The novel 'Old King' explores the meaning of 'Unabomber' Ted Kaczynski today

When Ted Kaczynski killed himself in a federal prison last June, it closed a confounding chapter in the history of American domestic terrorism. Unlike fascists, white supremacists and antigovernment conspiracists, Kacyzinski espoused righteous principles: protecting the environment and facing the destructive role of technology. “[T]hreats to the modern individual tend to be MAN-MADE,” he wrote in a 35,000-word manifesto that ran in the New York Times and Washington Post in 1995. “They are not the result of chance but are IMPOSED on him by other persons whose decisions he, as an individual, is unable to influence.”

He wasn’t wrong. But the papers only published his words on the recommendation of the FBI and U.S. attorney general to prevent him from doing more harm — beyond the three people he’d murdered and nearly two dozen he’d injured with mail bombs.

Maxim Loskutoff’s second novel, “Old King,” is an attempt to sort through Kaczynski's contradictions, to acknowledge the manifesto’s prophetic elements while stressing it’s the product of a sociopath. That’s fine fodder for a novel — the stuff of Dostoyevsky, even — though Loskutoff isn’t trying to deliver a “Karamazov”-grade philosophical tale. Rather, “Old King” is a more modest blend of police procedural and great-outdoors yarn.

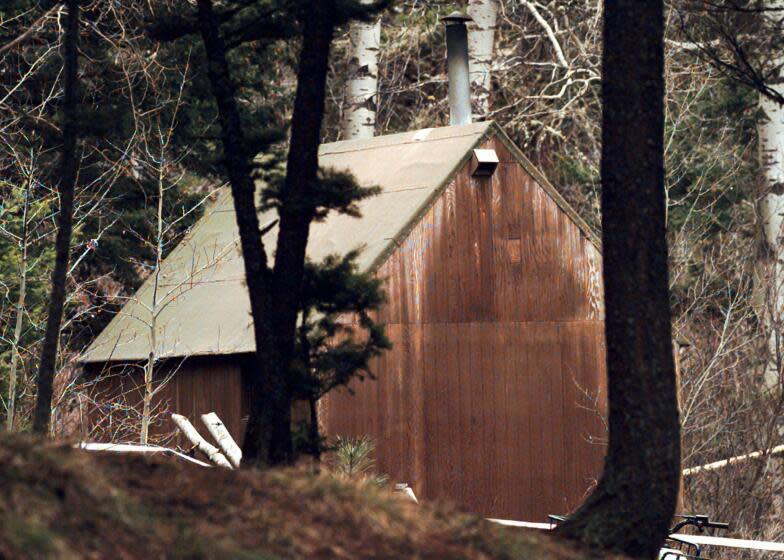

Set largely in the Montana wilderness where Kaczynski holed up, the novel explores the line where independence becomes so distant from empathy that it’s toxic. Loskutoff writes beautifully about nature — “Old King” refers to a massive tree towering over the Montana landscape. But nature on its own, he observes, can be menacing and brain-scrambling as well.

Before Kaczynski claims the novel’s stage, Loskutoff introduces a set of characters who evoke his crisis in miniature. In 1976, Duane is a young father who has just left his marriage and home in Utah to move to Lincoln, Mont., for work. He’s not especially skilled, and nature alienates him at first. (“Branches rustled, reaching toward him, offering up his failures.”) But he soon lands a logging job and gets to know the locals: Mason, a forest ranger; Hutch, owner of an ad hoc animal rescue; the Carter family, a clan of cranky separatists; and Jackie, Mason’s ex and a diner waitress. Settling in, Duane gifts Jackie with a microwave he liberated from his broken marriage, a small symbol of both warm domesticity and cold technology.

Indeed, it’s likely no other microwave in the history of American literature has been asked to carry so much metaphorical weight. Even without dwelling on the device, it’s clear that everybody in the area is trying to figure out to what degree they can balance the wilderness’ capacities for wonder and alienation. Mason, the ranger, is the most sophisticated thinker on the matter, questioning whether his job is preserving the environment or helping to accelerate a land rush: “By arresting poachers and running old trappers out of business, he’d clear the way for rich tourists to build second homes… Their contracting crews killed animals by the score with bulldozers, and the cement they poured left no way for the trees to grow back.”

As the narrative moves into the ’80s, Mason is increasingly troubled by the irony of his work. Duane, meanwhile, acknowledges the healthy fear the environment puts in him: Seeing a grizzly, he falls into a “wild, plunging panic, as if he’d come here to be eaten, having finally crossed the line between civilization and his dreams.” Both responses qualify as a kind of wilderness intelligence. By contrast, Kaczynski, a brilliant mathematician before becoming the Unabomber, is rendered as a more crazed, lunkheaded type: “The bear was the first real killer he’d ever encountered. He wanted to be a killer.”

There’s an unwritten law that literary fiction set in the high plains be sturdy and simple — sentences firm as fence posts, commas hammered in as clean as barn nails. Kent Haruf’s novels are the exemplar of the form, but the sensibility runs through books by Thomas McGuane, Marilynne Robinson, Peter Heller, Ivan Doig and more. Loskutoff, who set both his novel “Ruthie Fear” and story collection “Come West and See” at least partly in Montana, has mastered his own take on the form. He deftly captures how the environment is both enchanting and fearsome, and though his set pieces have a familiar ring — bar fights! dangerous animals! — he focuses more on what’s troubling his characters than overselling some myth of rough-and-ready swagger.

Read more: Weaving the personal and the political during the tumultuous 1970s

Still, the plainspoken approach means some characters lack depth. Jackie, the waitress, rarely rises above the trope of the straight-talking done-wrong Western woman who can’t find a good man. The trouble is more acute in Kaczynski’s case. Luskatoff introduces a postal inspector, Nep, who’s trying to chase down the Unabomber and grasps the threat he poses to America’s sense of self, then and now. (“Race riots, serial killers, assassinations, superfund sites. The great ship of America going down with all the lights blazing.”) But Nep is basically a stock detective, and Kaczynski little more than an angry narcissist who derides everyone around him as fools. His contempt for humanity is clear. But then why was he concerned for it?

For Loskutoff’s purposes, Kaczynski serves less as a character than a warning. The Unabomber was more than a ’90s headline; his past is closer to our present than we think. When a Montana local tells Mason about a brutal act of violence that happened in the ’20s, Mason brushes it off: “That was fifty years ago.” The man scoffs: “You think that’s a long time?”

Mark Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Get the latest book news, events and more in your inbox every Saturday.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.