doors to us. Basically the mayor was like, “What do you need? You need streets shut down?” They always referred to what we were doing as “Jared’s video.”

Skousen: It’s a kind of town where people make up their own fun. You know, they'll do a thing called riding the poop chute, which sounds gross. And it is kind of gross. But during the spring the irrigation water comes in, and they have all these irrigation canals. And a couple of them have, like, bridges to get across the ravines. So people would just jump in, and you’re in there with dirt and mud and a little bit of cow patties. But then when you get to the poop chute, if you will, it would get narrower and get really fast. So you'd be going down this irrigation canal kind of slow and then suddenly it would launch you through…like you're going through rapids and come flying out the other side. It’s a low budget waterslide, basically.

Coon: There's one hotel in Preston, the Plaza Motel, and it couldn't accommodate all of us because it didn't have enough rooms. We put most of the cast up at the Plaza Motel. But the rest of the crew had to find people's houses.

Heder: They put the actors up in the motel where the walls could bend. It was made of that fake wood paneling.

Skousen: We all basically stayed in people's homes, which was the only way to really afford it. I stayed at some friend’s house in their converted barn.

Lorenzen: I stayed at Jared’s grandma's house.

Coon: It felt very much like a summer camp.

Bader: It was a skeleton crew. One electric. One grip…it just was tiny. I just love that. I just love that people want to do it because there's a love for it. That’s why I do so many student films.

Majorino: They were really, really well organized…not having a lot of money means that there is no room to fuck around. You show up and you are prepared, which I think all actors should be anyway. But that doesn't always happen. There was a directive that all of us knew what we had to do, and we did it. There wasn't room for doubt, or questions, because we didn't have any. Because it was either on the page, or Jared just would tell you.

Jared Hess: Most of the time, I'd only be able to afford to shoot two takes max of something before we had to move on, and just because we didn't have it in the budget to play around. So we had to show up as prepared as we could be.

Coon: Back then digital wasn't really feasible. Back then you'd still have to go out to 35 millimeter if you want to show in theaters, which is what we wanted to do. Just the film stock…out of the $400,000 that was spent on the movie, half of that is related to film costs.

Powell: I just wanted to feel a little hazier than even film stock usually is because to me, southern Idaho was like it was sunny and bland and a bit dusty. Some people think that's tapping into nostalgia, which wasn't overtly my intent by diffusing it that way. But especially in the houses, I wanted it to feel like there's a little bit of dust in the air.

Skousen: Jared just has so many stories about growing up there. Like the stories of Dale Critchlow, who played Lyle, who shoots the cow. That guy had been in two tractor accidents, had supposedly been hit by lightning one time. And [Jared] would have to tell him like, “Now Dale, you and I know that you would never shoot a cow in the back of the head with a shotgun. But this just looks better for the camera.” Because he was confused: “Why the shotgun? You need a pistol for this.” So many of the smaller roles were just people that Jared knew growing up. I mean, that bully character literally was a bully that bullied his brothers.

Powell: There were crazy hurdles that happened. When we were going to shoot the scene where Lyle, the local farmer, is supposed to be putting this cow down, it's gonna be butchered for the family. And we get out there and we're getting ready for that, and we're hearing there's no cow. And so somebody is trying to find a prize cow that they can run over to us.

Skousen: There were just interesting characters who would come around. Like Napoleon’s house, all the interiors were shot at the candy man's house. And the candy man was this old guy who would just walk around with candy, which, you know, could be viewed as creepy. And he would also give us, like, old special dimes. So for years, I carried around this dime he gave me from 1921 or something like that. But then I think I lost my wallet, I don't have it anymore.

Avery: If I ever was popular, it's in Preston, Idaho. There were no Black people there at all, except for me. So there were these creepy white men around the trees just looking at me. Like they had never seen a Black person…I mean, staring. And they would come to every place they saw me performing or while I was working. I was in the local paper.

Ruell: Haylie Duff, she had brought this little toy dog with her and set its leash just under the leg of a chair. And then she went off to shoot and then, of course, it broke free and was running all around the little town. And we were looking for her dog. And then we would eat lunch at one of the two fast food places in town. And we would roll up and like get lunch and they're like, “oh, heard you lost your dog.” The whole town knew what we were doing.

The Vote for Pedro storyline was always a part of the Napoleon Dynamite story, but the shirt itself wasn’t in the script. Then the cast and crew started preparing to shoot Jon Heder’s dance scene, where he dons the shirt to help boost his friend Pedro’s chances in the student body president election.

Jerusha Hess: We had very specific [wardrobe] notes in the script. There's all these descriptors about Moon Boots, Hammer pants, and weird things. And I shopped all over Utah, Idaho, and even in California at these local thrift stores called Deseret Industries for all those silly t-shirts, and I found some really good ones. Like, there's one that says Ricks College, which is a local Idaho college. There’s a horse that says “endurance.”

Ruell: We just went there to find, I would say, the majority of the wardrobe. So yeah, not very glamorous. We were just trying to find things that would feel authentic to the characters, but on a budget.

Jerusha Hess: It’s probably also a product of [us] growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, kind of not very affluent, and always wanting to look like the kids who dressed a certain way. We had to get scrappy with our weird thrift store outfits, and had to develop our own style from Ross Dress For Less. And I think it just makes you aware of clothes and what people have and don't have, in a funny way.

Jared Hess: I moved to Preston when I was a sophomore. And totally felt like an outsider. And then eventually, I ended up running for student body president. The skits and the elections and the assemblies, they're a big part of that small high school culture. And so that just easily found its way into the script.

Jerusha Hess: It always was the story of Napoleon helping his friend win the election. We had never planned for a Vote for Pedro t-shirt. That was never written. Of all the costumes that we wrote in, and all the details, that wasn't something we had thought out. The night before, I just thought, “Wouldn’t it be funny if he made his own t-shirt?

Coon: Jerusha made it the day before as an afterthought.

Jared Hess: Literally, we were shooting the scene when Napoleon gets on the school bus and he's got the headphones and he's going to school. So that day Jerusha was like, “Oh, it seems like Napoleon should be wearing this [shirt].” She'd gotten this thrift store ringer tee, went and bought some iron-on letters and just made the Vote for Pedro t-shirt.

Jerusha Hess: The inspiration for that was, in Utah, there’s a lot of family reunions that have [shirts] that say “Miller Family Reunion 2024.” And back in the day they were just ironed on letters. I'm pretty sure this shirt came from Old Navy. It was new. And the iron-on letters were from Walmart in Logan, Utah.

Lorenzen: The font she chose was called Cooper Black, which was a font that I think came around in the 1930s. It was really popular around the mid century, especially in the 70s and 80s. And I think that font choice, more than anything else, was a real key to the look and aesthetic and the success of that shirt feeling like it belonged in that Napoleon world — which is a pretty unique and interesting and pretty distinctive world.

Ramirez: She was very specific about what would identify a character like Napoleon. It was also understood that he had such a unique style. So when you see a ringer t-shirt like that with all those words — Vote for Pedro — even one of the o's is kind of bent a little. That was different.

Lorenzen: One of the things I think I really liked that [Jerusha] did was she made it look imperfect on purpose. The letters aren't even, they're a little crooked, they're spaced out a little awkwardly here and there. It's really cool because in the scene, Napoleon just shows up wearing the shirt. And you can tell it's homemade. And then you as the viewer — at least for me — I imagined him that night before, like, actually making it. It’s this bit of backstory that your brain just puts together really quick.

Jerusha Hess: They have come up with so many quirky details over the years that Jared and I are like, “I don’t even know, guys!”

Jared Hess: They’re rewriting history!

Jerusha Hess: So it is DIY, there was no stopping it being DIY. There was no ruler. There was no pencil guide. There was nothing but: “Let's just make a funny shirt that Napoleon obviously would have made.”

I was seven months pregnant while I shot that movie. Or eight months. I was just really depressed and hot and sweaty the whole time. And so I made a matching shirt for myself, but it didn't say Vote for Pedro. It said: “You can do it!”

Ruell: Her shirt said, “You can do it!” Which I think we probably needed to believe at that moment. I mean, there was a lot riding on that film, especially for them just financially…It was just kind of like: “Can we make a living as filmmakers? Like, we are using someone else's money and we need to make something of this.”

It was so hot. I actually think sometimes the heat affected the performances. Especially for Pedro and Napoleon when they would be, like, in the school, and just so deadpan and so almost comatose. And I think it's partly because it was approaching 100 degrees. I’m sure [Jon’s] feet were sweating buckets in those moon boots.

Majorino: Seeing [the shirt] on Jon for the first time…I can't really tell if this is an opinion that I have because it became, like, this cultural phenomenon. But I do remember seeing Jon in that shirt for the first time and being like, "That's iconic.”

Coon: It was always building up to that moment, [the dance scene.]

Heder: It was not choreographed. The whole production I just told Jared, “All right, what exactly are we doing for this dance scene?" And he's basically putting it in my hands. He’s like, “just do what you do, man. This is your thing.” I didn't really know where to begin, because that wasn't something I did. I was like, “I guess I'll just do what I normally do.” Which is just freestyle dancing.

The only thing was the night before we shot the dance scene I took Tina Majorino, who had little experience, to Rex Kwon Do studios. I want[ed] to figure out the first—and I didn't know this term until she told me—two eight-counts. I just want to figure out the opening, because we didn't know the song we were going to be able to get the rights to.

Lorenzen: Jon was too embarrassed to do that dance in front of anybody. So there were three people in the room. I snuck in the back with Jared with Jeremy Coon.

Coon: I think he asked me to leave and I said, “I'm not leaving.” I was just like, “I'm paying for all this, I’m the editor. There's no reason I need to go sit out in the hallway.”

Heder: Everybody kept trying to make excuses for why they could be in there. But I was like, “No, nice try, sound. You don’t need to be in here.”

Duff: It was very secretive, like, “He's been practicing this dance!” Nobody was allowed to stay and watch. This was a full audience of people, so our reactions to him dancing are not to him actually dancing.

Skousen: We were playing mostly Jamiroquai, we played some Michael Jackson, he started to play, like, a Justin Timberlake song. And [Jon] just got up there and just danced.

Jared Hess: We basically had three takes to pull it off, so we did only three takes of the dance. And it was not one fully choreographed routine. We played a different three-minute song for each take, and then we basically took the best highlights, the best dance moves, and then cut them together as if it were one single routine. If you look at the transitions, there's weird transitions between moves. It's very, like, montage-y. I'm shocked that high school kids since then have figured out how to do it as one complete dance routine, because it was never designed that way.

After the film wraps, everyone goes back to their lives — booking other jobs, working, studying. Then, the nascent film gets an unexpected boost.

Coon: We had made the movie thinking, “Well, there's at least a market for this in the mountain region of, like, Utah and Idaho.” And around that time, there were some regional films that were being made. So we knew there was an option of self-releasing and playing theaters and going from there.

Skousen: So at that time in Utah, there was a flourish of Mormon-based films, which they called Mormon cinema. So the other group [from BYU film school] went off, and even though they were into really cool sci-fi stuff, their first film was a Mormon adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. And they got the funding for it the same summer we did. They went to a local restaurateur and got a bunch of money. So we were in Preston filming and they were in Salt Lake filming. And we both wrapped during the summer. We were both in post getting the film made.

It was November, and I remember looking up and seeing the billboard for their film. Their film was going to be in theaters in December. And I was like, “Oh my gosh, did we blow it?” I’d seen the rough cut [of Napoleon]. And we thought it was hilarious. But we had just made a film just for ourselves, like things that we found funny. And it was like a week later that Jared called me and he's like, “Hey Tim — we're going to Sundance, baby!”

Trevor Groth (former senior programmer for the Sundance Film Festival): I was the first programmer to watch Napoleon Dynamite when it was submitted to us. I grew up mostly in Salt Lake City, but…I actually have family in Preston, Idaho, too. So I instantly recognized the landscape and was, all of a sudden, just completely engrossed in the film. When I saw these wonderful and magical and incredible characters that unspooled as the film went on, I instantly fell in love with it.

I was ready to go to the mat for it, because I didn't know if it would necessarily connect with everyone. I knew why it should be in the festival. But I will say all of the other programmers, in their own way, responded to it and thought it should be in the festival. It wasn't a fight. So it really was a very natural fit to be in competition.

John Sloss (Film sales representative for Napoleon Dynamite, founder of Cinetic Media): One thing we do is sell movies at film festivals. I often say that the most reliable genre of film is the new — something people haven't seen before. And this basically came from outer space. This pretty much came over the transom, and we watched it, and we loved it. Our strategy was to not tell any of the buyers about it, because we thought it would be a huge discovery title. And to let people discover it and embrace it at Sundance.

Groth: I loved Napoleon Dynamite so much that even during that crunch time, I watched it several times. I just couldn't get it out of my head. And I started, like, quoting it. No one had seen it yet, it didn't make sense what I was saying. But I really loved it. I thought it would be something very special.

I saw it in the fall when it was submitted to us, and then the festival takes place in January. And in that window in November, a friend of mine does an annual roller skating birthday party and people can come dressed however they want. And I actually made a Vote for Pedro shirt and wore it to that roller skating party. Again, before anyone had ever seen the movie and even premiered yet at Sundance.

Napoleon button

Fred Hayes/Getty ImagesCoon: I went online and ordered up 5000 Vote for Pedro buttons, and then 1000 Vote for Summer buttons, and had them shipped to Jared’s apartment [ahead of Sundance]. It was a last minute thing because our sales agent said, “you need to do something, and this is a perfect fit.”

Jared Hess: Everybody's wearing these things [around Sundance], like, “Who's Pedro? Vote for Pedro, what's that?” And so it just created a lot of questions. We did not have Vote for Pedro t-shirts at the festival. It was just the buttons. And it was a real horrible font, by the way. I think it was like, Impact font. It wasn’t the cool vintage lettering that was on the t-shirt.

Heder: Yeah, we did our groundwork of giving out the buttons. But we had a lot of emotionless faces looking back at us, like, “what is this?”

Sloss: We gave the Pedro buttons to people we wanted to buy the film, and we gave the Summer ones to the people we didn’t want to buy the film. I don’t think they were aware of it.

Jared Hess: So the movie premiered at The Library on a Thursday night. We had not screened the movie for anybody at all. We just barely had finished it, and I was dry heaving my brains out, like: “This will either be the beginning or the end of our career.”

Skousen: He was throwing up on the way to the theater. He was so stressed out because all these people come out of the woodwork when you have a film at Sundance [who] suddenly want to be your best friend. And you don't know who to trust and who to listen to.

Jared Hess: I knew that it was specific, knew that it wasn't going to be for everybody, but the Sundance audiences are incredible. And all the buyers were there, the studios, all the acquisitions people. It screened, and it got a standing ovation.

Avery: We were in the back in the corner, just mesmerized. And I just remember thinking, “this is really special.”

Majorino: There was not an empty seat. People were standing, like, filling the aisles. And I remember it was so special because I'd never seen the movie with other people like that. And I was a mess. I was like, sobbing in the theater, because to see people's reactions…they were screaming and cheering for Napoleon. I was like, “Holy shit.” You could feel it. Like, I'm getting full goose right now. Because it was electric.

Sloss: I was joking that it’s like they put nitrous oxide in the vents or something. People just went berserk.

Ruell: There were rumors that John Sloss had, like, turned down the temperature in the theater…maybe it makes them pay attention to the film or have some anticipation or something.

Jared Hess: Immediately our film rep sales rep at the time, John Sloss, was like, “You know what? I've gotten offers through this screening. I'm just not even answering them. We'll get into it early tomorrow morning.” So then there was the bidding war and all the different studios had offers for it.

Troy Craig Poon (former head of acquisitions, MTV): The Library Theater is basically a library that they've converted to theater, so it has a very low ceiling. So as a result, it's an amazing theater for comedy. The thing about comedy is it’s very contagious, so if you hear one person laugh it starts to snowball.

As an independent film person, as a person of color, I've always rooted for underdogs. And I thought the message [of Napoleon Dynamite] was the perfect message we wanted to send out to young people. I did acquisitions for a long time. And one of the things you have to do is you watch a lot of films, and you have to assess: “Okay, I may like the film personally, I may even love the film personally. But can I find a way to connect it to an audience?” And with this particular film, I felt really strongly that it was the right message, and we could get it out there.

Duff: Nobody was talking about it. And then the next day, it was like everywhere we went, somebody was talking about it.

Avery: The next day, I remember seeing all these cardboard signs on the main street: “Lafawnduh.” And I just thought, “wow, look at this, people want to take pictures.” And then it was like five, and then 10 and then 20 people just hovering around us.

Bader: I regret that I did not go. That's one of my few showbiz regrets. I was developing something for CBS…but I was hoping to get a pilot shot at the end of The Drew Carey Show. And I had just gotten network notes. And it's funny, because we never shot the pilot. I regret it, but at the same time, I had to fulfill my professional obligations. I had friends that went to the Sundance Film Festival. A bunch of them. And they were all like, “Oh my god, dude. It was huge.” And I was like, “Napoleon was?”

Majorino: I was planning on driving out, going to the premiere, hanging out, and then driving home. So I brought one outfit. I mean, literally one pair of jeans, boots, and I was wearing my snow coat and a sweatshirt. I ended up staying nine days.

Lorenzen: We tried to get into one of the little [Sundance] parties and they said, “No, it's a closed party.” And then one of us said, “We made Napoleon Dynamite.” And they said, “oh, okay, you can come in.” That was the first time somebody had acknowledged that there was value to what we'd made and what we'd done. It was just…a put on by some agency party deal. But to us it was like, “Wow, people have heard of this.” Even people outside of the theater.

Skousen: We were not naive…we live here in Utah. So we've worked at Sundance. We're pretty aware that at Sundance, you'll have 170 films, and like only 60 of them will get distribution deals and only really like 10 of them are good distribution deals. We knew going in there that there's a chance nobody likes this film, and nothing happens with it.

Sloss: It’s fable or legend at this point, but we have a condo out in Deer Valley that we stay in every year. And if we have a popular title, people tend to migrate over there. We will often arrange meetings between interested parties…in my experience, the more buyers talk about what they want to do with the film, the more excited they get about the film. So it's a self-fulfilling exercise.

And we ran that in a fairly orderly way. All the interested parties came by, made their presentation. Sometimes you'd have more than one at a time in the condo, and one group would be upstairs and the other would be downstairs, and we shuttled filmmakers between them. It was pretty dramatic.

Poon: For this particular film, they said, “Listen, we're going to set there's a lot of people interested, we're going to set an appointment for you, I think it was at one o’clock. I get a call Sunday morning, maybe around 10 or 11, and they said “sorry, but the film has been taken off the table, we're canceling your appointment.” And I was completely devastated. I found out Fox Searchlight had taken it off the table. Fox Searchlight at the time, they’re kind of like what A24 is now.

Jared Hess: We had our hearts set on Fox Searchlight. They'd done so well releasing films that did not have big names to them, and really got behind what it was. They were always our dream for where this would land. Peter Rice was running Searchlight, and his team just totally got behind it and made the deal. They all showed up, every department, and said, “Look, this is our plan for it. We love this film.” I remember Peter Rice going, “Your film is absolutely joyful.” Didn't say it was funny. He said it was joyful.

Coon: Jared, Jerusha and I got pulled up to an upstairs bedroom. And then John Sloss ran back and forth. And I think it was like three times back and forth, on a scrap of paper with deal points. And then that was it. I had a term sheet the next day, and it happened so fast. We're getting in the car to go leave and just feeling this overwhelming emotion of like, “what just happened?” I would never run a marathon, but I assume it's what it feels after you run a marathon.

Poon: I couldn't accept “No,” and that I couldn't have it. So I called Peter Rice, who was the head of Fox Searchlight. Peter Rice didn't know me from Adam. On the food chain, I'm like, nobody compared to him. But for some reason, he agreed to take my call. And so I went to go see him for breakfast. And I just went to him, begging, and said: “Listen, Searchlight is amazing. MTV hopefully can bring a lot of value to this film. And if we could figure out a way to partner if you'd be open to us partnering, I think it'd be a really amazing marriage.”

And I think most people would have said, “Thank you but no thank you. We've got this.” But Peter’s a very smart man, and he realized that there's some value to what I said and that bringing in the MTV brand couldn't hurt. And so thankfully, Peter was gracious enough to let us partner.

Following the bidding war at Sundance, Fox Searchlight and MTV team up to release the movie later that year. After a few test screenings, Napoleon Dynamite opens in limited release on June 11, 2004.

Heder: The dust settles and we go back to our lives. And I'm still finishing up school at BYU.

Jerusha Hess: Even though we'd gotten a little bit of money from Napoleon, we still didn’t know what's next. We were just kids.

Jared Hess: We went from all those amazing Sundance screenings, and then we had our first test screening on a school night in Simi Valley. It did not go well. I was like, “Oh my gosh, they're gonna shelve the movie now.” And they were like, “No, it's all good. We're going to do it again.” And they were going to recruit the right audience.

Skousen: They did a test screening where they flew out Aaron [Ruell] and Shondrella [who play couple Kip and Lafawnduh, respectively]. And at the end of the screening, they had them walk out and do a fake proposal. They said the audience just lost it.

Jared Hess: Then they recruited at the Grove — high school students, college students — and I remember they were like, “This tested higher than Star Wars. Congratulations.”

napoleon van

Courtesy Napoleon ProductionsSloss: The sale was easier than the release. The release did not go off brilliantly.

Coon: The film only opened on six screens. It did okay. It didn't do great.

Poon: Three, four weeks in, I look at the numbers, and I have this pit in my stomach. I'm like, Oh my God—is this all it's going to do? Are people really not going to show up?

Sloss: I think it wasn't until like its twelfth week of release that it really caught fire. And I think it helped that we had affiliated with MTV, and they really stoked it a little bit. The deal that it really started gaining steam so long after it was released is very unusual. It would be impossible to do that now, to keep films in theaters that long while the audience builds.

Poon: By their very nature, independent films never really have big marketing budgets. So they don't really justify [spending] the same that you would spend on a Marvel movie or what have you. It’s tricky to get that attention sometimes. And one of the things that MTV would do is we would offer a lot of promotional inventory on our air, so that you’d get a lot of value that you wouldn't otherwise be able to afford.

Skousen: Once MTV came on, and MTV started promoting it, it started to take on a life of its own. Napoleon Dynamite was on TRL, back when TRL was a thing. And they tried to play it as though they just found this random guy in the street. There's something about Jon, with that hair, and that voice, and those glasses, that people instantly think, This person is funny. We were all watching it live when it happened. We were freaking out. And so when the audience reacted like that…that was like an early moment where we were like, “Oh, man. This is going to be big.”

Elie Dekel (former executive vice president of licensing and merchandising at 20th Century Fox): I can't really speak to the box office pattern of the film, I don't recall. But I remember that it had legs, right? It was somehow extending its audience over time. And this is pre-Internet, so there weren't, like, memes. But we were starting to hear…that this Vote for Pedro was gaining some resonance.

Cindy Levitt (former Senior Vice President of merchandising, marketing and licensing at Hot Topic): In 2004, we were already a public company, and pretty big and pretty influential. At the time, we were already introducing licensed products beyond music. We started bringing in what we called novelty and entertainment licensing. But we hardly were able to get exclusives.

We used to divide up in groups and visit stores all over the country for back to school or holiday. And I remember we were on a back to school trip in Houston, and it was summer because it was a bazillion degrees and hot and humid. And I saw that Napoleon Dynamite was playing at this theater in Houston. It wasn't full, but there's probably 50 young people sitting in this theater. And I had some of the buyers with me. I remember I'd never heard such unison, hysterical laughing in a theater together with people. And we were just rolling.

As soon as we got out of that theater…I remember going down the wrong route. So I first called our contacts at MTV, and they're like, “We don't have any licensing rights.” I didn't know it was Searchlight at the time. So then I contacted Fox, and they didn't really have merchandise put together for it, because it was a little tiny indie film. So we said “We want it,” and I think we gave them a big order just for the Vote for Pedro shirts right off the bat. And that was in the summer of ‘04.

Dekel: It was actually in a conversation with Cindy [Levitt] and Hot Topic and the people on our side…where Vote for Pedro was mentioned: “Hey, that shirt's in the movie, we want to do that shirt. We think there's some retro appeal, and we think it's an inside joke.” Right now, those sensibilities seem so common today. But at the time, it was almost subversive. We were used to doing those insider products for The Simpsons, and we were starting to develop that for Family Guy, the “if you know, you know,” type items. And Vote for Pedro fit perfectly in that scenario. But we weren't sure that it had necessarily a market, and that it would necessarily be something people would want to wear.

Levitt: We did not do the licensing deal ourselves. We did it through Mighty Fine, who was a hip licensee. And so they were really fast.

Patty Timsawat (co-founder, Mighty Fine): We were doing t-shirts and apparel for the streetwear market and more like the club kids…selling at boutiques like Patricia Field. And then as we started getting licenses and going more legit we were going into stores like Hot Topic. At that time, licensed t-shirts, like all the studios, they really marketed towards children. And there was this void in the market for adult licensed products. That's where Hot Topic and Mighty Fine fit into the pop culture world, tapping into that nostalgia as an adult.

Guy [Brand], my partner, he was always in contact with Scott [Morton], who happened to be the men's buyer at Hot Topic at the time. [Scott] talked about how he went to the movies, and then we went to the movies that night, saw [Napoleon], saw something there. And then we were off to the races and trying to find who has the rights.

Dekel: Usually, we're not just doing one item, but many items. In the case of Vote for Pedro, that was the item. The rush to market was in 2005, and it was probably…I would imagine Hot Topic got on it early. And then everybody else chased it.

Levitt: We would go in theaters and with notepads and write it all down. So we started with Vote for Pedro, I think we started with the endurance horse shirt also…but then we did the I [HEART] TOTS [shirt]. And we just kept feeding them lines. The magic sauce happens when the creators approve it right away, because so many times the creators or the studio don't want to rock what their vision is. Because no one had a grand plan or a plan or strategy, they let us just do everything.

We got Vote for Pedro shirts in, I believe, by fall of 2004. But what was also going on in 2004? It was an election year. So those shirts blew up.

Jerusha Hess: We were walking our kid out in a mall and we passed Hot Topic. We didn’t know anything about this. We didn't know the merch was getting licensed. And there was a table full of every quote of Napoleon Dynamite, from “tater tots” to “Your mom goes to college.” Every quote was represented on a t-shirt. And Jared and I just looked at it, and we were like, “What is this?” It was the moment when we realized this is huge. It was out of body, like, “What in the world?” We were silent. We were stunned.

Ramirez: It was around the fall when [the film] started to get big. I remember being with some of my friends at the Santa Anita Park mall, next to Arcadia. And there was a Hot Topic there. One of our friends goes, “Hey, they have your t-shirt at Hot Topic! I thought, “Yeah, right, dude.” And we walk in…not only did they have the t-shirt, but they had the blankets, the hats, the lunch pails. They had it all. It took one person to say “Hey, that’s Pedro!” And then it was like a swarm of people, I couldn't get out. People were taking pictures. They're like, “Uh…we're gonna get security.” And they had to drag me out. They pulled me out, and we snuck on the back.

Napoleon products

Carlos Osorio/Getty ImagesJared Hess: You would see it on the street. I remember Denzel Washington was wearing a Vote for Pedro t-shirt in an interview at one point. You would see celebrities wearing them on talk shows and even like Gregg Popovich, the coach for the San Antonio Spurs, he was wearing it during an election cycle maybe four years ago. When the movie came out, we were in Honduras with Jerusha’s mom. And there was a fisherman wearing a Vote for Pedro t-shirt. It just took on a life of its own.

Timsawat: We knew that [Vote for Pedro shirt] was the one. That one was just on constant reorder with Hot Topic. Our screen printer was in our facility, so the t-shirts were probably manufactured in LA. If we didn't do it in LA it was in Baja. But I want to say at that time, we weren't even in Baja yet.

Levitt: It became the best-selling shirt in our history of Hot Topic ever. I think we would have sold half a million shirts in the first six months. And then it became a million plus over the next year. And then it kept going for years. I think there’s been Billie Eilish shirts and probably some anime shirts that have eclipsed it. But at that time, it was by far the single best selling [shirt].

Sloss: The shirts are just so...I mean, they're made to be iconic. There's just something really disarming about them. There’s something ludicrous about it but truly affectionate, and it's lo-fi in a very cool way. And when Heder is wearing it and shows up and does his dance in it, it was a cultural moment. We all knew it was a cultural moment. We just didn't know whether it would get out there into the big wide world.

Powell: Halloween rolls around and I'm talking to Jared and I’m like, “are you seeing this?” At my house, there's kids dressed up like Kip. And there were people who made their own Vote for Pedro shirts.

Heder: I remember when we were shooting the film, we just made jokes and wistfully thought about: “Can you imagine the merch they could do for a film like this, in a world where this was popular?” We were aware that each of these characters have their quotable lines, and they could easily do that. When I started seeing actual pull-string dolls…I was like, “Oh my gosh, this is like my imagination come true.” Like, this is exactly what we were talking about. They had pins and watches. They had all kinds of t-shirts.

Levitt: We kept revisiting the film, and then our stores would ask for more and more sayings from it because it got deeper and deeper in the universe of it. And it just became this phenomenon.

Ruell: What's that toy company? Is it McFarlane Toys? I remember Aaron going in and getting a full body scan. And I think other cast members did this too so they could make these like very specialty figures.

Avery: The person at the time who was representing me…I had already released him, because he didn't understand the big picture vision. But he was resentful, and what he did was he didn't let the [merchandisers] know that I was on to another person. They wanted to do a doll with me, and I missed the production rollout of that, because I didn't know they were looking for me. So eventually, maybe eight or nine months later, somebody ran into my manager and was like, “We've been looking for Shondrella, we couldn't find her. We went to her agent and [he] was like, ‘Oh, she's not interested in it.’” Why would I not be interested in it?

And I remember him eventually apologizing to me, because I called him and I said that was evil. So the whole rollout of the merchandise at the outset, I didn't get my opportunity — because of the person I was with at that time, he lied to them. And by the time my manager tried to go back and reconcile it, they had already done the rollout.

So once I saw the merch in a store on Ventura, and there were these little dolls…I was so happy and excited, because I didn't know what it was gonna eventually look like if I had participated. But when I saw them, I thought, “oh, my god.” So I had mixed feelings. So for a while, I was very sad about it. I'm gonna be honest.

Levitt: Once it proved itself in the back half of 2004, we had to really fight to keep the exclusive [on merchandise]. So I think they granted us six months and we kept it till June [2005], and then it went out to Target and everyone.

Timsawat: [Other retailers] saw it working, and all the kids at school having the Vote for Pedro and all the phenomenon that was happening. We could take orders, but we could not ship them until [after] that moratorium date. I remember the exclusive was over and every single order had to go out that day, and we were scrambling like crazy. Our office was on the third floor…we were throwing boxes out the window, because the elevator wasn’t working. We were just doing whatever we could to get it to the ground floor to make those trucks.

Dekel: Vote for Pedro then drove the much longer theatrical window of the film, because it just started the conversation. Once you saw the movie, it then created a generational conversation of like, “I don't get it, but my kids do.” That took a life of its own also. And then those images and those clips started to get used and enter the media cycles of those days, and it really permeated entertainment culture.

Powell: I was telling Jared, “Oh my gosh, David Letterman just told America to go see the film first one time, and then go see it a second time. Because they’ll think it was funny the second time.”

Coon: I think it had done like $10 million maybe. And my mom wanted me to go hike Kilimanjaro with her. So right at the height of the movie, I go to Africa, and I'm gonna unplug for two weeks. I remember I would find random internet signals and log into Box Office Mojo and see how the film was doing. And I think it went from $10 to $20 million over the two weeks I was gone. And then once it hit there and then went wide after that, and just played for the next six months. It made like $44 million.

Jerusha Hess: It doesn't feel like anything I made or did. It exists outside of us.

Jared Hess: It doesn't belong to us anymore.

Jerusha Hess: No. Which I think is lovely. And a way to deal with, like, “Ooh, we didn’t get any money for that.” Because it's not ours. We didn’t put kids through college through that licensing deal.

Dekel: The typical deal structure is for every product that is sold to a retailer, we would call that the wholesale price, what the retailer pays for the item from the manufacturer. So the wholesale price as a licensor — me, the studio, giving you the rights to make that shirt — I'm going to charge you a percentage of that number to have the rights to make that shirt. So you're going to make the shirt, you're going to sell it for $10. The range is anywhere from 10 to 15% of that wholesale number in the form of a royalty that is going to come back to me, once you collect the money. So the range of royalties depends on how hot a property is. Generally they go to the owner of the IP, and in this case, it would have been the studio. And then they would have participants, actors, producers, distributors, whoever, that gets their piece of the pie.

Coon: We had a piece of it, but…merchandising wasn't like, at the forefront of things. We were not as smart as George Lucas.

Jared Hess: When you’re up at Sundance, the goal is to sell your movie. That was our hope. And at the time, we didn't think at all, like, this small movie that we made is going to have an impact on that level. Who would have thought that this small movie about an Idaho nerd would have any kind of merchandise whatsoever? And so none of us were thinking about it. But then I think when it did come out and did become the hit that it was, they looked for any possible way to monetize it. It was a process of discovery that I just don't think anybody anticipated.

Dekel: Generally it depends who has the leverage, quite honestly. In this case, the buyer would have the leverage. And the buyer in this case also has a consumer products business. And they're going to say, “We want those rights, and we'll manage those rights, and as part of the exploitation of those rights, there'll be revenue.” And the creators, producers who sold us the film will have a portion of that revenue.

Sloss: [The deal was] pretty standard. I mean, it wasn't going to be about holding their feet to the fire about how much they were going to spend. In my experience with Fox Searchlight, when they're genuinely enthusiastic about something, they will deliver.

Jerusha Hess: We have no ill feelings, because this movie isn't even ours anymore. Everyone loves it. And it gave us the chance to make the next movie.

Skousen: We still do make money from merch.

Coon: We ended up suing over the movie profits and stuff like that. And in the course of suing, I had to go through, like, years of accounting, and I found out that they were double dipping, where they were taking a 40% residual. And then on top of that, taking another 30% residual. So like, 70% of the marketing was being taken off the table before we shared in it. And of that 30% we split and got 15. I mean, it’s still a sizable chunk of money that we never expected to get. But it's probably 15% of what it actually ended up making. [Note: In a private bench trial, a retired judge acting as referee rejected most of Napoleon Productions' claims against Fox Searchlight, but according to The Hollywood Reporter, the court found “that Fox inadequately documented advertising expenses, and credited Napoleon with $125,357.”]

"Napoleon Dynamite" 10 Sweet Years Edition Blu-Ray/DVD Release And Statue Dedication

Napoleon Dynamite became a box-office smash — so much so that Fox unveiled a statue of the eponymous character on the studio lot in 2014. The Vote for Pedro t-shirt not only became the singular piece of merch associated with the film, but also became a cultural phenomenon outside of it too.

Jerusha Hess: We just celebrated the 20th anniversary at Sundance this year, and I've had to chat nonstop with a million people. And what I kept hearing was, “I know Napoleon. I grew up with Napoleon. I am Napoleon. I was Napoleon’s bully.” This is what they said, over and over again again. And I’m like, “Yeah, you're right.” Everyone has some tie to this type of person.

Sloss: Some of the best stuff I've ever worked on was a sort of a social critique, but also very…what’s the word I’m looking for? Not sentimental, but loving. There was something that you recognized in these characters. They're exaggerated, but they're also very affectionate.

Duff: I feel like we all can relate to those characters throughout high school. And seeing them come out on top? That’s what we all hope for.

Jerusha Hess: At the heart of it is the underdog winning, which is so satisfying to see. Culturally, we've just become much more politically aware as people, as news becomes more available. That’s where I think it's because this younger generation has said, “Yeah, I like this.” Because voting really matters to them. When I was friggin’ 18, I was not thinking about voting. It was not something on my radar. But today's kiddos are so much more socially minded. I think it's a very cool thing that that shirt took off.

In today's culture, it's really lovely to think about voting people in that wouldn't have a chance to. So I think it just still matters to vote for the underdog. And that is what that shirt means — that we're going to vote for someone who wasn't going to be voted for.

Avery: It shifted the minds of people without them even thinking deeply politically. They just love the movie and love the t-shirt, and the t-shirt has so many messages within that because of Pedro. And voting. It's also educating people about the necessity of voting. It's such a subliminal message. So when you see it, you love it for what it is. But you also are telling me who you are by wearing it.

Dekel: There's something about a fan buying a t-shirt and wearing that t-shirt when they put it on their body, and walk out into the world and engage others with a t-shirt that says Vote for Pedro, or Led Zeppelin, or fill in the blank. And it's also a form of social currency. Because when you are at the line at Starbucks, or you're waiting for the bus, and you look across and you see somebody with a t-shirt that means something to you, it more often than not will stimulate a response, sometimes a conversation. And so when you leave an interaction like that, where somebody says, “Hey, great shirt. Oh, I love that movie.” That creates a sense of connection, but it's also a sense of pride. It's also a sense of validation. It's led to friendships. It’s led to marriages. And so the humble t-shirt is, for me, much more.

Ramirez: Rather than having to look cool, it was saying: “It’s okay to be different. It's okay to be creative.” It's okay to not look perfect. When I think about that t-shirt, it symbolizes self-sacrifice for the wellness of somebody else. It symbolizes friendship.

Levitt: I felt like it was just this blowing up of this nerd culture that was maybe not as celebrated then, and I felt like that was part of it. You could just be geeky. Who cares if you weren't wearing your hair like this and tight jeans? You could just be dorky.

Napoleon flash mob

Bader: It was cool to wear a Vote for Pedro t-shirt. It’s fun if you had a Star Wars lunchbox, but Vote for Pedro t-shirt was like, cool, outsider, goofy. What's great about it is that it's both cool and nerdy simultaneously, right? That's a very difficult thing to pull off, that you're both dorky and cool. That you can be ironic and unironic simultaneously is a high-wire act.

It's really nice that this story is about the breaking of a monoculture…and I think that's what nerd culture really embraces. When I say nerd culture, I don't mean that in a pejorative way. I mean that as like, people that have interests and are allowed to pursue them.

Jerusha Hess: I'm pretty sure the Smithsonian reached out 10 years ago and was begging for [the original shirt.]

Heder: I had the [original] Vote for Pedro shirt. I kept that. I worked on another movie, School for Scoundrels. The prop master for that film, he liked to trade props…he would have props from other films he worked on or other actors he traded with. So he's like, “You got anything from Napoleon? That would be cool.” I was like, “Well, I got the original Vote for Pedro shirt. What do you got?” He was like, “Well, I do have one of the two Golden Snitches from the first Harry Potter movie.” And I was like, “Oooh.” I traded the Vote for Pedro shirt for a Golden Snitch.

I also remember thinking, “I mean, it's the Vote for Pedro shirt. They sell these all over the place!”

Lorenzen: The thing we tried to do with Napoleon Dynamite was to try to make it feel timeless. And not timeless like it's a classically beautiful thing, but timeless in that you can't place when this film necessarily takes place. We always viewed it, while we were making it, as a contemporary film, but in a land that might not have progressed as quickly or as fast as the world around it did. Even today you could still find homes and have wood paneling on the inside, and then have shag carpet here and there. So we were really looking for those things that felt like they had just been there for a while.

I grew up in LA, in Van Nuys. All the auto shops had that [Cooper Black] font. It's a very ubiquitous thing, and so it's also very familiar and comforting because of that. So when you see it in contrast by itself on the shirt, I think it really strikes you and feels comfortable, it feels good, and feels right. It doesn't feel like it's a forced new digital design, or anything that's trendy or of the moment. It really felt like it's something that’s been with us all along.

Originally Appeared on GQ