How one grisly crash prompted a Kansas City suburb to change its police chase policy

Nearly 20 years ago, Ryan Sharp woke up to news reports of a Grandview police chase and a serious crash on the other side of the state line.

Two teenage girls had been struck by a cruiser traveling at 81 mph following a lengthy pursuit that ended at 119th Street and Nall Avenue in Leawood. The front-seat passenger, a 16-year-old, nearly died after suffering severe injuries, including a shattered pelvis and ruptured internal organs.

“I knew immediately that our chase policy was going to change,” said Sharp, now the captain overseeing patrol for the Grandview Police Department.

He was right. The 2004 crash led to a major shift in the way Grandview, a community of 25,000, handles police chases today.

After the wreck, Johnson County prosecutors took the rare step of filing misdemeanor charges against the two Grandview police officers — Brian Blessing and Doug Blodgett — involved in the pursuit. A $3 million civil settlement also followed.

The two officers, driving separate squad cars, had been dispatched to help Belton police with a car that had been reported stolen. The chase started when a car matching the description, spotted by Blodgett, fled a traffic stop with its headlights off.

Officers continued to chase because they believed a woman inside the car might’ve been abducted, according to a police affidavit filed in Jackson County Circuit Court.

The crash kickstarted a conversation among area policing leaders about bringing pursuit policies into closer alignment, though agencies continue to employ various practices around the Kansas City metro. Many agencies allow officers to chase at high-speed for any infraction, no matter how minor.

For its part, Grandview did change its policy. Officers are directed to only pursue offenders believed to have committed a violent felony crime. That’s a restriction recommended by many national law enforcement experts concerned with the risk police chases pose to public safety.

“There’s definitely a lot more that goes into even the initiation of a pursuit and definitely a lot more continual reevaluation during the pursuit of if it’s worth it to keep going,” Sharp said. “Back in the day, you would chase until the wheels fell off.”

Sharp stressed that he does not believe other agencies with looser policies are incorrect. But, overall, he says the current policy in Grandview has been beneficial from a public safety standpoint where pursuits are concerned.

“I think for the safety aspects to the public, I mean, if you’re not chasing cars, then you’re not pushing them into intersections … that people aren’t expecting a car to be flying through. So it’s certainly safer.”

Police chase policies across the metro

Many policing experts advocate for policies that limit police pursuits to situations where a suspect is believed to have committed a violent felony and the offender poses an imminent threat to public safety.

In many cases, police pursuits end in serious wrecks, sometimes injuring the suspects, innocent bystanders or the police officers themselves.

As part of a monthslong investigation of police chases across the Kansas City area, The Star examined the policies of 77 metro police agencies on both sides of the state line. Twenty-one departments were identified as having a chase policy in which police officers only pursue those suspected of committing violent felony crimes.

In the Kansas City metro, police departments at the other end of the spectrum continue to allow for pursuits in most circumstances.

Twenty-eight — including Independence, Gladstone and Raytown — have broad parameters, allowing officers to chase for almost any offense, that many policing experts say often create public safety risks that outweigh the benefits of an arrest.

Grandview, with a department of 55 sworn officers, is among those with a stricter policy that advises officers to chase only in situations where a suspect is wanted for a violent felony offense.

Under Grandview’s current pursuit policy, officers are instructed to chase suspects who have committed or attempted to commit a violent felony such as murder, sexual assault, arson, kidnapping or a terrorist act. Still, officers are advised not to pursue “when the danger to the officer or the public outweighs the need to apprehend the violator.”

Pursuits of traffic violators, including those suspected of driving under the influence, are explicitly prohibited. The policy also advises officers and supervisors of a responsibility to closely monitor progress and weigh the need to apprehend “against the potential danger created by the pursuit.”

John Hamilton, a professor emeritus at Park University in Parkville and a retired Kansas City police major who oversaw patrol in the Northland until 2003, said the policy Grandview employs is a restrictive one similar to Kansas City’s.

Specifically, Hamilton said, the policy has similar safeguards restricting pursuits to more serious offenses, continued evaluation and supervision of pursuits and a clear direction for commanders to have officers call off chases when appropriate.

Grandview Police Department pursuit policy by Ian Cummings on Scribd

Hamilton said many officers on patrol, especially earlier in their careers, become emotionally invested when someone flees and they start a chase. Among the benefits Hamilton cited in Grandview’s policy is the presence of a supervisor to ask questions in real time — the potential risks, rewards — and make a decision on whether to pursue.

“As these things go, the emotion starts to grow. There’s a lot of things going on at the same time. And you know, when judgments are made by emotion, most of the time rationality goes out the back door,” Hamilton said. “… And so it’s very difficult sometimes for an officer who starts these things to say, ‘Hey, forget this noise,’ and shut everything down.”

Five years, 35 pursuits

Of Grandview’s 35 pursuits over the past five years, 25 were initiated based on a suspected felony offense, including cases of armed carjackings, aggravated domestic assaults and a sighting of a person believed to have been wanted in a homicide.

Twelve ended with some type of crash, ranging from a suspect vehicle striking a curb to a police vehicle being struck by a fleeing driver.

Six began as misdemeanor traffic offenses.

In all, eight pursuits were found to have violated department policy. Police records reviewed by The Star cited one case in which an officer was disciplined.

In one, which was determined to be a violation of department policy, an officer attempted to pull over a Jeep Grand Cherokee in February 2021 for unspecified misdemeanor traffic violations.

The officer chased the Jeep on Interstate 49, reaching approximately 85 miles per hour, and self-terminated the pursuit after exiting the highway on 163rd Street. But the officer continued to follow the driver, from a distance, until the vehicle stopped again in a merge lane for Missouri Highway 58.

The officer pulled up and turned the lights and sirens on and the fleeing driver took off, again, onto Highway 58. The driver struck a bystander vehicle and took off and the Grandview officer called off the pursuit. The driver was later arrested.

In assessing the officer’s conduct, a police sergeant wrote that the officer should never have pursued the vehicle in the first place and violated department policy by pursuing someone who “did not commit a qualifying offense.”

Another four pursuits were categorized as “Other,” such as a case where officers chased a vehicle seen leaving a known narcotics location. That chase ended inside of one minute after the suspect crashed into a parked car; a supervisor for the officers determined the department’s pursuit policy was not followed.

No bystanders or police officers were reported injured in cases reviewed by The Star. Minor injuries were recorded for two suspects.

Other departments change policy

While police chases of any length are far fewer than they were in Grandview 20 years ago, Sharp says there are possibly some drawbacks.

He says drivers appear emboldened to simply run from police to avoid penalties. And many police view that as a consequence where criminals may be escaping justice — at least temporarily.

“It’s kind of a double-edged sword that way,” he said.

The Police Executive Research Forum, or PERF, a nonprofit that researches police practices and offers policy recommendations, advises in its most recent guidance for law enforcement agencies published this year that pursuits only occur when two criteria are met: A violent crime has been committed and the suspect poses an imminent threat to commit another violent crime.

Absent those conditions, police should seek an alternative way to meet the goal of arresting the suspect, the advisory group says.

Other police departments have adopted more stringent rules for officers in the wake of bad wrecks.

In June 2021, a Lone Jack police officer spotted a speeding red pickup truck on a stretch of U.S. Highway 50. The officer chased the truck, in Friday afternoon traffic, and ran the plate to find the truck was stolen.

The chase continued at a high speed, as the suspect weaved through traffic and went into a grassy median along the divided highway. He ultimately went into the opposite lanes of traffic and crashed head-on with another vehicle.

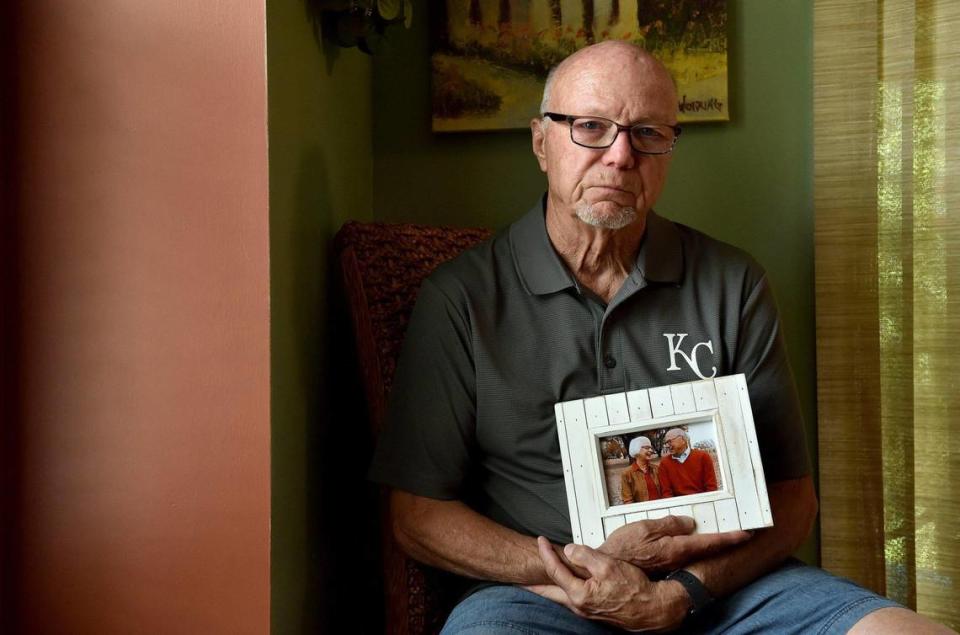

Patsy Arnold, 73, of Smithville, was killed in the crash. Her husband, Bob Arnold, a retired Kansas City police detective, has criticized the way police handled that chase. The fleeing suspect, a 33-year-old man, is charged in Jackson County with felony murder in her death.

At the time of the crash, the Lone Jack Police Department was operating under a pursuit policy that had been in place since 2005. It advised officers to beware of traffic and weather conditions, and drive with regard for the safety of others. But the policy broadly allowed for an officer to pursue if one “reasonably” believed a fleeing suspect “would present a danger to human life or cause serious injury.”

Since the crash, the Lone Jack Police Department has instituted a far stricter pursuit policy. The change came after the small town paid out a settlement to the Arnold family of $441,000, which amounted to the maximum civil award allowable under Missouri law.

Officers in Lone Jack are now instructed to “only initiate pursuits for violent felonies” under current policy.

Lone Jack Police Chief Tim Cosner, who took the helm after the 2021 crash, declined to be interviewed about why the department’s policy changed.

Officer from 2004 crash works for Independence

The two Grandview officers involved in the 2004 chase stopped working as police officers in the period immediately after the crash — a condition Johnson County prosecutors at the time sought by bringing misdemeanor reckless driving charges.

Blessing, whose cruiser struck the teenagers in Leawood, went through a diversion agreement and Blodgett, in the lead cruiser following the stolen car, was found guilty through a plea agreement. Blodgett was sentenced to six months of probation and 50 hours of community service.

Blodgett was later hired by the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office and then as an officer for Independence police, where he continues to work.

The Independence Police Department has by far the most police chases and crashes of any agency in the Kansas City area, The Star’s investigation found.

During an interview with The Star, Independence Police Chief Adam Dustman said Blodgett’s history was taken into consideration when he applied for his job and was hired.

“That officer’s had a long-standing career in law enforcement. And you know, none of us are perfect. Obviously, we make mistakes. We try to improve where we make mistakes. We learn from them and we rectify those mistakes the best we can,” Dustman said.

“He is still employed with the Independence, Missouri, Police Department and he’s doing a good job.”

How we reported this

After two innocent bystanders were killed in a police chase in March in Independence, Star reporters began looking into law enforcement pursuits in the Kansas City area. Over the next nine months, the reporters filed more than 140 public records requests with more than 60 local law enforcement agencies across the metro. They gathered police pursuit policies and documents recording chases, crashes and injuries over a period of five years.

Reporters also obtained investigative case files from serious and fatal wrecks, including dashboard camera recordings. They reviewed court documents from lawsuits and legal settlements. In all, the team examined more than 4,500 pages of documents, allowing them to identify patterns in police pursuits and practices in the metro.

They also spoke with more than 60 people, including innocent bystanders who were injured in police chases, families of victims killed in pursuits, police officials, attorneys and academics who have been studying the topic for decades. They interviewed a person in prison serving a sentence for killing four people in a crash during a police chase in 2018.

The project is published in a series of eight stories, with videos of interviews and crashes, as well as infographics showing the scope of police pursuits in the metro.

Credits

Katie Moore, Glenn E. Rice and Bill Lukitsch | Reporters

Emily Curiel and Nick Wagner | Visuals

Monty Davis | Video Editing

Neil Nakahodo | Illustrations & Design

David Newcomb | Development & Design