Pa. court strikes down a key climate program, but environmentalists expect an appeal

Spotlight PA is an independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit newsroom producing investigative and public-service journalism that holds power to account and drives positive change in Pennsylvania. Sign up for our free newsletters.

HARRISBURG — Two Wednesday court decisions striking down Pennsylvania’s participation in an interstate program to reduce carbon emissions have set the stage for the matter to advance to the state’s highest court.

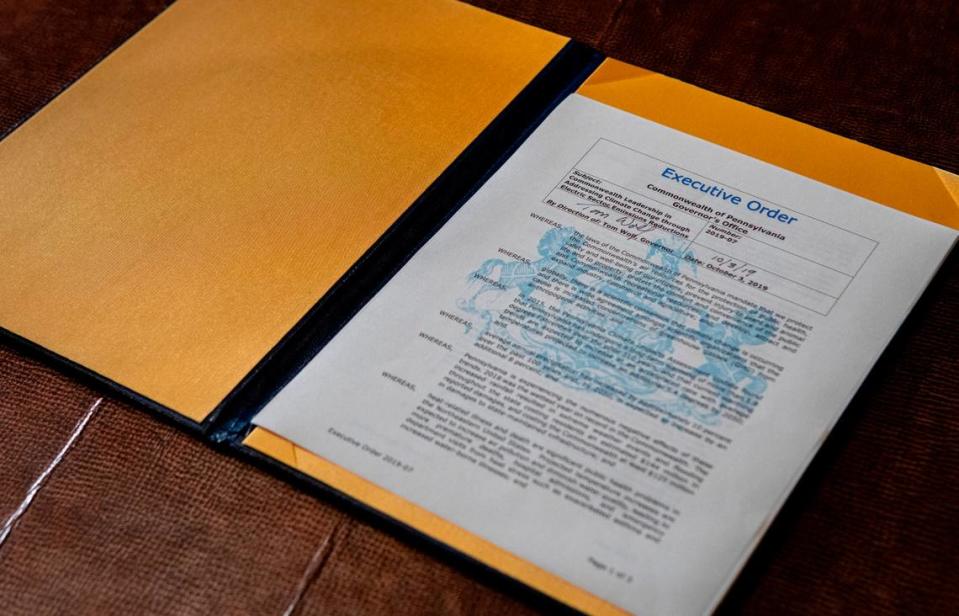

The pair of Commonwealth Court rulings found that former Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s attempt to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, commonly known as RGGI, was an overstep in executive power. States in the initiative agree to cap the amount of carbon that producers within their borders can release. This cap lowers over time, guaranteeing a decrease in emissions. States can each sell a certain number of emission allowances that fall under the cap, which companies must purchase in order to emit any carbon. The proceeds of these sales go to the states.

At the heart of the two cases is whether this regulation on energy producers constitutes a tax or a licensing fee. Critics argue it’s a tax and that only the legislature has the power to levy taxes. Because Wolf joined RGGI through an executive order without input from the legislature, opponents say this makes the program unconstitutional.

Supporters of the program argue the state is able to regulate energy companies under the federal Clean Air Act and say imposing an emission limit on energy companies does not constitute a tax, but a fee, which the governor doesn’t need legislative authority to impose.

In one of the two cases Commonwealth Court considered, the plaintiffs included a group of energy companies, unions, and other energy interests. That case focuses on the legal difference between a tax and a fee, and considers which category RGGI costs should fall under.

In the other case, state legislative leaders are arguing the Wolf administration overstepped its power by trying to implement RGGI without their approval. Because this argument centers on the legislature’s power to issue taxes, it would mostly become moot if a higher court finds that RGGI costs are actually a fee.

Pennsylvania first joined RGGI in 2019, but the move was quickly met with lawsuits from state Senate Republicans and energy interests. In 2022, Commonwealth Court issued an injunction that prevented Pennsylvania from moving forward with RGGI. This included a bar on the state participating in auctions in which companies buy and sell credits that allow them to emit carbon, a central part of the program.

Following the court’s decisions, state Senate Majority Leader Joe Pittman, R-Indiana, said in a statement that Pennsylvania’s entrance into RGGI “may only be achieved through legislation duly enacted by the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

“Gov. Wolf’s decision in 2019 to unilaterally force Pennsylvania to join RGGI was a failed, harmful, and unconstitutional policy,” Pittman said.

Environmental advocates and other RGGI supporters say they were not surprised by the latest rulings.

“The decisions are flawed, and, frankly, went about as expected,” said attorney Robert Routh of the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. “We look forward to the Governor appealing this decision.”

A spokesperson for Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro said the administration is “carefully reviewing” the decisions, and did not specify whether it plans to pursue an appeal.

“This decision is solely focused on the narrow question of whether this policy put in place by the prior administration constitutes a tax or a fee,” the spokesperson wrote.

Shapiro’s position on RGGI is far less clear-cut than Wolf’s was.

The first-year governor has been unwilling to commit to a position on the program. He formed a work group to determine whether RGGI would “protect and create energy jobs”; “take real action to address climate change”; and “ensure reliable, affordable power for consumers in the long-term.”

Emails obtained by Spotlight PA through open records requests show that from the start of Shapiro’s administration, top aides were searching for “RGGI alternatives.”

In a recent memo outlining its findings, Shapiro’s work group did not come to an unanimous decision on RGGI but said it broadly supported a cap-and-trade program of some sort.

Pennsylvania law allows parties 30 days to file appeals to the state Supreme Court.

BEFORE YOU GO… If you learned something from this article, pay it forward and contribute to Spotlight PA at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.