An open door to reconciliation: inside Ottawa's new Indigenous Peoples building

Inside the ornate former U.S. embassy across from the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, a set of plain tools sits in a glass display case — knives for cutting and scraping hides, a stone oil lamp.

The tools are carefully made by hand and appear new. In a sense, that's why they're here. In a city filled with museums offering carefully curated glimpses of Canada's past, 100 Wellington Street delivers something else — an encounter with the way Indigenous Peoples live and govern themselves now.

"I know the people who made these items. This isn't from the history pages," said Natan Obed, gesturing at the displays inside 100 Wellington Street's public spaces. He's president of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national representational organization of the Inuit.

"And that's a really important thing for us as well, because a lot of people still don't necessarily know that our society is still alive and thriving today."

Two decades after the Americans moved their diplomatic mission blocks away to that imposing steel and stone structure on Sussex Drive, 100 Wellington is getting a second life as an embassy for Indigenous organizations, providing office and conference space to the Assembly of First Nations, the Métis National Council and ITK.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau donated the space on the government's behalf on National Indigenous Day in 2017.

Obed's hope is that 100 Wellington Street will serve as symbol as much as structure — one that helps Canadians see the relationship between national Indigenous leaders and the federal government as one of equals.

"For First Nations, Inuit and Métis to be recognized as a part of the work that happens here on Parliament Hill and within the precinct, is a massive step forward in reconciliation," Obed said.

"What we make of it now is whether or not this idea can make it from a conceptual level to actual fruition."

Before now, there hadn't been a space within the Parliament Hill district dedicated to and for Indigenous people.

Indigenous leaders plan to use the new facility to host high-level meetings with prime ministers, cabinet ministers and other dignitaries.

A place at the centre of federal power

Right now, Indigenous leaders trying to get to meetings inside the Parliament Buildings need to pass through various checkpoints and airport-style security checks involving X-ray scans. While other dignitaries are fast-tracked by security, Obed said, Indigenous leaders can spend up to 30 minutes just trying to get inside.

Indigenous groups usually have to rely on sympathetic MPs and their staff to acquire space on Parliament Hill to hold meetings. If they can't get that help, they typically end up renting conference space in pricey hotels.

"[100 Wellington Street] allows for us to revisit the way in which Indigenous leadership is recognized and respected within [the] precinct, and not just access to this building," Obed said, adding he hopes the facility changes "the way Indigenous leadership, elected leaders on behalf of First Nations, Métis and Inuit rights holders, get treated when they come to Ottawa."

The building doesn't have an official name yet; it's being referred to as the Indigenous Peoples Space. Renovations are nearing completion on the first two floors.

Obed is pushing to open the main doors to the public as early as next month, but that decision also rests with the building's other tenants. Right now there's no word on when that grand opening might happen.

"I think the prime minister showed leadership in 2017 by announcing that this was going to be a space for First Nations, Inuit and Métis," Obed said.

"Now leadership is needed again to make it all happen, because this is not a small project."

Demonstration and delay

The building was supposed to open last summer, but those plans were upended after members of the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation blocked the main entrance and demonstrated outside on the sidewalk for 13 days demanding to become a fourth partner in the project.

"A partnership, of course, means to me title, recognition of the Algonquin people in the Ottawa area," said Verna Polson, the grand chief of the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council.

"For us, as a nation, we need that space as well, where we can have those dialogues with the government, with our partners who we are working within the Ottawa area, and to showcase our traditions."

The Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation represents Algonquin First Nations in Western Quebec and Eastern Ontario; they say the building at 100 Wellington Street stands on their unceded land.

The federal government reached an agreement with Polson after she staged a 41-hour hunger and hydration strike.

Under its deal with the federal government, the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation is getting an empty lot behind the former embassy to turn into a space where Polson and her leadership can hold meetings and showcase their culture.

But Polson is standing her ground over 100 Wellington Street, saying the building will not open before the other Indigenous organizations agree to make the Algonquin a partner until their own space opens.

"I'm still hopeful," Polson said. "We all want the same for our nations and our people."

Obed said he hopes the events of the past summer don't undermine the ultimate goal of the project.

"We're hoping that the Algonquin can work with us on finding that specific way to be respectful of their interests, but also be respectful of the entire initiative itself," Obed said.

Marc Leclair, senior adviser to the Métis National Council, said he is willing to meet with the Algonquin but wants the matter to be settled between the AFN and the Algonquin.

"The exhibits are completed and we're anxious to have it open to the public," Leclair said. "I hope that we can come to some resolution on that soon."

The AFN declined CBC's request for an interview, but sent a statement:

"The Indigenous Peoples Space will be an important place for all First Nations, Métis and Inuit leaders, governments and organizations to conduct intergovernmental business and strengthen relationships," wrote Perry Bellegarde, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

"Its presence directly across from the House of Commons, on the unceded territory of the Algonquin Nation, serves as an important reminder of our nation-to-nation, government-to-government relationship with Canada."

The building's interior is starting to take on its final form. The first floor is for visitors and is divided between the Inuit, Métis and First Nations, with displays showcasing their culture and governance models.

Upstairs is where business will take place. There's already a large wooden conference table set up on the second floor in a room lined with paintings by renowned Indigenous artists, including Christi Belcourt and Alex Janvier.

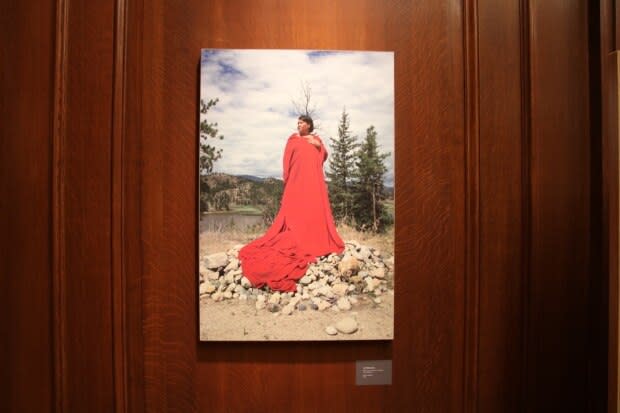

The neighbouring room houses a press gallery space for journalists. On its walls are photos of women standing in wilderness settings wearing bright red gowns — symbols of Indigenous women and girls who have been murdered or have gone missing in Canada.

The lobby, which is still under construction, eventually will feature a wooden sculpture depicting Ottawa's river system. The first floor display uses video to tell stories of traditional homelands.

"We're hoping people really get grounded when they come in here, even if it's just for ten minutes, in the lives of people within a specific place within Inuit Nunangat," Obed said.

"They'll be able to see a video about our homeland and be able to place it on a map as well. So we wanted to have an interactive space as well."

Largely because of its location — across the street from the Prime Minister' Office, directly in front of East, Centre and West Blocks — 100 Wellington Street is one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in the country right now.

Politicians have puzzled over what to do with the property since the U.S. embassy moved in 1999.

Including utilities and minor repairs, the building costs Public Services and Procurement Canada about $200,000 annually to operate and maintain.

Under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, the building was slated to become a portrait gallery. That plan was dropped when Stephen Harper came to power.

When he dedicated the building to national Indigenous organizations on June 21, 2017, Trudeau said those organizations should be the ones to decide how best to use it.

"Every single person who comes to this place will walk in front of a concrete reminder that at the heart of every decision we take in this place, we must remember our partnership and that the path forward goes hand-in-hand with the Indigenous Peoples of this land," he said.

"For the millions of Canadians who descended from settlers or who are newcomers yourselves, I say this: We hope that this place in the heart of our capital will serve as a permanent reminder that Indigenous Peoples are at the very heart of this great land."

Final costs of the building's renovations are still to be determined, said Crown-Indigenous Relations spokesperson Jane Deeks.

"This work is being undertaken in the true spirit of Reconciliation," Deeks said. "We are honoured to be a partner in this historic project."

Obed said he hopes the building will be fully functional in five to 10 years.

"This really opened the door figuratively and literally now for us to start having these conversations about Indigenous leadership working with parliamentarians, working in-precinct and having access to [the] precinct, because before there just wasn't an interest," Obed said.

"I think that it is time now in this country for that to just be a matter of course that there is a respect for Indigenous leadership, the same way there is respect for premiers of provinces or territories or members of Parliament or ministers. We don't have to be the same as [cabinet ministers]. We can create a special consideration for and a respectful relationship with the leaders of Inuit, Metis and First Nations."