An Ontario farm town will vote in October on whether it wants to house Canada's largest nuclear waste dump

A bucolic Ontario farm community will decide in an online vote this fall if it wants their quiet rural town to be the site of a multi-billion-dollar project — Canada's largest permanent tomb for millions of bundles of spent nuclear fuel.

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization's search for a deep geological repository stretches back decades, and has been narrowed down to:

Teeswater, a town with a population of about 5,880, 170 kilometres north of London and part of the municipality of South Bruce.

Ignace, a northwestern Ontario community with a population of about 1,200, some 245 kilometres northwest of Thunder Bay.

On Wednesday, Teeswater officials published the terms of the deal for voters to decide, in an online referendum on Oct. 28, if they'd be in favour of being home to the repository.

If the vote is "yes" to burying used Candu reactor fuel deep below the earth, the town will get hundreds of high-paying jobs and $418 million in subsidies from Canada's nuclear industry over the course of the project.

If voters say "no," the town still gets $4 million.

The referendum's outcome will only matter, of course, if Teeswater is chosen over Ignace — a decision the NWMO expects to announce by year's end. Earlier this year, the NWMO, which is tasked with finding storage for Canada's nuclear waste, reaffirmed its confidence in the project's safety.

Once the host site is chosen, there will be a regulatory decision-making process, followed by a construction period of about 10 years. The facility is expected to be operational in the early 2040s. The latest NWMO projection, in 2021, estimated the project would cost $26 billion over its 175-year life cycle.

Community divided over nuclear repository

For people in Teeswater, the October referendum would be the culmination of a 12-year debate that has left deep ruptures in the community, between those who see welcoming radioactive waste as a new kind of prosperity and those who see it as just a potential danger.

For instance, according to a March 2021 report from South Bruce's treasurer, the community had received more than $3.2 million from the NWMO since 2012, and the money has been used for everything from St. John Ambulance training, to offsetting extra costs of the pandemic and paying the salaries of municipal employees.

Those against the project have included a citizens' group, Protecting Our Waterways – No Nuclear Waste, which argues the NWMO's plan to bury the nuclear waste "is untested, unsustainable, and ... unwanted in our community."

"We are not anti-nuclear," the group's website says. "The nuclear industry provides many of our residents with well-paying jobs and is a positive contributor to our local economy. However, South Bruce has already done its part for the industry. Just because the NWMO likes our geology doesn't mean our community wants to store its nuclear waste underneath our geography."

The proposed 600-metre-deep geological repository would see spent nuclear waste contained behind multiple barriers, including copper casks, bentonite clay, layers of concrete and the geology itself to keep the waste sealed away.

"We know that system of protection does work and the challenges are not likely to ever occur that deep underground," said John Luxat, an engineering professor at Hamilton's McMaster University who holds the senior industrial research chair in nuclear safety analysis.

Luxat said the best way to ensure the waste remains sealed away is to keep it as far as possible from air and water, which will cause the copper containers to oxidize.

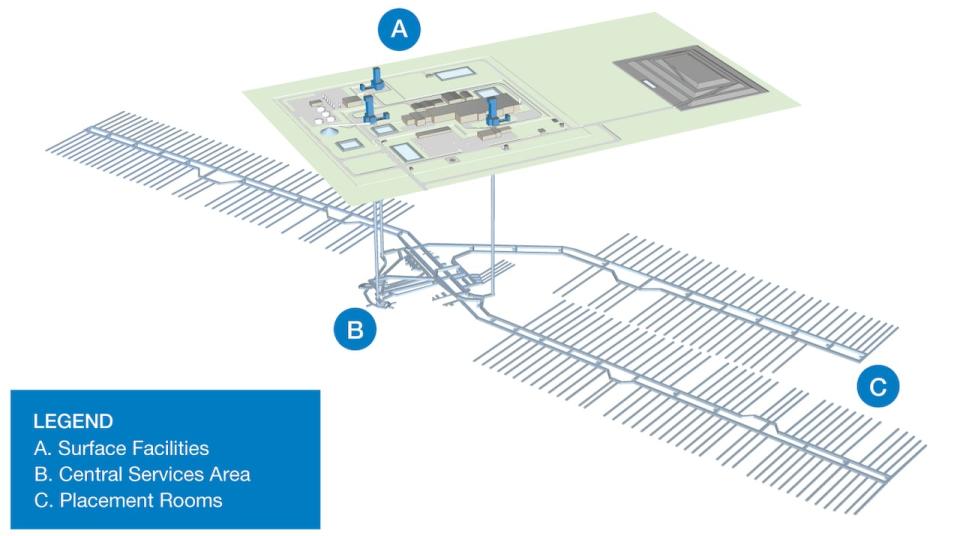

A diagram shows the vast underground network of chambers that would permanently hold spent nuclear fuel deep below the earth in a deep geological repository. (image supplied by the Nuclear Waste Management Organization)

The deep vault is nearly three times the 229-metre depth of nearby Lake Huron, far away from water. If penetrated, the layers of concrete and clay surrounding the waste could cause the copper casks that contain it to rust.

"You need to keep it away from air and water," Luxat said, adding the vault is "for all intents and purposes meant to store the waste forever."

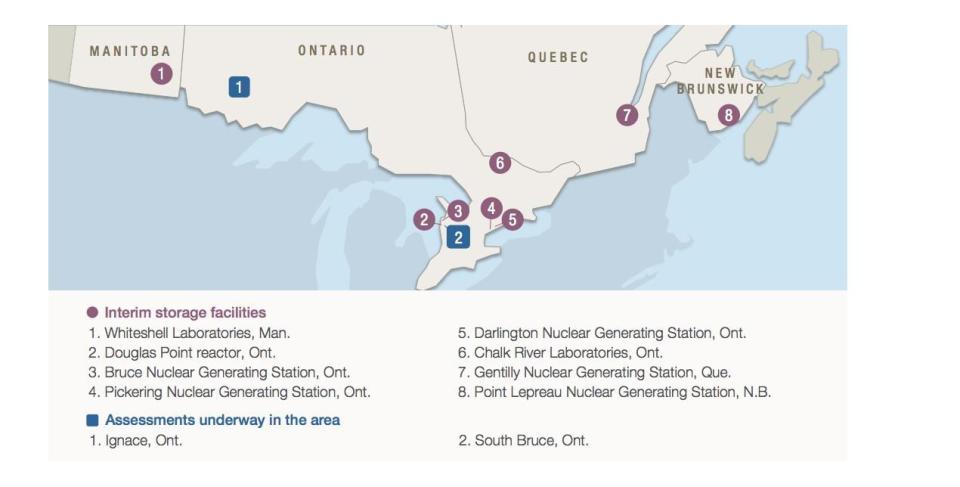

Once the repository is built, the NWMO said, some 30,000 shipments of nuclear waste would begin moving from eight interim storage facilities from Manitoba to New Brunswick to the Ontario dump site through some of Canada's most densely populated areas.

This map taken from the NWMO's proposed transportation plan shows the relative geographic position of interim storage sites and the two Ontario communities being considered to store Canada's nuclear waste. (NWMO)

Even then, Luxat said, the risk is minimal, noting the transportation of spent nuclear fuel already happens regularly. The rods are moved to cooling ponds where they would rest for approximately 10 years. After that, they're taken to temporary holding facilities, in either shallow pits or above ground in dense concrete bunkers.

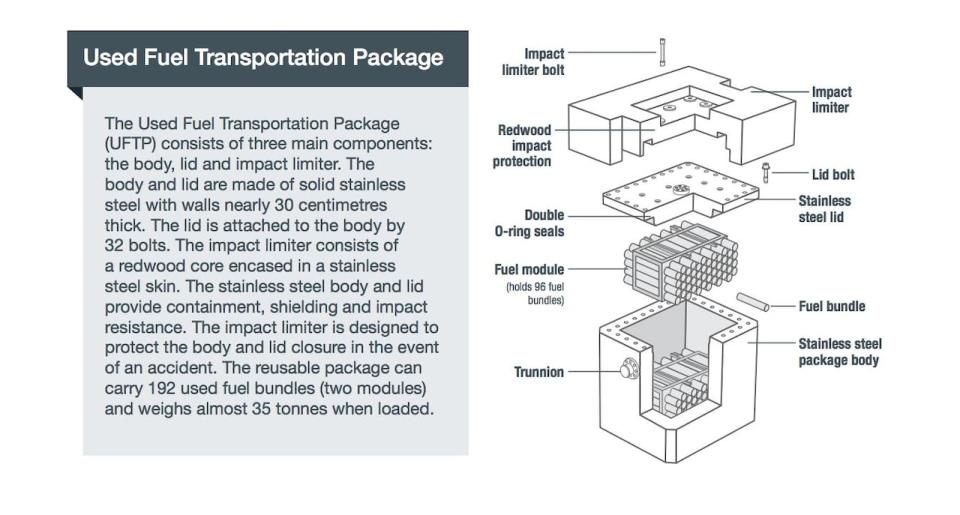

This image, taken from the NWMO's transportation plan, details the components of the containers in which spent nuclear fuel rods will be shipped. (image supplied by the NWMO)

Luxat noted that when nuclear waste is moved anywhere, it's packaged and sealed inside a specially designed container that could withstand collisions from large vehicles, such as trains, or being dropped from great heights.

"They've been doing this transporting the spent fuel to temporary sites for decades now and there's never been a

dangerous event."

In some cases, Canada's nuclear waste, has been sitting in temporary storage since the mid-1960s and Luxat said the risk of finding a permanent place to entomb it is far greater than leaving it where it is.

"It would be a significant increase in risk because they would be potentially exposed to much higher levels of moisture," he said, noting both Teeswater and Ignace were chosen because of the "low probability of seismic damage to the rocks."

Protecting Our Waterways - No Nuclear Waste is a grassroots group that's trying to stop the community of Teeswater from becoming a disposal site for Canada's nuclear waste. (Michelle Stein)

In order to make the deep geological repository a reality, the nuclear industry still needs the support of nearby Saugeen First Nation, which has yet to make a decision on the project.

When reached by CBC News on Wednesday, Chief Conrad Ritchie said he wouldn't comment until Saugeen's band council had a chance to meet with representatives from nearby Ojibway of the Nawash First Nation on the Bruce Peninsula later this week.