He owes thousands in taxes. He’s got a controversial past. Why is Steve Garvey running for Senate?

To understand why Steve Garvey suddenly emerged as a political force and became the quixotic Republican hope for a U.S. Senate seat in Democratic California, just ask Tony Strickland.

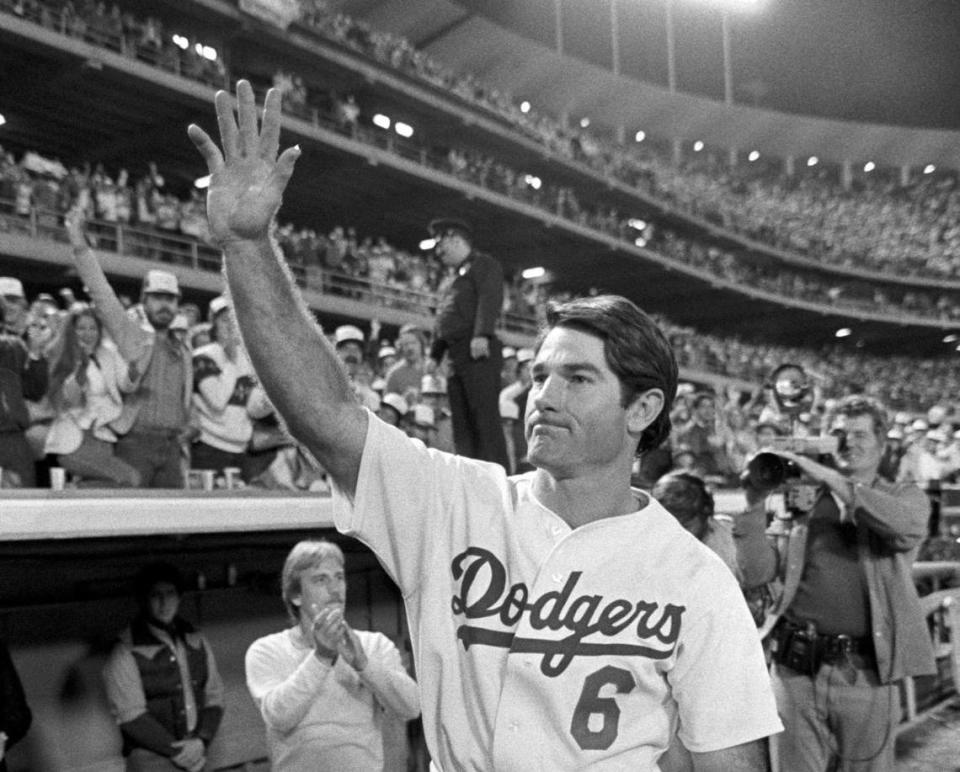

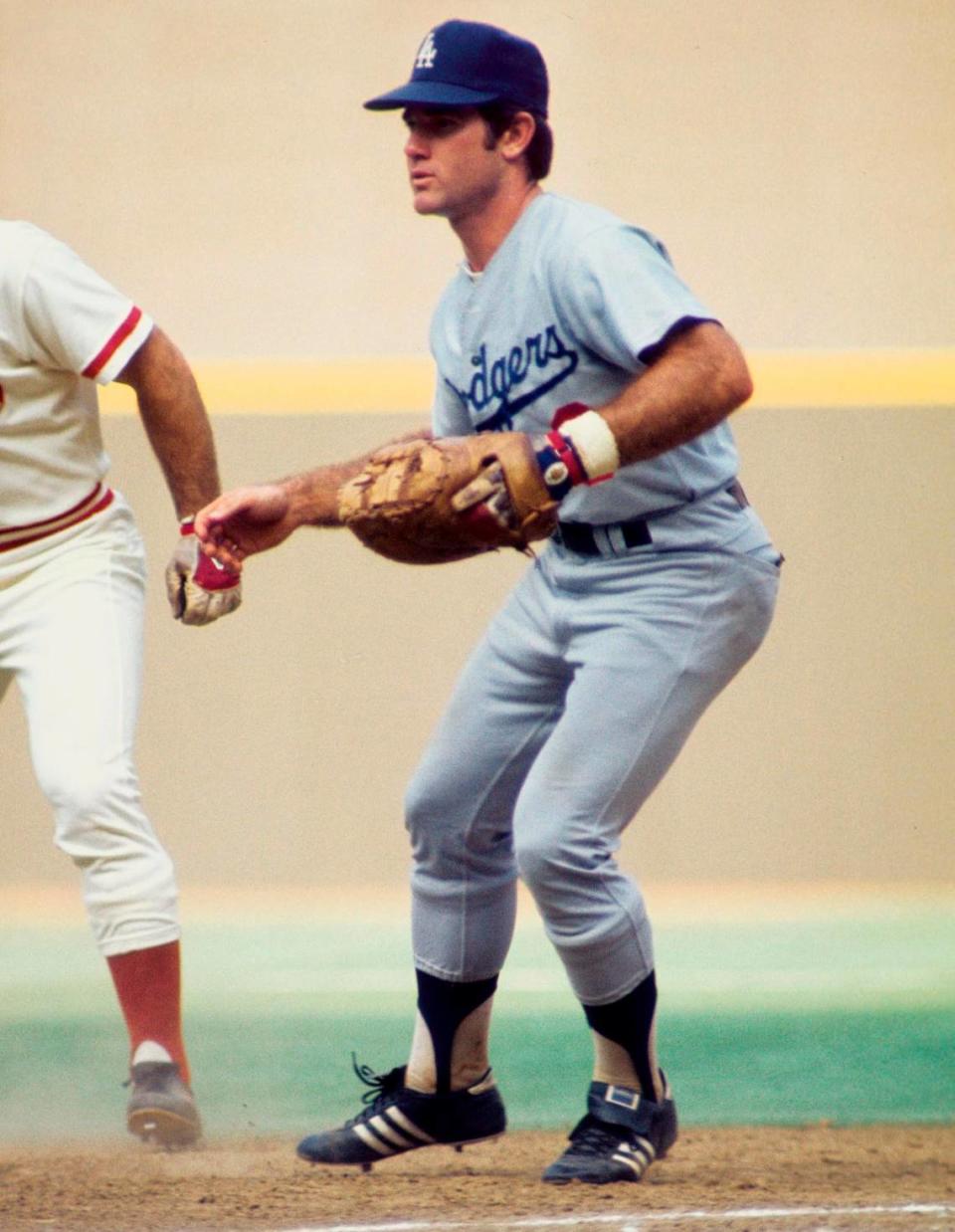

Now a Huntington Beach City Councilman, Strickland had a Steve Garvey poster in his room at the age of just 4 back in the 1970s, when Garvey was an all-star first baseman for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Garvey was the baseball hero of his time in Southern California, and that poster had him at bat, a familiar if not famous stance that often meant good things were about to happen. He played on four Dodgers World Series teams and one more with the San Diego Padres.

He was the sort of childhood icon that baseball fans grow up revering. As adults, those fans still tend to view their heroes through a veiled lens that only sees memories from an innocent time.

Strickland, now 54, met Garvey a year ago at a fundraiser at Huntington Beach’s Huntington Club, finally shaking hands with the man forever etched in his memory in the sort of comforting recollection that only grows more tender with time.

Garvey told Strickland that day that he was considering running for the U.S. Senate.

“Whoa,’’ Strickland said.

“I said, if you decide to do it,” he said, without hesitation. “Count me in.”

Strickland’s affection for Garvey illustrates the unique potential of this political neophyte. Despite years of financial turmoil, and a post-baseball life largely outside the public view, Garvey remained political gold to Southern California baseball fans — particularly the Republican ones.

“My general feeling is that Steve Garvey’s history and support transcends politics and political parties,” said Sacramento-based Republican consultant Duane Dichiara.

Few Californians, though, know who Steve Garvey is now. What is his occupation? What has he been up to since leaving baseball at the end of the 1987 season?

Garvey remains an enigma, a puzzle whose pieces don’t yet fit together. His speeches and campaign website promise collegiality and general solutions to vexing problems. In this winter’s debates, he stayed away from offering any strong ideology.

His campaign and top strategist did not respond to requests for comment by The Bee about his campaign.

So who is Steve Garvey today, and why is he running?

The quiet campaign

At roughly the same time he met Strickland last April, Garvey was reaching out to Los Angeles-based Republican consultant Andy Gharakhani to have detailed conversations about a possible run, according to another GOP consultant, Matt Rexroad.

The effort quietly expanded as Garvey and Gharakhani spoke with influential Republicans, hosting private dinners in Beverly Hills and elsewhere in Southern California to discuss a race.

Those consulted liked the idea, and though Garvey had never sought public office, he had eyed a Senate bid since his days as a player. Now it all came together quickly.

“As a well known ballplayer from L.A., he has some degree of star power. And Californians from both parties always get goo-goo-eyed over stars, whether they are from Hollywood or the sports world,” said Dave Gilliard, another California Republican campaign consultant

Today, Garvey is in a head-to-head race with Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Burbank, for a Senate seat.

Garvey is far behind Schiff in the latest Berkeley-IGS poll, and trails Schiff in campaign cash on hand, according to reports through March 31. But Garvey backers point to exit polls from the March 5 primary showing the Republican as the choice of 41% of independents, who made up more than one-third of the vote. Schiff had 22%

Garvey also performed better than former President Donald Trump, receiving 2.32 million primary votes in the race for a full Senate term, compared with the 1.95 million Trump received in the March presidential primary.

Republicans need a candidate

Republicans last year were eager to find a credible statewide candidate. With the U.S. Senate seat up in a presidential election year — a year that often means higher turnout among GOP voters and independents — the party saw an opening.

A strong Senate contender could help California’s GOP brand, which has lagged badly, with no Republican winning statewide office since 2006.

Since 1992, both California senators have been Democrats. And of the state’s 52 House members today, just 11 are Republican.

“If you’re the Republican Party, you want someone who can hold up the banner and bring out votes for House seats and other local races,” said Jon Fleischman, former California GOP executive director.

Republicans, though, at first lacked a prominent Senate candidate who would instantly be known and, in many circles, even loved.

They wanted someone who could not only run a strong race but motivate Republican voters — and the state’s sizable bloc of independents —to come out and vote for GOP candidates.

Enter Garvey.

“Don’t underestimate how difficult it is to generate pride in the party if you don’t have a credible candidate in the statewide Senate race,” said Fleischman. “Here’s somebody who’s already very well known.”

The newest celebrity

To political strategists, Garvey had potential as the latest in a line of California celebrities with no need to explain who they were to a constituency smitten with fond memories of their triumphs.

Garvey, the thinking went, could be another George Murphy, the song-and-dance man who won a Senate seat in 1964, or Ronald Reagan, the TV and movie star first elected governor in 1966 and president in 1980. Or more recently, Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Terminator turned governor, the last Republican to win statewide in California.

The private discussions during the spring of 2023 went well for Garvey.

“People have been talking about Steve Garvey seeking political office for decades,” Rexroad said.

He recalled that people had been talking about a Garvey political run for decades. In March of 2023, Rexroad said, the former Dodger reached out to Gharakhani to have a more detailed conversation about a possible bid in 2024.

In August, Rexroad said he “met with Garvey and Andy on a ridiculously hot day in Palm Springs. “ They talked for months about the race, about “the pros and cons of the campaign....After discussing unique ways to accomplish our goals, and a path to victory, he decided to enter the race for Senate.”

Top state Republicans met at private dinners with the Garvey team. Shawn Steel, the state’s Republican national committeeman, and his wife, Michelle, an Orange County congresswoman, had dinner with Garvey and Gharakhani at the posh Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills last May.

Steel recalled how he grew up listening to Dodger games on his transistor radio in the ‘60s, and he had seen Garvey at the congresswoman’s April fundraiser at the Pacific Club in Newport Beach.

Timothy O’Reilly, the Los Angeles County GOP chairman, also had dinner with the Garveys last spring. He saw all the traits that could make Garvey an instantly credible, likable candidate.

“I found Mr. Garvey to be a charming and sincere man who feels deep gratitude to the people of California. As a lifelong Republican, he was concerned that we were losing our beautiful Golden State, the one that made his life possible, to the destructive policies of radical Democrats,” O’Reilly recalled.

Garvey would be a Republican candidate whose political identity was tough to pin down, an important asset in deep blue California.

In June, when he announced he was exploring the race, and in October, when he formally entered with a one minute, 11 second video, Garvey presented himself as a team player unencumbered by partisan politics.

Half the video recalls his baseball days, with Garvey talking about how he “never played for Democrats or Republicans or independents. I played for all of you.”

He never says he’s a Republican. He pledges a “common sense campaign.”

Why the Senate?

The U.S. Senate is often a landing spot for celebrities seeking a national microphone. Unlike races for local offices or even the U.S. House, candidates don’t need to show their deep knowledge of local affairs or rely on long-standing local friendships.

The current Senate has members who largely rode their celebrity into office, such as former Auburn football coach Tommy Tuberville, bestselling author J.D. Vance and astronaut Mark Kelly.

Garvey was conservative, but not doctrinaire, and liked the idea of being a leader who brought people together. As far back as 1981, in Playboy interview, he cited President Gerald Ford as a model at building consensus, and hinted at interest in the Senate.

“Either I start at the U.S. Senate or nothing. Because I wouldn’t have time to work my way up,” he told Playboy.

Garvey also had the requisite image at the time. He was a family man, a nice guy, an easy talker who always had time for charities and autographs. The “epitome of the Southern California cultural icon in baseball spikes,” said the Society for American Baseball Research.

Garvey also understood celebrity outside of sports. His nickname was Mr. Clean. He appeared on the daytime soaps “The Young and the Restless” and “The Bold and the Beautiful,” the sitcom“Just Shoot Me” and the lifeguard series “Baywatch.” He did ads for Chevrolet, Jockey Underwear and Geritol, and gave baseball tips on Post Raisin Bran boxes.

He had been an avid Reagan supporter and introduced him at a San Diego rally in 1984. After Reagan’s speech, Garvey gave him a Padres jacket. Later, he campaigned for President George H. W. Bush.

Since then, he hasn’t been visible in politics. He said at the January Senate debate that he voted for Trump twice but wouldn’t say who he’s picking in November.

Where has he been?

Garvey’s candidacy comes with a broad, often tough-to-answer question: Where has he been for the last 37 years, since he stopped playing?

His address as of last year was listed as a 5,000-square-foot home in Palm Desert valued on Redfin at about $2.6 million. He has occasionally been in the news because of financial and personal controversies. His supposed storybook marriage to Cyndy Garvey fell apart in the late 1980s.

Garvey fathered two children out of wedlock in 1989, and married a third woman that year. He became a favorite joke for comedians. A T-shirt read: “Steve Garvey is not my Padre.”

“Some people have a midlife crisis,” he told Sports Illustrated’s Rick Reilly in 1989. “I had a midlife disaster.”

His financial troubles made the news. In 1996, Garvey said in a legal declaration that he was the victim of a “financial disaster” in connection with poor investments and mounting debt. In 2000, he and the Garvey Management Group, owned by his wife, Candace, were sued by the Federal Trade Commission.

The FTC alleged the couple were making false claims about a weight-loss product they touted in infomercials. Four years later, a federal appeals court found them not liable for the claim, saying they had no actual knowledge that their claims were false.

In 2003, Sports Business Journal ran a story headlined “Steve Garvey’s Public Exile.”

It found that for Garvey, “There’s no political office, no high-profile endorsements, not even a position as visible as publisher of Sport, which he held briefly in the mid-1990s before the magazine folded, or as a radio talk show host, a role he played for a time in San Diego.”

The problems continued. The Los Angeles Times reported in 2006 that he routinely didn’t pay bills. He incurred tax debts in 2011 that still have not been paid.

Is he paying his taxes?

The Bee reported in March that Garvey owed between $350,000 and $750,000 in unpaid state and federal taxes. Garvey said he’s working with the Internal Revenue Service and accountants to “resolve the debt by the end of the year.”

His latest campaign disclosure form said he’s incurred between $250,001 and $500,000 in federal tax liability since 2011, and another $100,001 to $250,000 in back taxes owed to the California state government, also since 2011. He owes 8% interest on the balance due.

Garvey also has a long history of having liens filed against him. The IRS and state of California have filed more than 30 liens against Garvey since 1991, totaling about $4 million, records from local counties show. At times his wife, Candace, is also named.

The IRS and State Franchise Board use liens, the right to collect someone’s property to pay off a debt, when someone is delinquent on taxes.

Liens often involve housing, and taxpayers can still live in the home if there’s a lien. The IRS usually has 10 years to collect an unpaid tax, but it’s not uncommon for a lien to be extended.

How Garvey settled some liens and is dealing with others is unclear. Liens can be released when someone pays his taxes or reaches an agreement.

Garvey’s lien history includes:

▪ $2 million in released liens. These liens were dropped in 1998 as the tax debt was settled. The liens had been imposed in Los Angeles County, where Garvey lived at the time. The largest, filed in 1995, was for more than $960,000. Another, filed in 1994, involved $956,080.

▪ Riverside County liens. Most of the actions have been filed in the county where Garvey and his wife have recently had a Palm Desert home. Among the largest is a lien filed against the Garveys in 2012 for $425,508 by the IRS.

▪ Recent liens. A year ago, the state filed a lien against Steve Garvey for $28,461 in Riverside County. The more recent IRS filings have been against Steve and Candace Garvey in 2018 for $324,627 in Riverside, Los Angeles and Orange Counties.

Garvey’s campaign did not respond to The Bee’s request for comment about the liens.

How does he make a living?

Garvey has made a living as a motivational speaker, local radio show host, celebrity endorser, sports commentator and founder of a marketing firm. At one point, his speaking fee was listed as $25,000.

His February 2024 federal disclosure form, required of all Senate candidates, shows he has income from four sources.

They include GEP Talent of Burbank, Fox News, the Topps Company and IPG DXTRA of Omaha. He lists Topps and IPG DXTRA as paying him for memorabilia signings and “corporate entertainment.”

IPX DXTRA said it brings “experts in PR, branding, digital, experiential, influencer and entertainment together to deliver creative, meaningful and stand-out answers.”

Garvey reported “self-employment income” of $22,688 from Topps, $93,700 from IPG DXTRA, $5,000 from Fox and $486 from GEP.

The IPG DXTRA payment “was made on behalf of a client of ours for an appearance Mr. Garvey made at a sponsored sports event. At no time was Mr. Garvey an employee of our company,” a company statement said. Because of confidentiality agreements with clients and those they work with, it could provide no further details..

What’s Garvey thinking?

Garvey has rarely campaigned and, in debates and appearances, sticks to lofty, general promises that usually defy any firm ideology.

On his campaign website, he offers his views on a series of issues. Most of his discussion involves learning more.

“Let’s find out what’s working and what’s not by auditing the money that has been spent on this crisis so far,” he says in the section on homelessness. On crime, he promises to “work towards building strong partnerships between law enforcement and communities.”

He wants secure borders, as well as a plan “to develop practical pathways to citizenship for those who positively contribute to our society.”

The site’s “Steve’s Vision” section makes no mention of Trump or the Republican Party. The one consistent theme is baseball. The campaign’s logo features a picture of him as a baseball player. The SuperPAC that raises big money to help him (while not officially connected to his campaign) is called “Strike Out Schiff.”

Recently, Garvey has been actively tweeting, though he offers few concrete solutions to issues he raises.

“Unaffordable gas prices are hurting Californians’ quality of life every day. I see people putting $10 in at the pump instead of 10 gallons. Join my campaign if you believe California deserves better,” he said in a post on X April 5.

Unaffordable gas prices are hurting Californians’ quality of life every day. I see people putting $10 in at the pump instead of 10 gallons. Join my campaign if you believe California deserves better. pic.twitter.com/jywGh6Y2na

— Steve Garvey (@SteveyGarvey6) April 6, 2024

“I am driven by a commitment to every Californian’s dream for a better tomorrow. Let’s move onward together,” he said in another X post.

His speeches are filled with baseball references, stretched to show that he’s not tied to ideology. Just the nice guy who Californians cheered and celebrated on the ballfield.

As he secured a place on the November ballot following the March primary, he told supporters, “I played for all the fans, and tonight I’m running for all the people.”

Give him an issue and his answer often lasts as long as it takes a fastball to cross home plate. He tweets often about how he wants to ease homelessness, and when he visited Sacramento in January and met with unhoused residents, he was asked how as a senator he would seek to do so.

“In a federal position like U.S. Senate you can get those answers. On that stage, on that platform, I’ll get answers,” Garvey said.

He had nothing specific.