One of Them by Michael Cashman review – from Albert Square to Parliament Square

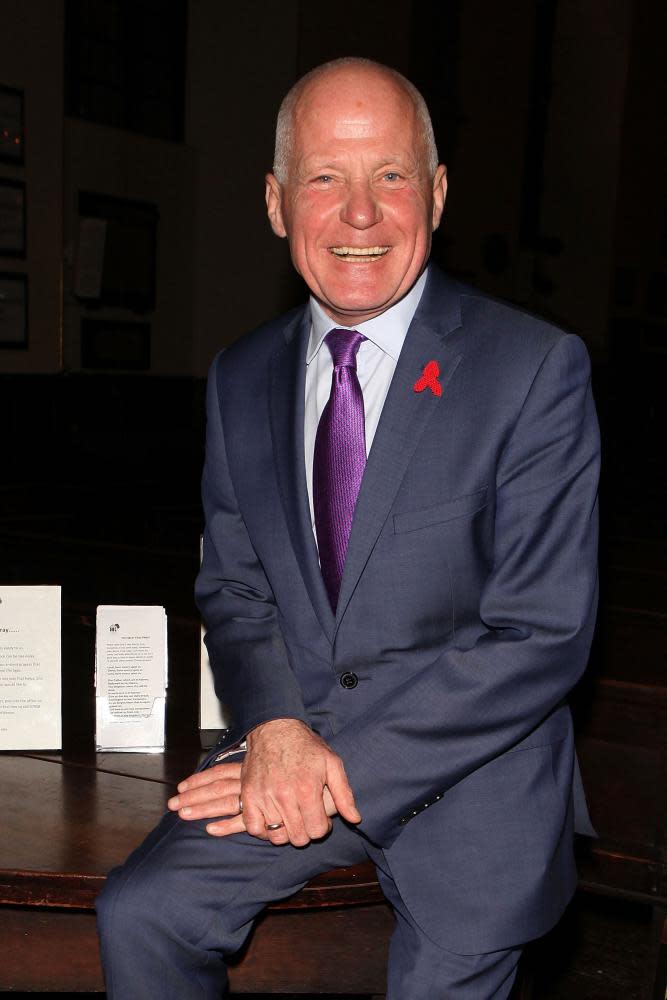

We know Michael Cashman, or we think we do: the charmingly fresh-faced, somehow ageless actor who played Colin in EastEnders, was involved in the first gay kiss in a soap opera, became a gay activist then an MEP, and is now a member of the House of Lords. The title of his memoir tells us that his sexuality is central to his identity, and it is true that he has been absolutely fearless in proclaiming it – a particularly brave thing in the late 1980s, and he suffered the scabrous abuse of the tabloid press for it: “EastBenders!” the headlines howled. The News of the World led with “Secret Gay Love of Aids Scare EastEnder”, associating a storyline from the show with Cashman himself.

The paper also published his address, which resulted in bricks being thrown through his window. The Sunday Mirror managed to surpass this, confronting him on the doorstep with the claim that he had just come back from the US (he hadn’t) where he had taken an Aids test (he hadn’t), was almost certainly dying of it (he was clearly in radiant good health) and had decided to break off his relationship. He told them to tell his partner, Paul Cottingham, this. They already had, they said, but they didn’t mean him, they meant another lover with whom he was allegedly passionately involved.

He finds solace in the pre-1967 gay West End, of which he offers a masterly evocation in all its gaudy glory and horror

All this was before the notorious kiss between Colin and his working-class lover, Barrie. Now the rags were apoplectic. “Filth”, proclaimed the Daily Star: “Get this off our TV now.” Tory politicians weighed in: “If the BBC can’t stop showing these perverted practices during family viewing time, then EastEnders should be banned or scrapped altogether.” The BBC stood by the series: the fundamental change in British attitudes to homosexuality over the last few decades owes something to the programme and to Cashman.

One of Them reveals a great many other Cashmans you might not know about: the child star, playing the lead role in Oliver! in the West End; the would-be doctor, giving up his successful TV career for a year at a crammer trying to din into his unresponsive skull the elusive science qualifications he needed to apply to medical school. Then there’s Cashman the playwright, protege of Alan Ayckbourn, taken up by the agent Peggy Ramsay; two of his plays were successfully performed at the prestigious theatre in Scarborough. After EastEnders, he became a spokesman for gay causes; he was often paired with Ian McKellen (“Shakespeare and Soap”) on anti-Section 28 platforms. Eventually he became involved in politics, as a dedicated and highly effective MEP. He quit, but almost immediately was in the House of Lords. After therapy, he discovered that he had an addictive personality. I think we could have told him that.

His first-hand testimony is illuminating, bright and breezy, lightly scattered with exclamation marks, fairly relaxed about grammar. But it is not the heart of the book. That is to be found at either end of it, when, in the first 100 pages, he writes about his East End childhood through the eyes of his own young self, then again in the last 100 pages, when he tells of the illness and death of Paul from the point of view of an anguished onlooker. In both of these long sections, perhaps because he is at the mercy of events and not driving them, he allows himself a level of emotional recall that crystalises and distills experience into unforgettable images.

“St Vincent’s in Limehouse was a newly built estate … it accommodated around 2,000 of us, all shapes, all sizes, and Josie the prostitute. In our block lived the Kamaras, the only black family on the estate and there was someone we called the “China” man. Another of our neighbours, Mrs Cootes, had lost the use of her legs and travelled around on what looked like a lay-on-your-back bicycle that she pedalled with her hand.” These pages are in the league of My Early Years, Charlie Chaplin’s great account of late 19th‑century south London – graphic, filled with smells and tastes and strange encounters. One evening he is accosted by a man asking him if he wants to earn a shilling. It is his first, furtive, frightening experience of sex: “He told me to stay where I was, that I was to be good, then pointed his finger at me and said he knew where I lived. I nodded and just kept nodding and trying not to cry. And I wished I’d never wanted that fucking shilling.”

Increasingly Cashman realises that he’s “different”, overhearing his mum tell his Aunty Eileen: “I think he’s one of them.” His talent as an actor brings him respect at school and then he’s spotted and given the job in Oliver!. At the stage door one night, he’s taken up by a man who undertakes to look after him professionally; inevitably, he looks after him sexually, too, pretending to landladies that he’s his son. He’s just 15. Soon he finds a live-in lover, 20 years his elder, and another sort of a nightmare, but it’s passionate and true between them, until he has to break away, finding his solace in the pre-1967 gay West End, of which Cashman here offers a precise and masterly evocation, in all its gaudy glory and horror. “In the corner of every bar was an old queen, warning you what your future would be: ‘You’ll be old and no one will fucking want you either, dear’”.

At Ayckbourn’s theatre in Scarborough he meets Cottingham. One of Them becomes, from this point in its story, a celebration of their relationship. Cashman gives a vivid account of the fun they had in what was, from a very early stage, an open relationship – wide open. Foreign trips seem particularly rewarding in this regard, notably a trip to the Soviet Union, when virtually every grim-faced KGB man seems to want to jump into bed with them; it gives a whole new dimension to the phrase “orientation tour”.

Related: Section 28 protesters 30 years on: ‘We were arrested and put in a cell up by Big Ben’

All of this is vivaciously rattled through, but it takes a death – or rather two, those of his mother and then his father – to draw from Cashman significant and mediated detail. Suddenly, we’re seeing the world through his eyes again: we’re there. And it is heartbreaking. Soon he’s facing a series of shocking and ultimately terminal medical crises with Cottingham. “Now I was sat in the corner of the armchair. Watching. Waiting. Suddenly I flinched and I knew. I said to someone to get the others because he was going. I watched him take a deep breath. He breathed out. And breathed in no more. I rushed towards him. ‘Go, my darling. Go!’ I shouted.”

He finds among Paul’s papers the letter he wrote as a 19-year-old to Cashman after their first night. “I want to help you all I can, and so the best I can do is love you.” In passage after passage like this, Cashman has written a great book about love, pain and the whole damn thing.

• One of Them: from Albert Square to Parliament Square by Michael Cashman is published by Bloomsbury (RRP £18.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15.