We Opened an Abolitionist School. Then They Jailed One of Our Own.

Spencer Platt

We enter the summer of 2024 with Palestine on our minds and in our hearts — hearts that swell with admiration at the steadfastness of those resisting. Neither the struggle nor the repression with which it has been met are new. Like many, we were shocked at the images of riot police manhandling and arresting unarmed students. But for those of us observing the fourth anniversary of the 2020 uprisings — not to mention the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd that sparked them — such images are as familiar as they are unsurprising.

These four years have been short and long all at once: Time passing in fits and starts, marked by pandemic and lockdown, upsurge and downturn, breakout and struggle — punctuated by weeks in which decades happen, to borrow a phrase often apocryphally attributed to Lenin. Not everything is the same, however.

As students of history, we know that it rarely repeats, but it does occasionally rhyme. And more than that, it resonates, throwing forth new lessons, challenges, and missions — in the words of the influential anticolonial revolutionary Frantz Fanon — for new generations to either fulfill or betray.

Our project, the W.E.B. Du Bois Movement School, was the product of the 2020 rebellions, the wind in the sails of abolitionist organizers nationwide. The protests were a mass explosion against white supremacy nearly unmatched in US history — spreading faster and wider than even the riots that greeted MLK’s murder and the 1992 LA riots. The year 2020 shook the foundations of America’s racial capitalist order and reshaped the terrain of our struggles moving forward. While on one level this was simply another in a long line of struggles against police (and extrajudicial) killings in the US — from 2009 with Oscar Grant to 2012 with Trayvon Martin 2014 with Mike Brown to 2015 with Freddie Gray — each of these moments marked an escalation and elevation of consciousness and organizing.

Nowhere was this shifting consciousness more evident than in the question of police and prison abolition itself, which 2020 put on the agenda as never before. As Minneapolis organizer Kandace Montgomery put it at the height of the city’s struggle, “In 2015…we were clear about the problem. Now, we are clear about the solution.”

But for us, the mainstreaming of the language of abolition also posed difficult and challenging questions: What do we mean when we say abolition? And how do we make such a seemingly impossible goal a reality? How can we push back today on this repression and the ideas that underpin it? What is to be done when the smoke clears and the energy subsides?

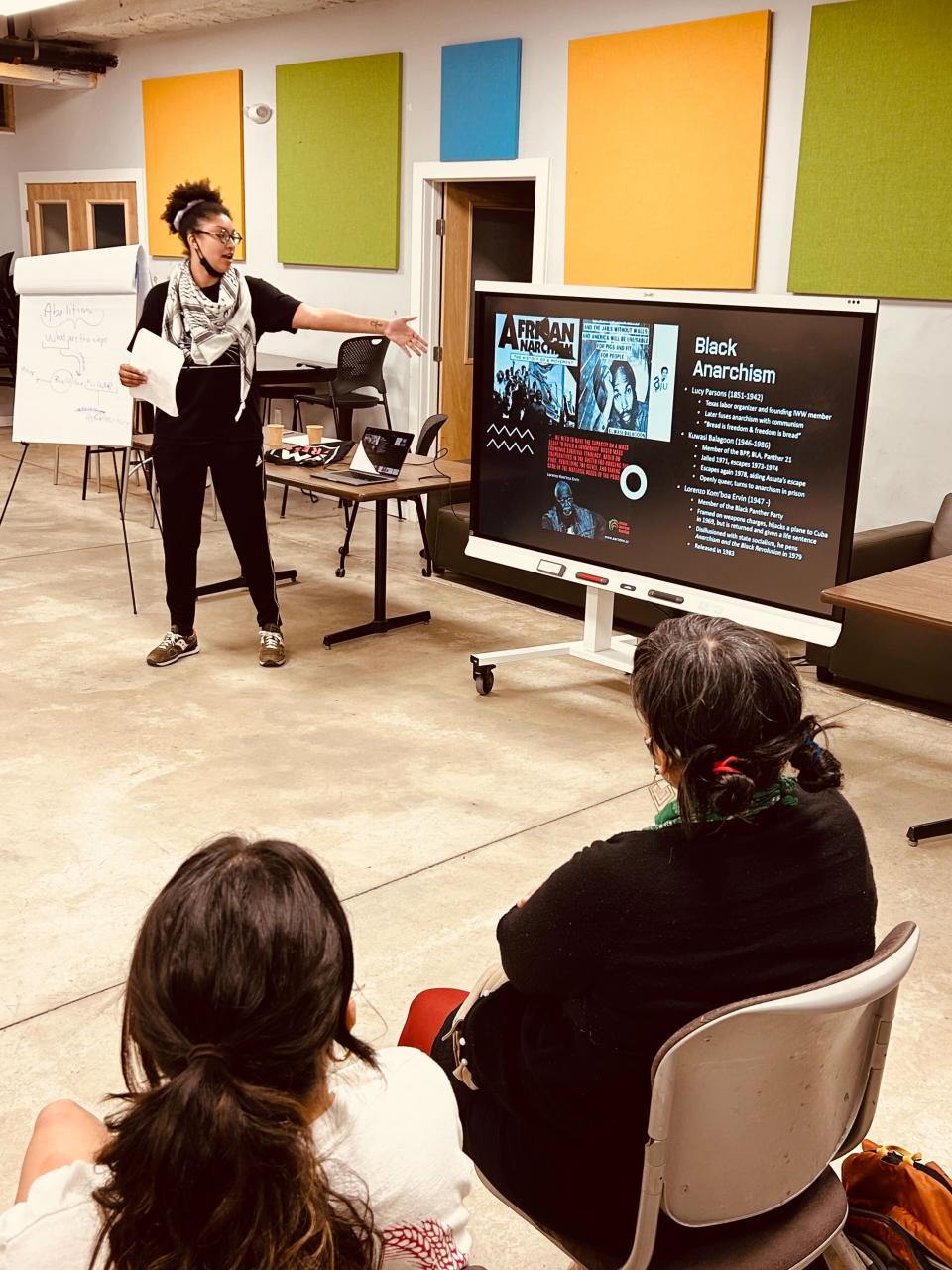

Moments of political upsurge inevitably give way to downturn and the question is what to do with those people — hundreds of thousands, in this case — who have been mobilized in such a short time. This is when political education and organization matter most. At the Du Bois Movement School, we do both, seeing education and organizing as a single urgent task for our political present. We grapple with essential questions of what abolition means by anchoring that understanding in a longer historical vision and a broader global scope. And we do so according to four basic principles: abolitionism, internationalism, intersectionality, and participatory education.

In 2020, many mainstream Democrats (though not Joe Biden) embraced the call to divert funding away from police and toward community programs. The mainstreaming of abolition wouldn’t last, of course. Instead of defunding or dismantling police forces, the four years since have been best characterized as a period of counterinsurgency — an effort to diminish the radical energy that exploded in 2020, to erase its victories and discredit our vision for a new and different world. A federal dragnet was deployed across the country, targeting participants in the 2020 protests. Authorities arrested, charged, and ultimately sentenced seven in Philly over allegedly being part of burning a cop car, a recurring image in the summer of 2020 for those following the protests.

For us, this repression hit close to home. One of those targeted was our own Du Bois Movement School facilitator Anthony “Ant” Smith, a gifted educator, born community organizer, and selfless human being. In October 2020, just two days after the police killing of Walter Wallace Jr., feds swooped in to arrest Ant. He was charged with obstructing law enforcement during a civil disorder for helping to flip a vacant cop car and for abetting arson by throwing a piece of paper on the vehicle once it was on fire. Last November, after years of house arrest, a federal judge cited Ant’s community organizing as informing his sentencing, saying his leadership “comes with a heavy price.” Ultimately, Ant was given a 12-month sentence — and with his felony conviction, a 10-year ban from working as a teacher. As we see it, Ant poses such a threat to the system that they had to take him away from us.

In Ant’s own words in an email from jail, targeting movement organizers is an effective way to wear down movements: “It surely worked to convict me as a felon, eliminate my career, and financially impact myself and my support system.” Cases like his cause for “focus to be redirected on supporting incarcerated community members rather than sustaining resistance and community-building efforts.” But while, he says, “the mainstream media has doubled down on fearmongering tactics” and elected officials continue to offer more of the same — “hyper surveillance, policing, and militarism” — the repression of the present isn’t invincible. “This country ensures that we are inflicted with the demons of isolation, individualism, and apathy, but through political education, community engagement, and sincere effort, we can overcome this latest wave of counterinsurgency and ignite the spirit of resistance once again.”

The forces that enact repression have had some undeniable success: the unseating of Chesa Boudin, San Francisco’s progressive DA, electing the former cop Eric Adams mayor of New York, and giving us our own Eric Adams here in Philly in Cherelle Parker. On the campaign trail, Parker promised a return to stop-and-frisk and even threatened to send the National Guard into the city’s struggling Kensington neighborhood. In power, she has stayed true to many of these reactionary proposals, delivering a massive increase in police funding, criminalizing mutual aid work for the city’s poorest, and unleashing a brutal sweep in Kensington — attempting yet again to solve social problems with police violence.

As internationalists, we believe that our struggles are intertwined with the struggles of Palestinians and recognize that domestic policing and imperial militarism abroad are not distinct phenomena, but part of a global system. When we say “Free ’Em All,” that means Palestine too.

Our job is to study both force and ideas and to develop and sharpen our own in this moment of renewed struggle around Palestinian liberation. Our job is to harness and stabilize the energy of explosive moments of struggle, to smooth the peaks and valleys of historical movement by building the consciousness and connections necessary for the next explosion. Our job is to ask hard questions about what abolition means and sharpen our collective analysis in the process. Our job is to push back on the copaganda and lies of the right by providing true explanations to the community about what is causing the violence that has racked the city since 2020. Our task is to study and understand, to struggle and fight for liberation on a worldwide scale.

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue

More great activism coverage from Teen Vogue: